Yesterday the temperature peaked at 82 degrees in Seattle. That ain’t right. Our normal high for May 28 is 68 degrees. So, like any good Seattleite in such a dire situation, I panicked and sought out whatever cooling I could find: cold drinks, our basement, and stories of cold, such as people freezing to death and resorting to cannibalism on mid-19th century Arctic expeditions. Being the kind and kind of writer I am, I’ll spare you the details of the Arctic diet and instead relate another story of cold, which I hope helps my fellow Seattleites, and others who dwell in heat, to cool down.

Few animals better exemplify the cold than mountain goats. Indeed, one might even call them relicts of the last Ice Age, that is animals best attuned to a world of ice and snow. In other words, they are chionophiles, or snow lovers. As such, they inhabit the high country of the Cascades, with superb adaptations to the challenging terrain and inclement weather.

In order to navigate their rocky, icy world, mountain goats rely on their unusual hooves, each of which has two, pointed toes made of hard keratin wrapped at the base in a pliant, coarse pad that extends beyond the keratin. This combination of pointed, hard, and textured acts like Velcro, providing traction on a variety of surfaces. Mountain goats can also spread their toes and grip uneven terrain, sort of like a wrench. It’s a bit of a stretch but mountain goats could be called a well-muscled mountain octopus equipped with eight clinging devices, a superb sense of balance, and low center of gravity.

In order to survive the cold of the high country, mountain goats rely on their dense fur. One study found that as winter approaches, they increase their insulation to more than eight times greater than in summer. They accomplish this cold protection by growing guard hairs up to eight inches long and a dense undercoat of twisted, interwoven, one- to two-inch-long hairs, sometimes called wool. Then, as the weather warms, they shed their fur, often in sizable tufts. Despite this, mountain goats still often have to bed down, or seek out shade or snow patches, to avoid overheating, in the summer.

Several years ago, I watched a band of mountain goats on Mount St. Helens. Many of the adults were shedding, the shimmering white swaths reminding me of calving glaciers. This yearly shedding of wool has long been important to Native people of the region, who collected the fur and wove it into blankets, robes, and other clothing. Valued for their beauty, durability, lightness, and warmth, such garments were often limited to wealthier people or those of higher standing. When I found some of the wool at Mount St. Helens, it was dense and soft and dotted with needles and small sticks. It didn’t feel oily or have any aroma.

The insulation properties of mountain goats has also attracted those less interested in aesthetics and more attuned to keeping people warm. Such researchers focus on the ability of a coat of hair to trap air and resist heat transfer between one’s body and one’s environment. For instance, a 1968 study that included some rather fancy mathematical equations described three classes of hair coats. 1. Dense and matted coats of crimpled hairs, as exemplified by domestic sheep. 2. Dense coats, on the order of 4,000 hairs per square centimeter, as in small mammals and Arctic species. 3. Coats of long strong hairs, which have densities of just a few hundred hairs per square centimeter. The last is the category of mountain goats.

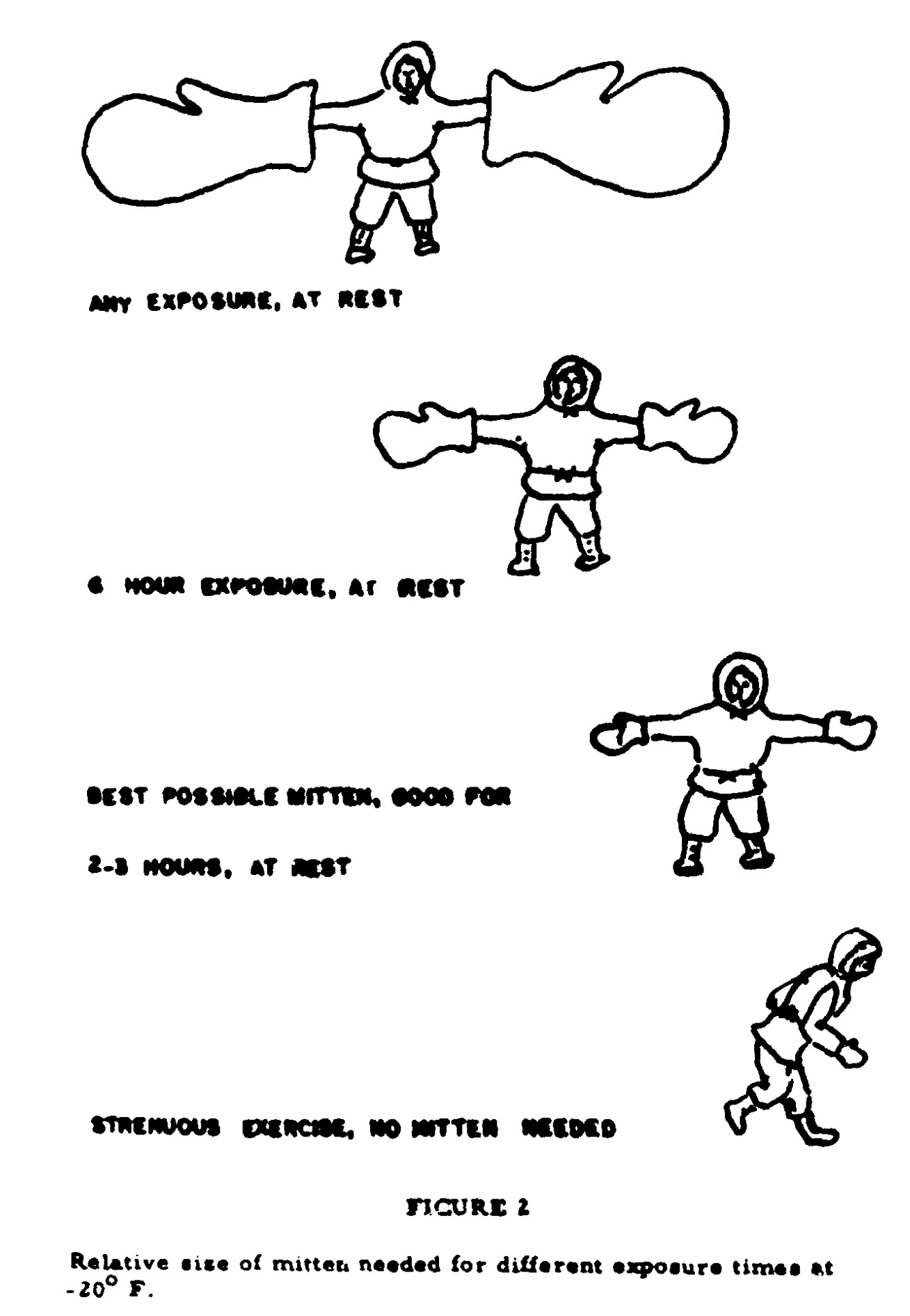

In another study, published in 1964, Arthur Goldman of the US. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine sought out solutions for keeping an inactive person warm for eight hours at minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit in a three MPH wind. Unfortunately, the complete Army Quartermaster, cold-dry standard clothing ensemble, which totaled 35 pounds, was not up to the task. The problem was matching the needs of the torso and the extremities; the only way around this was supplemental batteries that provided auxiliary heat, or some darned huge mittens.

In the study, Goldman referred to the “unit of thermal insulation,” which is known as a clo. One clo of insulation is defined as “‘everyday clothing,’ roughly that of a man’s business suit plus vest, pants, shirt, socks, and shoes.” He noted that the Army’s top line, but inadequate, insulation suit had a rating of 4.3 clo. Not until several decades later, was the clo determined for mountain goats. Their dense coat provides about 5 clo. Clearly, these beasts of the mountains are well adapted for the cold and would have been even more grumpy than any Seattleite was yesterday.

With the temperature heading back to normal in my fair city, I rejoice, and celebrate. I am glad that I am neither clad in a fur suit I could wear in the Arctic nor wearing gloves as big as my body. Of course, if I did don the latter, I like to think that it could be the start of new fashion trend. Stay cool everyone.

Thursday, June 12, Third Place Books, Lake Forest Park - I am truly honored and humbled to be interviewing Robert Macfarlane about his newest book Is a River Alive? It’s quite stunning, revelatory, and provocative. I am very much looking forward to the opportunity to chat with him. Reservation required.

And, again, here’s a link to my Wednesday show on Space 101.5 FM. This one is about the Seattle Fault Zone and the researchers who used trees to date when the fault hit.

Info on three types of animal coats: K. Cena and J. A. Clark, “Thermal Insulation of Animal Coats and Human Clothing,” Physics in Medicine and Biology, v. 23, n. 4, 565-591, 1978.

Illustration of gloved guy: Ralph F. Goldman, “The Arctic Soldier: Possible Research for Solutions for His Protection.” US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, MA 1964.

Share this post