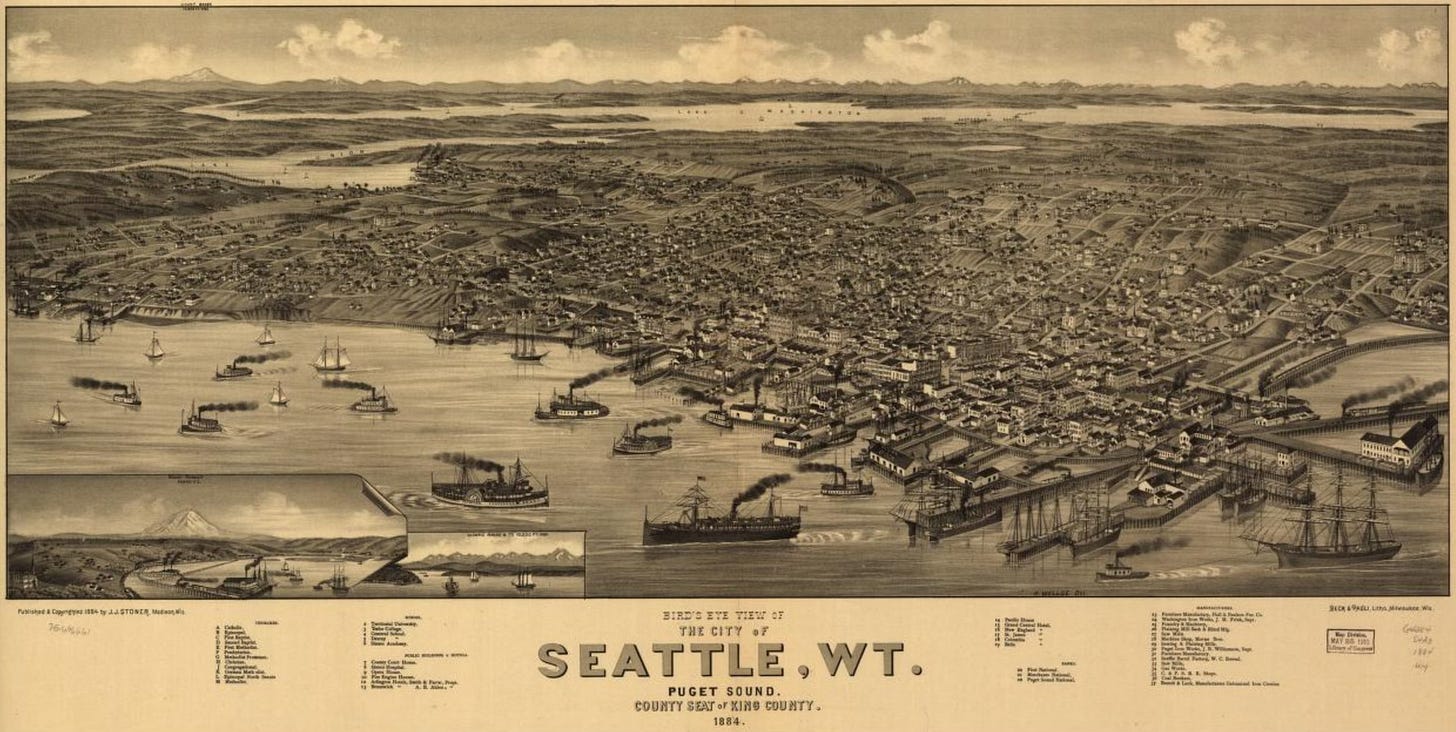

On July 14, 1884, a short article appeared in the Seattle Daily Post-Intelligencer. It noted that artist H. Wellge had just completed “the finest view of Seattle ever taken.” The image was of the bird’s-eye character, measured 14 inches wide and 33 inches long, and would cost $3 apiece, or 12 for 20 bucks. “It will be a splendid thing to send abroad to advertise the town.” Bird’s Eye View of the City of Seattle, WT would be one of more than 150 panoramic bird’s eye views that German-born Henry Wellge (1850-1917) made from Florida to Yellowstone National Park to Seattle.

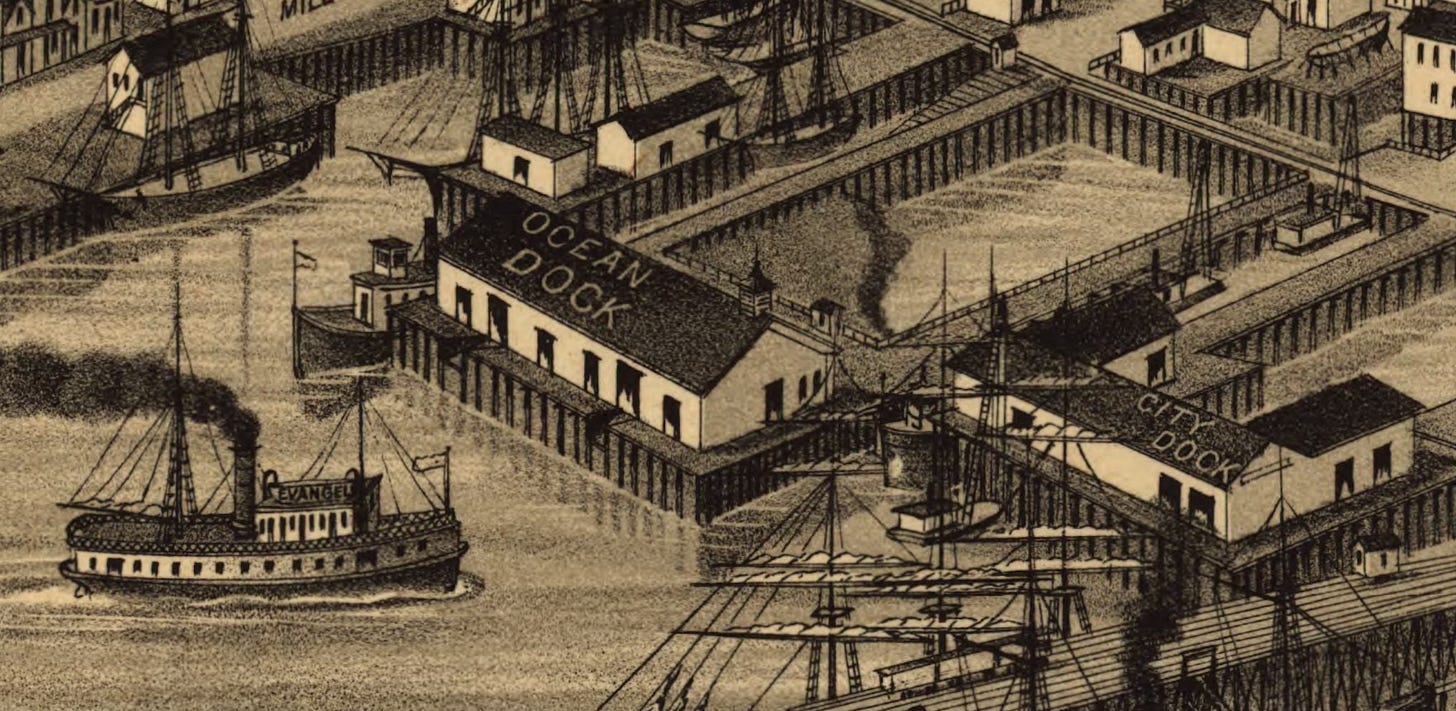

In Wellge’s illustration, Seattle is in full commercial bloom as the rising city of Puget Sound. More than 36 ships—steamers, paddle wheelers, one-, two-, and three-masted sailing vessels, and no canoes—vie for space on Elliott Bay. They include the 336-foot, iron-hulled Queen of the Pacific, which could hold 300 passengers; the 270-foot side-wheeler Olympian, which crashed in the Straits of Magellan, where its remains could be seen until 1980; the steamer Evangel: envisioned as a ship to spread the gospel (a little girl dropped religious tracts into the water as it was launched), it soon blew up and killed three men, was repaired, but then sank, for good; and the T. F. Oakes, a three-masted clipper jinxed by bad luck (in 1897, after an epic trip when the ship had been given up, it was towed into New York with a scurvy-ridden crew).

Those ships, plus two railroad lines (one of which is the Northern Pacific), serve the busy waterfront. Six years after the previous bird’s eye I described, wharves, docks, and piers have continued their push into Elliott Bay and obliterated the historic shoreline. Whellge shows furniture manufacturers, a barrel factory, coal bunkers, machine shops, two iron works, and at least six sawmills. One dock, Ocean Dock, extends far enough into the bay to have encompassed Ballast Island, the artificial island that had become a sort of safe haven for Native people, one of the few places where they were tolerated in Seattle.

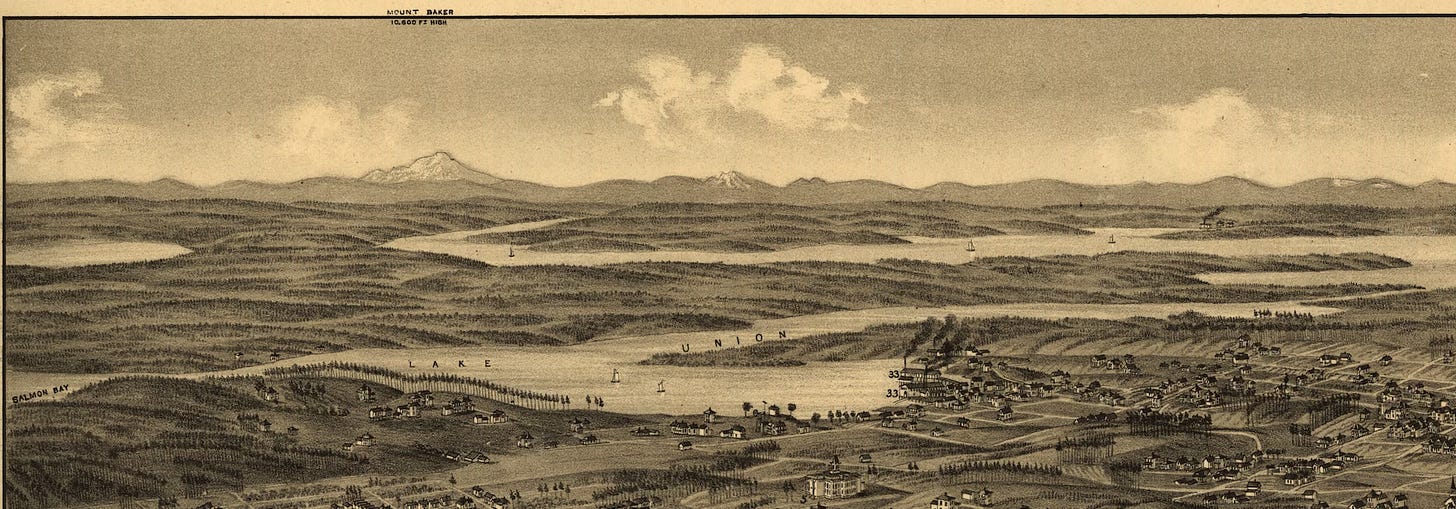

In addition, Wellge shows how a few people have begun to populate the east side of Lake Washington. Those who wanted to reach their homes would catch a ferry at what is now Madison Park and was then the “Laurel Shade” home of Elizabeth and John McGilvra. Access to Laurel Shade was by a wagon road, which inexplicably curves in Wellge’s drawing but actually was straight; the route, now Madison Street, still exists and is the only road directly linking Lake Washington and Elliott Bay.

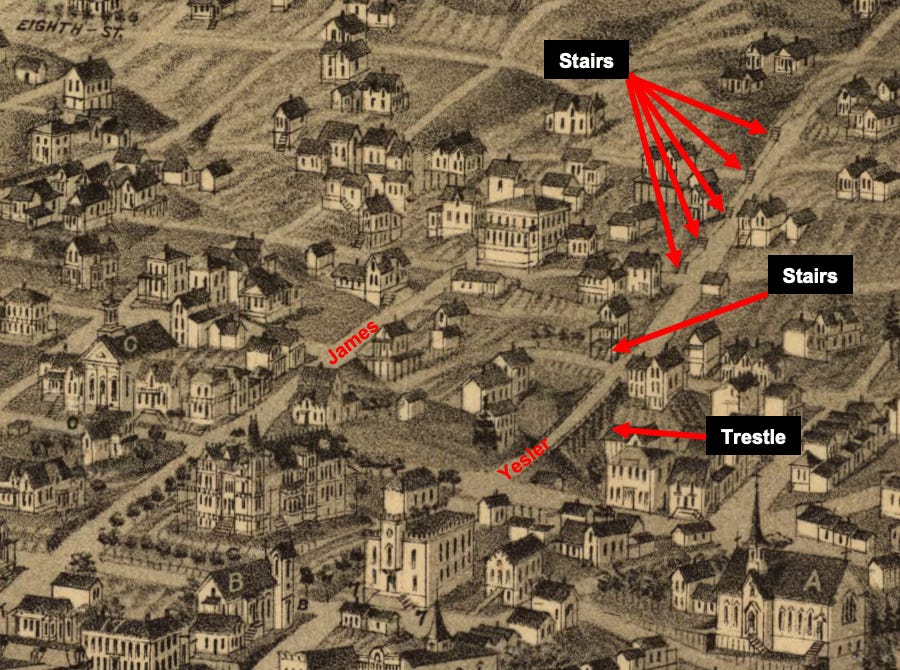

From a topographic point of view, Wellge is far more accurate than Eli Sheldon in 1878. The best place to see this on Yesler Street (aka Skid Road) as it rises east from the waterfront. Note how the road crosses on a trestle over a valley then climbs the slope. The road is so steep that it requires stairs, as Wellge shows. You can also see where several houses include entrance stairways, a sure sign of vertical relief.

He also includes another unexpected feature, a lake located perhaps around 17th Avenue and Denny or Howell streets. It’s hard to place it but it appears to be on Capitol Hill, where no lake of this kind has been known. In contrast, Wellge removed Foster Island, leaving Union Bay featureless.

By the time of Wellge’s drawing, industries had started to spread north to Lake Union though Seattle’s original railroad, the Seattle Coal and Transportation, no longer existed. Most prominently, smoke spews out of David Denny’s Western Mill Company, which sits on land where the Museum of History and Industry is now located. With the mill running out of trees to harvest on the surrounding hills (though there’s a curiously well-ordered stand on west side of the lake), Denny and other investors would form the Lake Washington Improvement Company. Their plan: connect Lake Union with Lake Washington in order to exploit the virgin forests to the east.

To do so, the LWIC worked with the Wa Chong construction company to cut a canal between the lakes, as well as between Lake Union and Salmon Bay. Wellge included both connections, though he doesn’t show the locks at the canal linking the lakes; it’s located roughly where SR-520 is, a few hundred yards south of the modern Montlake Cut. The canals were probably not yet completed when Wellge made his panorama but would soon be.

As I look at this map, Seattle appears to be on the verge of booming but then I focus on the background. The forest begins just east of about what would soon become Capitol Hill, and north of Lake Union. Trees spread for miles across a rolling topography that ends at the jagged horizon where massive peaks (Baker, perhaps Shukson, Whitehorse, Three Fingers, Pilchuck, Glacier and others, plus Rainer in an inset), rise to snowcapped summits. Despite the city’s rapid growth and fierce ambition, it is still just a speck, barely chipped into a rugged wilderness.

This dichotomy is one of the reasons I love noodling around in these bird’s eye maps. They provide an unrivaled and truly imaginative way to time travel back to the early days of my hometown. Of course, I know what happens next but it’s still fascinating to see how that story develops.

Radio Free Magnuson Park - I am excited to announce that I now have a second podcast. Every Wednesday at noon, SPACE 101.1FM will air another segment from the Street Smart Naturalist. In these episodes I will be reading older newsletters, which I wrote before I started reading them as I do now. And, one of the great things about these new ones is that they are produced, so the sound quality is better. Hope you enjoy them. The first episode is Erratic Behavior.

Special Offer for those who like to listen to books: For the first four people who get a paid yearly subscription to my newsletter, I can give you free access to the audio book version of Wild in Seattle.

Share this post