As I have been regularly writing, nature is all around us. All one has to do is slow down and pay attention, and the natural world will show her beauty. During our trip to Boston last week, I had the pleasure of seeking out plants and animals and rocks in one of my favorite environments: museums. Whenever I visit one, I like to see how artists incorporate something that means so much to me—the natural world—into their art, whether as the subject or as the medium.

In Boston, we spent about four hours in the Museum of Fine Arts. My first impulse was to notice the building stone, a muted gray granite quarried from Deer Isle in Maine. It’s a 300 million year old rock, widely used on the east coast. This was the mere tip of the geological wonders within the granite edifice. Walking the halls, I passed by a greywacke sarcophagus lid, a basalt lamp, sandstone walls from an Egyptian burial chamber, many limestone heads, countless marble heads, and a pair of travertine legs. And, then there were the totally cool, and clear, mica windows on model ships.

The first painting that drew my attention was of a Dutch landscape (~1655) by Aert Van der Neer. Gray and stormy, it depicts people in a snowstorm (with individual flakes, apparently a rarity in paintings) on a river surrounded by buildings. Snow covers the roofs, trees are barren and windblown, the river is frozen solid, and most of the well-clad people seem hunched with cold. It was quite the contrast to the weather in Boston; part of the reason we spent so much time in the MFA was the wicked-ugly heat and humidity outside.

Not simply a chilly scene, the painting depicts the Little Ice Age, a period (~1300 to 1850) of global cooling that hit northern Europe particularly hard. (In the Cascades, the LIA led to glaciers extending more than a mile further down valley than they do at present.) Over the past few decades researchers have used paintings such as Van der Neer’s to provide a more nuanced understanding of the LIA and how it impacted the landscape, people, and art. For example, a meteorologist who examined more than 12,000 landscape paintings completed between 1400 and 1967 found that artists working between 1550 and 1849 preferentially produced the most dark and stormy skies. Researchers also got a better picture as to how people adapted, such as frost fairs and skating on frozen rivers.

Soon after my trip to the Little Ice Age, Marjorie and I took a docent-lead tour. One of the images our guide took us to was a stained glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany. He, the guide not Louis, told us that some art historians consider stained glass to be the first truly American art form, led in part by Tiffany. I was certainly overjoyed to learn this but what excited me was how Tiffany incorporated Carolina parakeets (Conuropsis carolinensis) into his art.

The only parakeet native to what is now the United States, they were on the verge of extinction when Tiffany illustrated them, due to deforestation, habitat destruction, and the obscene desire for feathered garments. According to a booklet by museum curator Nonie Gadsden, Tiffany made the image based on Audubon’s Birds of America, which Tiffany owned. He could have highlighted the parakeet to draw attention to an American species that might soon not exist, hypothesized Gadsden. Sadly, this is not the lone example of art that depicts species that our species has driven to extinction.

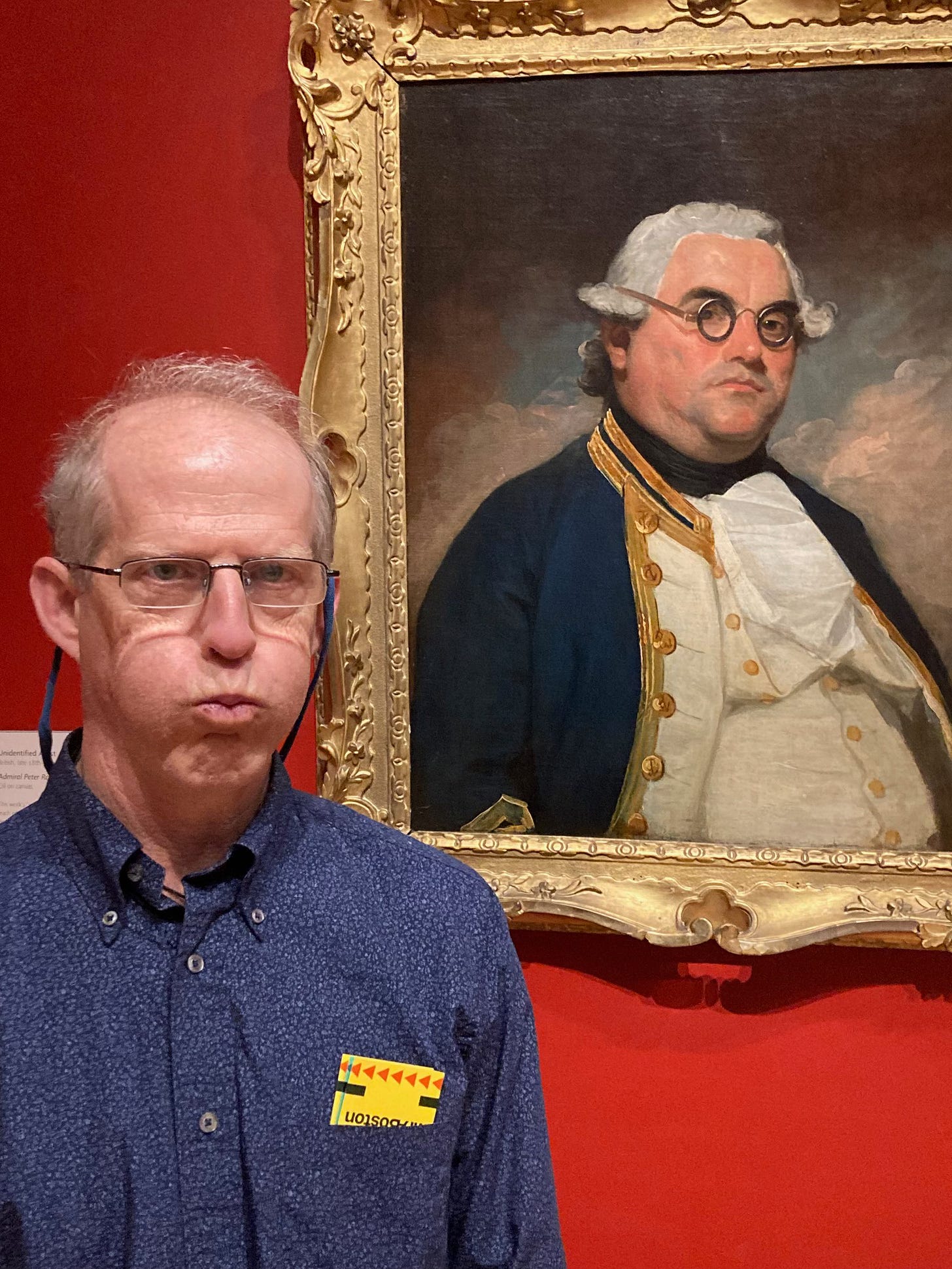

And, finally, not far away, I found an old friend. There in living color was Peter Rainier, painted a few years before George Vancouver bestowed his friend’s name on Tahoma (or Takoma). It was quite a shock, and clearly inspiring, to run into the painting of Peter, especially in a room with no other connection to the PNW.

Over the years, I have learned that museums such as the MFA are excellent locations to nourish my naturalist needs. I always find some interesting tidbit of nature to spark my curiosity, no matter the style, the artist, or the medium. To paraphrase what I’ve long said about architecture, there’s a lot of bad art out there (or at least art that I don’t like or understand) but if I take the time to focus on what interests me (and make funny faces) I come away happy and fulfilled, and generally in appreciation of what the artist was trying to do.

Word of the Week - Greywacke - An Anglicization of an old German mining term—grauwacke—meaning “grey earthy rock.” British geologists used the term in the middle 1800s as a “a sort of limbo for the reception of every thing that was ancient or obscure in the geology of England,” wrote amateur geologist William Fitton in 1841. Greywacke now generally refers to a dark, coarse-grained sandstone with more than a 15% clay matrix.

Me on TV. I was interviewed for King 5 Evening News and it aired the other day. Here’s my favorite quote: “So if you see a guy patting a building in downtown Seattle…Now you know, it’s just David B. Williams appreciating his wild urban home.”

July 22 - Birds Connect Seattle - 6:00 P.M. - Who’s Watching You? - I’ll be leading my downtown walk exploring carved and terra cotta figures.

August 12 - Birds Connect Seattle - 6:00 P.M. - Stories in Stone - I’ll be leading my downtown walk exploring building stone ranging in age from 120,000 to 3.5 billion years old.

Share this post