What is it with birders and birding in fictional TV and movies? They seem to go out of their way to make poor observations and incorrect identifications. I know you might be shocked but there’s an infamous ornithological blunder in the 2000 remake of “Charlie’s Angels.” The angel played by Cameron Diaz ferrets out the evil villain’s lair by a bird she hears in a recording. Ms. Diaz claims the bird, supposedly a Pygmy Nuthatch, “only lives in one place—Carmel, California.” Tell that that to the nuthatches who inhabit the ponderosa pine forests of eastern Washington. The movie eventually shows the “nuthatch,” which turns out to be a Venezuelan Troupial, a bird that lives in…Venezuela. Plus, the bird song comes from a Thick-Billed Fox Sparrow. Despite the preposterous inaccuracy, Ms. Diaz and her pals find the villain and save the day. The movie is equally as bad as its birding.

Much more common in the error department are the overused bird tropes: the calls of Red-Tailed Hawks and Common Loons. Both are “indicators” of wild places, no matter where, the time of day, the season, and often the bird on the screen. For example, with their screeching cry, red-tails are regular voice-ins for the whiney, less-than-wild, less-than-noble Bald Eagles, such as in the Lord of the Rings films. The haunting, wailing sound of the loons pops up around the cinematic world from 1917 to Harry Potter to Godzilla.

My most recent encounter with a fictional birder is Cordelia Cupp. She’s the star of “The Residence” (Netflix). A consulting detective, like Sherlock Holmes, she’s called in to solve a murder in the White House. She’s a wonderful character, full of verve, quick wit, and practical smarts. She makes the show a joy to watch.

Like many mystery personalities—Hercule Poirot and his fastidious mustache, Endeavour Morse and crossword puzzles, and Sherlock Holmes and his uncountable obsessions—Cordelia has an idiosyncrasy that helps define her character. Throughout the series, she regularly disappears to go birding and stops in the middle of a scene to notice a bird, after which she offers an explanation of the bird and how they help her be a better observer.

In one scene, her sort-of-partner, FBI agent Edwin Park (who is also a wonderful role) says: “She told me earlier in the day that this sometimes happened in the field when she was out looking for birds. ‘She said that the only thing you can do is wait and that it would come.’” In regard to seeing a falcon, she says: “It’s the way that they can identify even the most imperceptible of weakness in their prey.”

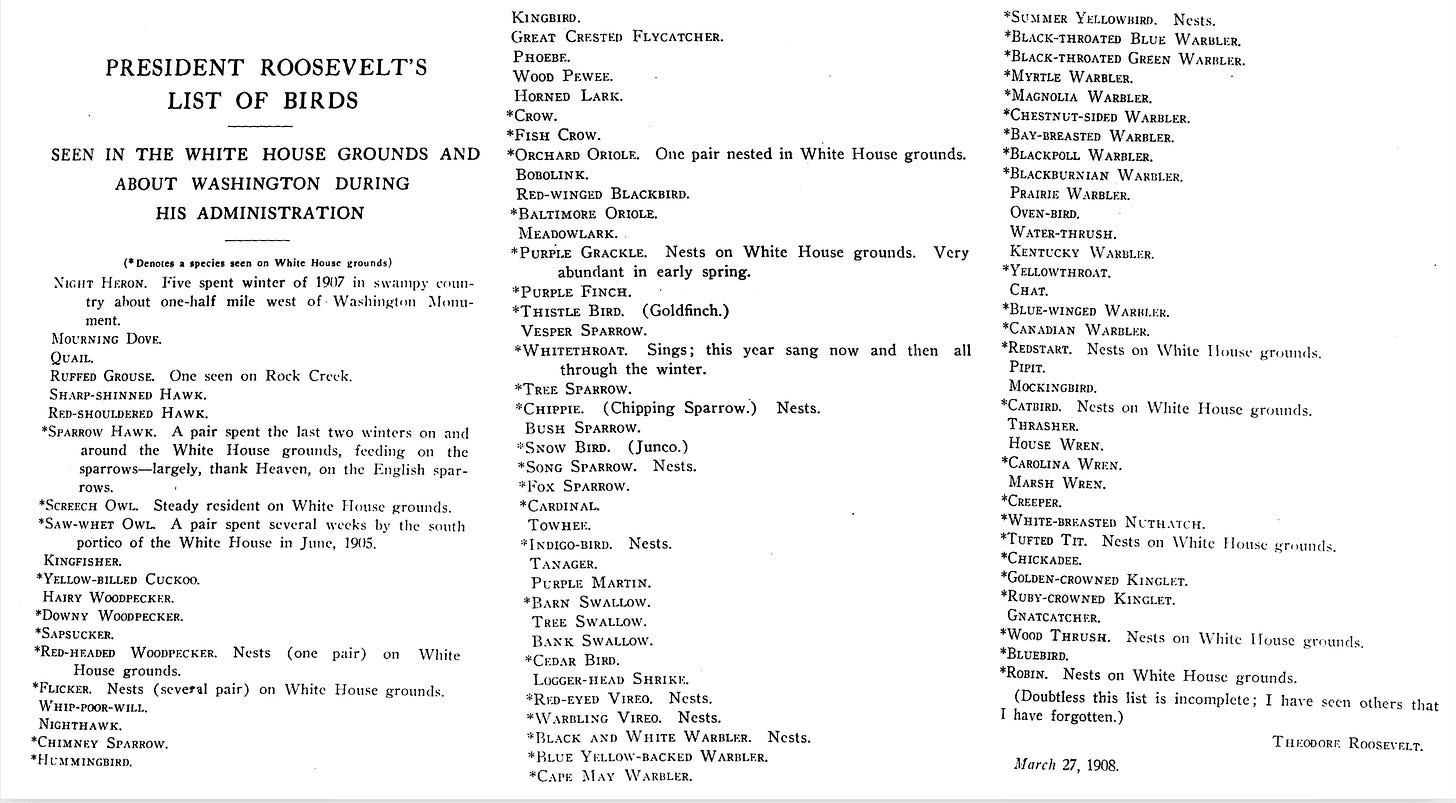

Woven through the show is Cordelia’s goal of ticking off all the birds (hence the term tickers for birders) on a list made by Theodore Roosevelt when he lived in the White House. He had been prompted to compile it by birder Lucy W. Maynard. “I explained that I wanted it for a new edition of the local bird book Birds of Washington and Vicinity [which Maynard wrote]. ‘Why yes,’ he answered cordially. ‘But I’ll do better for you than that. I’ll make you a list of all the birds I can remember having seen since I have been here.’” The list appeared in the 1909 edition of Ms. Maynard’s book.

Roosevelt’s list is impressive. Clearly he knew his birds and he also paid attention and noticed what was going on around the grounds of the White House. (I cannot imagine the present resident noticing anything wild or natural on the grounds.) Note the number of species that he saw nesting on the White House grounds, as well as the three birds of prey—Screech Owl, Saw-whet Owl, and Sparrow Hawk (now called American Kestrel) that resided or spent several weeks there. I am further charmed by Teddy’s observation about the Sparrow Hawk. “A pair spent the last two winters…feeding on the Sparrows—largely, thank Heaven, on the English sparrows.” (English Sparrows are a non-native bird, long disliked by many but that’s a story for another time.)

In order to make the show and Cordelia bird-friendly and not bird-inane (as in Chuck’s Angels), the producers hired legendary birder Kenn Kaufman as a consultant. Kaufman later wrote about his experience and referenced a part that I found slightly annoying: a falcon flying at night around the White House. Cordelia makes the point that she desired to see a falcon (based on the list) and even shows us (the viewers) the name on the list. Unfortunately, no falcon is listed though the American Kestrel is a falcon and the one shown on screen is “generic large falcon,” according to Kaufman. It’s “a metaphor, a symbol,” he added. I get it but couldn’t they have “made up” an owl instead; they are night flying birds. Oh well.

More importantly, and to the producer’s and writer’s credits, having Cordelia be a birder is a wonderful way to introduce people to birding. They show that birds are all around us, even in the most urban of settings; that birding gets people to pay attention and to think about and notice the natural world around them; and that we can learn about ourselves and our place in the world by being more observant and more centered. Plus, if the situation arises, and I hope it doesn’t for any of you, birding may help solve a murder mystery.

Word of the Week - Kestrel - In 1573, in the Thesaurus linguæ Romanæ and Britannica, Thomas Cooper wrote of what he called the tinnunculus: “a kinde of haukes; a kistrell or kastrell; a steyngall. They use to set them in pigeon houses, to make doves love the place, because they fear away other haukes with their ringing voice.” Thus, according to Ernest Choate’s The Dictionary of American Bird Names, kestrel, which was first used to describe the European Kestrel, “may come from its call.”

— Wow, a splendid review of Wild in Seattle. Here’s a little excerpt and full review. “Exceptionally well written, illustrated, organized and presented, Wild in Seattle: Stories at the Crossroads of People and Nature by author David Williams and artist/illustrator Elizabeth Person features more than 40 essays that dive into the geology, animals, plants, and architecture that shape Seattle. Of special note are the many fun and fascinating sidebars exploring regional vocabulary, scientific terms, and Indigenous language phrases.”

Share this post