We recently spent some time in Boston, where Marjorie and I lived between 1996 and 1998. It was a trying time then. We had moved from Moab, Utah, a geological paradise, to a place where the sum total of my geological knowledge was Plymouth Rock. For the first many months I had no connections to the place, to the natural world that inspired and grounded me, as it had done in Utah.

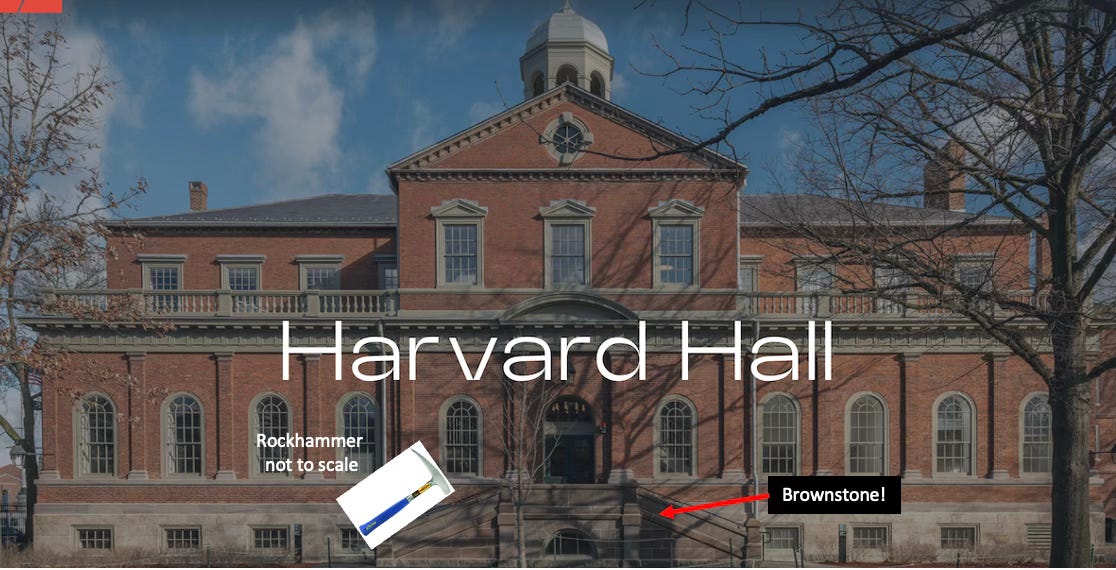

But then one day I was on the Harvard campus looking at Harvard Hall, built in 1766. At its base was a rock that Bostonians and New Yorkers call brownstone, oddly in reference to its color, which seemed more reddish than brown to me. Not having a rock hammer with me, and figuring that those august Harvardians might not appreciate that I was simply doing what geologists do, that is whack rocks off bigger rocks to make smaller ones to inspect, I simply rubbed my hand on the sandstone. In my half-gowpen, grains of red sand accumulated.

It was then that I realized that an easterner’s brownstone was a westerner’s red rock. Both are sandstone with small amounts of iron that has oxidized, or rusted, bestowing a reddish hue. Basically, the grains of sand are like red apples with a red rind around a whitish interior. This epiphany finally gave me a connection to east coast geology. Most of the brownstone used across New England came from quarries in Connecticut composed of a 200-million-year old sandstone that formed during the last significant geological event in the east, the rupture of the supercontinent of Pangea and the opening of the Atlantic Ocean.

Transformed by this knowledge, I began my long love affair with building stone and the geological and cultural stories told by examining the geology of rock used in the urban environment. It is a path I continue to follow, value, and appreciate, which allows me to draw connections between two major aspects of my life, the urban and geologic realms.

Walking around Boston recently reminded me of two other aspects of the town of beans that fascinated me when we live here (pronounced he-ah). The first is the lack of a centering high point, such as Mount Rainier is in Seattle. When we lived in Boston, this was the first time in my adult life I lived somewhere that wasn’t next to a mountain range. I was “nestled at the foot of Pikes Peak,” in college, followed by my nine years in Moab, at the base of the La Sal Mountains, and my on-going, 28-plus years in Seattle. In Boston, the high points were two buildings near each other, the Pru and the John Hancock towers, the latter which topped out at 790 feet.

Tall shafts they are and observable from many places in the relatively flat landscape, the two towers would barely register against the 14,410 foot Mount Rainier, the nearly 13,000 foot La Sals, or 14,115 foot Pikes Peak. Plus, because they were in the middle of city, the towers seemed to move, never anchoring me to direction. That was not an issue for the mountains; visible for hundreds of square miles, they may have popped up at unexpected viewpoints but they were fixed in place, always providing a reference point.

I think that part of my unease in Boston centered on my lack of centering; I never felt like I had my bearings. I was also searching for a way to connect to the city; building stone did provide some of that grounding but never truly enough to satisfy my needs.

Winter brought the other never-before-encountered phenomenon: snow line based on the Interstate and not on elevation. For instance, weather reports regularly described the I-95 and I-495 snow lines. Both roads ring Boston, with I-495 further inland (about 25 to 30 miles versus 10 to 15 miles).

This was nutty and novel to me. What ghost of Robert Moses it be that allowed interstates to control the weather? In Seattle, and much of the west, snow line depends on elevation: the higher the land, the colder the temperature, and thus the snow line. Boston, and many parts of the east, in contrast, follow a different principle. Distance from the coast and the ameliorating influence of the ocean, as well as topography, drives temperature, and thus snow fall. This connection between land and water and snow makes perfect sense (and is partially coincidental with the location of the roads, which tend to follow topography) but still seems odd to my Cascadian soul.

Although I never cottoned to Boston as a home, I am glad that I spent enough time there to begin to appreciate its rhythms of place and some of the natural history that help define The Hub. For me, and I think for many people, connections such as these are essential to their happiness and how they relate to their home place. I am glad that I have now had more than 40 years to learn about and from the amazing and wonderful landscape of Seattle. The stories continue to bring me joy and strengthen my ties to my home place. I hope they do with you as well.

Word of the week - Gowpen - The space formed when you cup your two hands together. The word is of Scottish origin. I learned this term recently in Elif Shafak’s wonderful newsletter, so wanted to try and use it. She writes: “A gowpen of space for independence, freedom, creativity, connectivity, both individuality and humanity… that is where words come from and that is where literature lives, thrives, and works its magic.”

Seattle: A History in Short Stories - This new documentary tells the history of Seattle in short stories, 1 to 3 minutes per subject and will be used primarily in the Washington State History classroom grades 4 and 7. I helped write one of the episodes.

Share this post