The narrow band between high and low tide is Puget Sound’s most protean ecosystem, where the rhythms of existence fluctuate with the twice-daily expansion and contraction of our inland sea. For thousands of years, those pulses of water dictated life for the Sound’s human inhabitants. Where people lived, how they traveled, and when they could find food all depended on knowing the tides and how they affected the movement and location of water, plants, and animals.

Today, understanding the tidal cycle of the Sound has little relevance to most residents’ lives. We no longer worry much about the phase of the moon or how the tide might affect our next meal. This lack of awareness of the tidal rhythms is neither good nor bad: it’s simply the reality of our lives and a reflection of our overall disconnect from the natural world around us.

Hoping to remedy my disconnect, at least in a minimal way, I decided to watch a tidal exchange at Seattle’s Discovery Park. On August 10, 2017, I reached the beach at 6:30 a.m., when the tide had been ebbing for three hours. I established my base for the day at a driftwood tree trunk perfect for leaning against. A dozen feet away, beyond a sloped cobble and sand beach, waves approached the shore so gradually and quietly that they seemed reluctant to arrive. Beyond, no feature broke the smooth surface.

The water continued to recede from the sloped beach out onto a terrace. By 7:00 a.m., the top of a boulder poked above the surface about sixty-five yards offshore. Closer in, three ends of a stump had breached, and within another hour, the water had retreated enough to expose more than a dozen boulders the size of a doghouse or larger, as well as seaweed-strewn fingers of cobbles and expanses of rippled sand. Farther out in the water, a steady stream of kelp moved north, carried by the ebbing current.

As the water retreated, I periodically abandoned my tree trunk to explore the world so recently revealed: barnacle-covered boulders and worm-covered barnacles; horse clam siphons and moon snail casings; crabs and crab tracks; anemones, logs, eelgrass, and kelp; ripple marks, pools, and channels; red algae and white bird poop; abandoned pier pilings and critter-filled tires; tube-worm towers and squiggly worm castings; Great Blue Herons with fish in their bills and gulls with clams in their bills; squadrons of black-capped Caspian Terns and a lone Bald Eagle harassed by gulls; and a variety of holes in the sand that hinted at another hidden world below.

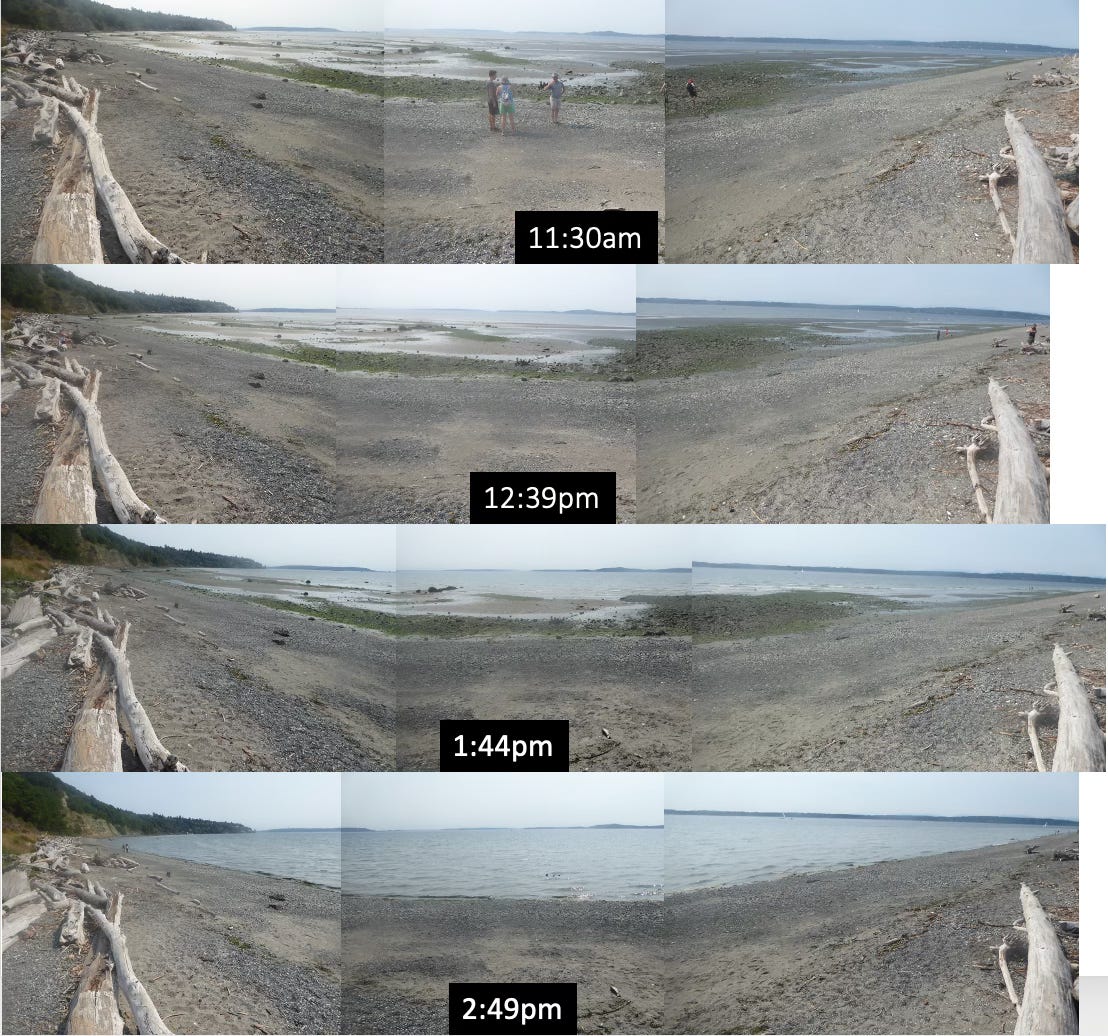

At the bottom of the tide, at 10:34 a.m., the beach was more than a third of a mile wide. I observed only minimal change over the next hour, during what is known as slack water. Then the water began to advance at increasing speed, moving fastest between 1:30 and 2:00. During this period, I walked out to the waterline, stopped, and watched as the water swelled toward shore. Twenty minutes later, the water was close to my knees, and the waterline had advanced more than one hundred feet. After another thirty minutes or so, the waterline was almost where it had been when I arrived eight hours earlier.

Watching that surge was humbling and exciting, fully revealing the tidal pulses that most Puget Sound residents, me included, fail to notice every day. Every twelve hours the Sound inhales and exhales, covering and uncovering a beautiful, evanescent world at the intersection of land and water.

This newsletter originally appeared in March 2021 and comes from Homewaters: A Human and Natural History of Puget Sound.

Word of the week - Protean - Variable in form, changing or unpredictable. Protean comes from Proteus, a sea-god, the son of Oceanus and Tethys, who could assume various shapes at will. Apparently he did this because he had the gift and prophecy and shape-shifted to avoid all those who sought him out.

Share this post