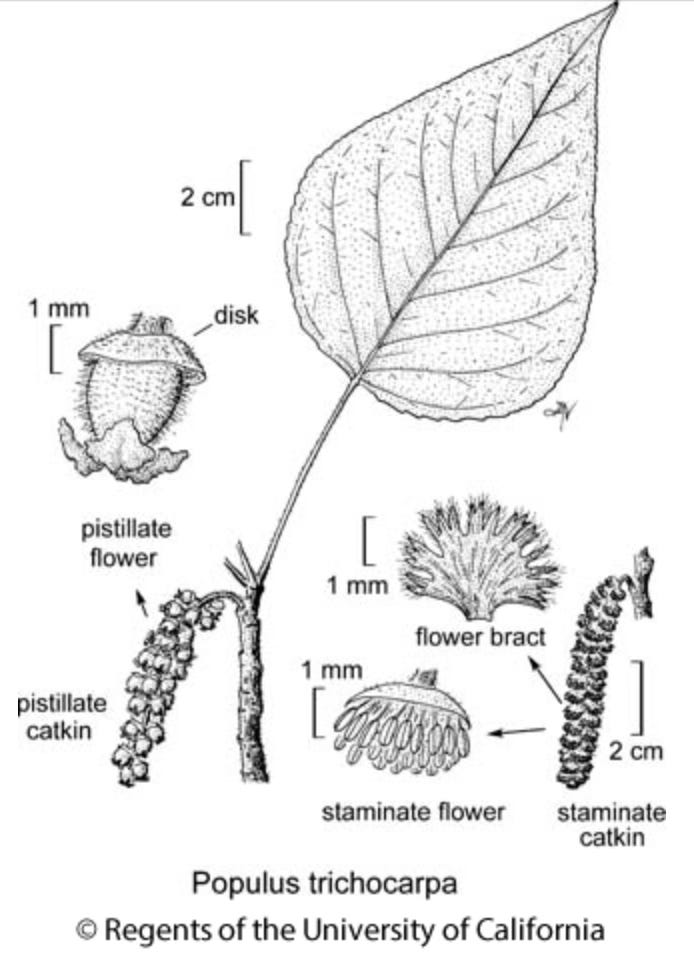

Tis that time of year when cotton starts to snow the landscape. I always enjoy this annual falling of little white clusters out of the sky, particularly since we see so little real snow falling in Seattle. Neither cotton nor snow, the white “flakes” come from our local cottonwood, the black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa. The specific epithet provides a hint to the plant’s legendary, or notorious for some, feature, as trichocarpa means “hairy seed,” from the Greek thrix, a hair, and karpos, fruit.

The female plants generate the snowstorms, from their seedpods, about the size of a pea and clustered like grapes. When ripe, the pods release gazillions of minute seeds with their silky tufts. (One time while riding with my friend Scott, the cotton was so dense on the trail that it felt like we had magically time traveled to winter and riding on fresh snow.) Providing buoyancy, the hairs allow the seeds to sail the wind, for miles in the right conditions. With a viability of just days to weeks, few germinate and even fewer survive to reproduce themselves, which is why the plants have evolved to produce their seed blizzards.

Not everyone cottons on to these cottonwood seed storms. They dislike how the seeds clog filters, get in their hair or in their throat, and stick to screens. I get these concerns but still am glad that cottonwoods grace our environment and would rather celebrate than bemoan.

When the seeds do succeed, they produce a stately, magnificent tree, the biggest of which can shoot straight up for 200 feet, though 100 to 125 feet is more common. Such monster trees have six- to ten-foot-wide bases that are truly spectacular. The furrowed bark, and tendency of the trees to lose limbs easily, creates splendid habitat for a variety of birds, mammals, insects, and arachnids. Studies have found dozens of animals that exploit the many cavities that riddle cottonwoods ranging from bats to woodpeckers to black bears. Ospreys and Bald Eagles further exploit the platforms that form from broken limbs.

Cottonwoods are also well-known for their predilection for reproducing from their stumps, which is particularly effective for a tree that often topples in wind and flood events. But they can generate new plants, too, when shedding, or abscissioning, twigs with leaves. Botanists refer to this process of abscission as cladoptosis (from the Greek for young branch and ptosis, or falling) and have found that it may enable cottonwoods to quickly colonize and stabilize sandbars.

All members of the gang of poplars (another name for these trees) are trees of the riparian environment. Because of their aqua-phillic ways, cottonwoods were long seen as a reliable indicator of water. This asset was especially important for travelers heading west in the middle 1800s, who often were in search of water. With their wonderful and wide and leafy overstory, cottonwoods also provided a lovely, shady location to avail oneself of.

Here in the land of big conifers that dwarf even the tallest black cottonwood, the snow producers have long been overlooked. I know that I didn’t even realize they grew here until many years ago when I was working on a book chapter about what Seattle looked like botanically in 1850. As I was reading the notes of the region’s first land and plant surveyors, who worked for the General Land Office’s cadastral survey between 1855 and 1862, I kept coming across the name of a plant I had never encountered: Balm of Gilead. (The “original” Balm of Gilead originally referred to a Biblical medicinal unguent and now refers to any “universal cure.”)

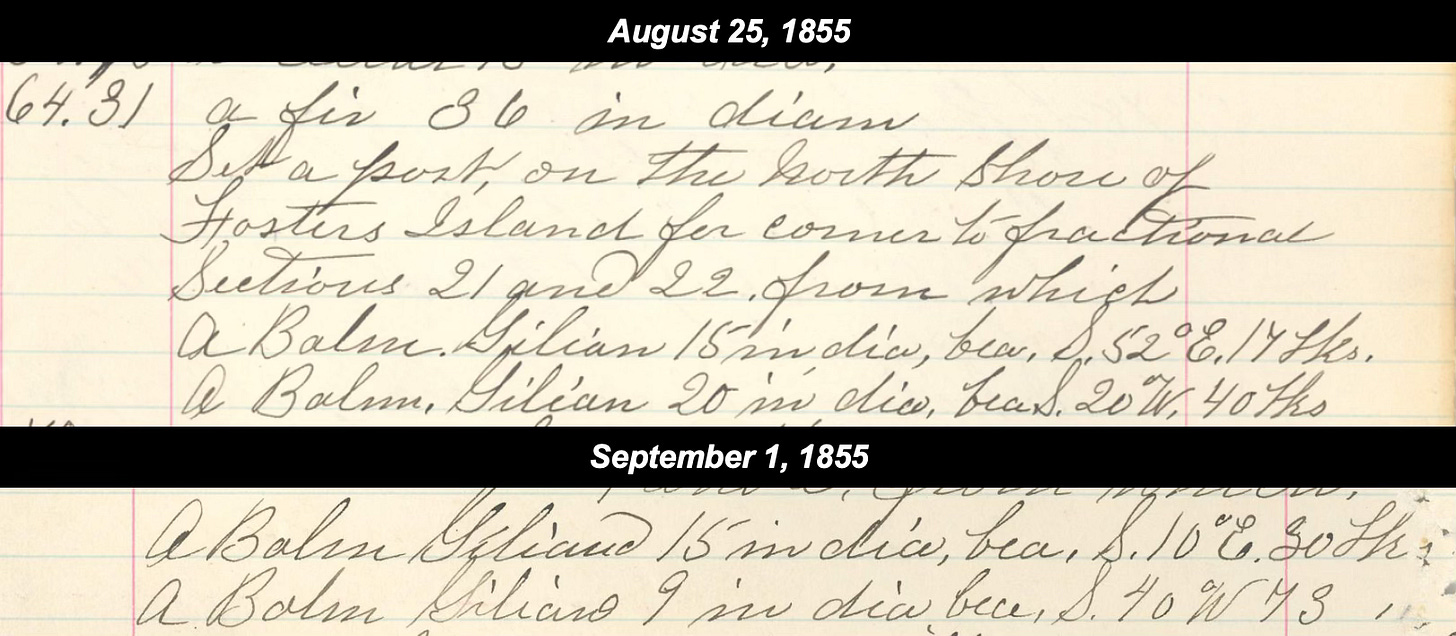

For example, on August 25, 1855, along the shore of Lake Washington, at Fosters Island, surveyors David Phillips and Willam A. Stricker noted two Balm of Gilead (they were inconsistent in their spelling; here they wrote Balm Gilian). Six days later they noted more “Balm Gileads” along Lake Washington, near present day Denny Blaine Park. In Raymond Larson’s master’s thesis, The Flora of Seattle in 1850, he wrote that Populus trichocarpa was of moderate abundance along riparian areas and that evidence for the trees could be found, in addition to the GLO notes, in settler’s accounts and herbarium records.

Probably the most famous regional Balm of Gilead was located in Vancouver, Washington. Legend holds that Lewis and Clark tied their canoe to it in 1805; that nineteen years later, the Hudson’s Bay Company established their first trading post under the shadow of the tree; that an HBC employee drove a copper railroad spike into the tree, which served as the zero point for all subsequent surveys; and that one Amos Short established the town of Vancouver, with a layout “Beginning at an old Balm of Gilead tree on the bank of the Columbia River.” That witness tree passed into true infamy when, at 3:45 pm on a Sunday afternoon, it “toppled into the Columbia River, where it now lies, all hope of ever preserving it having vanished the moment that it fell,” according to The Columbian of June 28, 1909.

We may no longer refer to these stately trees as Balm of Gilead but I still think of them as bestowing universal cure. With Seattle’s weather heating up again—we’re supposed to reach the upper 70s today….heavens to Betsy!—I am looking forward to the continued rain of cottonwood’s snowy seeds. They at least give me the impression of coolness amid the stifling heat we have to endure.

Special deal on Wild in Seattle - If you buy one from me, I will include a lovely set of stickers by Elizabeth Person of animals from the book. Here’s a link to purchase the book.

If you happen to be in Winthrop on June 14, I will be there, in conversation with the esteemed naturalist and Methow Naturalist editor, Dana Visali, at the Winthrop LitFest.

Thursday, June 12, Third Place Books, Lake Forest Park - I am truly honored and humbled to be interviewing Robert Macfarlane about his newest book Is a River Alive? It’s quite stunning, revelatory, and provocative. I am very much looking forward to the opportunity to chat with him. Reservation required.

And, again, here’s a link to my Wednesday show on Space 101.5 FM. This one is about the perennial whole in the ground building site across the street from City Hall in downtown Seattle and lovely life that has found purchase there.

Share this post