Seeps. Springs. Rills. Brooks. Creeks. Streams. Rivers. A web of water tendrils entwines the landscape and provides habitat, transfers nutrients and sediments, creates travel corridors, and bestows beauty.

Veins. Arteries. Neural Networks. Life blood. Life. What are rivers but breathing, living centers essential to the health of the environment for the more-than-human and human world we all inhabit.

I was prompted to write this newsletter by reading Robert Macfarlane’s new book Is a River Alive? Not surprisingly, considering his previous books, such as Landmarks and Underland, it’s provocative, filled with elegant and moving prose, and offers a profound way to consider one’s relationship to place and the world. I hope to write about Is A River Alive? later but wanted to home in on a specific observation he makes. “Everyone lives in a watershed.” It’s an obvious and true statement but I hadn’t considered it before.

For Macfarlane, he writes in regard to his watershed: “My waters are the River Dee, who rises in the Cairngorm plateau, bubbling out of the plateau granite…and [a] nameless stream” near his home in Cambridge, England.

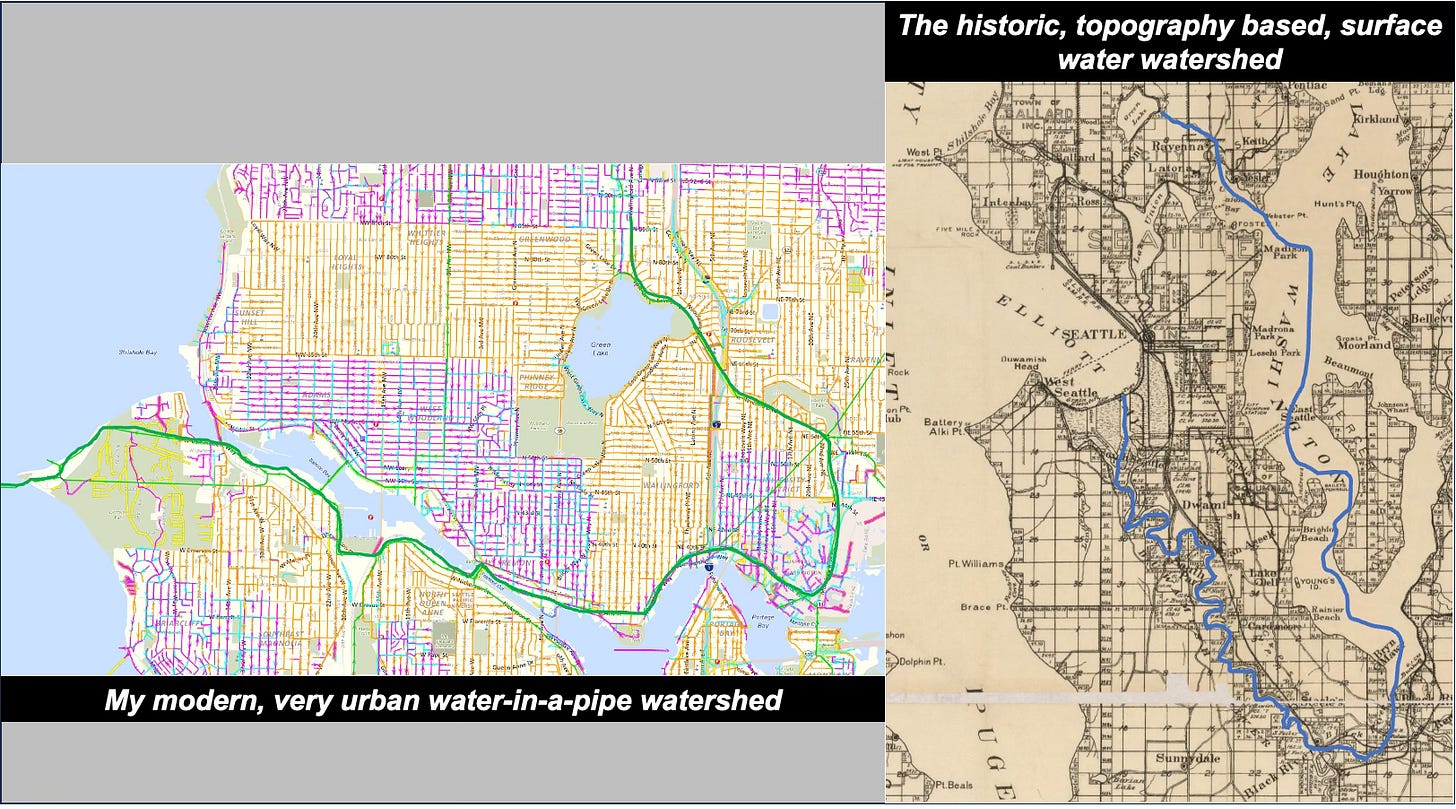

For me, I’ll start with an historic perspective. My waters are a small creek who flows south from liq’ted (Lushootseed for place for red paint), or Licton Springs, small springs rich in iron oxides. liq’ted enters dxʷƛ’əš (unknown translation), or Green Lake, with an outflow to the east down Ravenna Creek (no known Native name), who flows into xačuʔ, or Lake Washington. The big lake outflowed south out through Mox la Push (a Chinook jargon term meaning two heads, in reference to when the river flowed in two directions with high water in the Cedar River), or the Black River. Next came the dxʷdəwʔabš (Lushootseed for people of the inside), or the Duwamish River, with a final connection into a bay of Whulge (Lushootseed for the salt), or Puget Sound. Total length ~ 34 miles

(After 1916, and the completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal and Locks, this route has been abbreviated to the unnamed creek to Green Lake down Ravenna Creek to Lake Washington and out the Ship Canal to Puget Sound – Total distance ~ 11 miles)

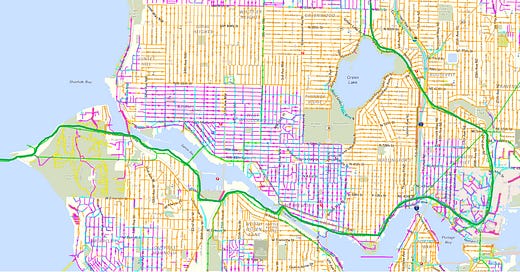

My modern watershed is more prosaic. Water and sewage from our house and nearby impervious surfaces (street, driveway, sidewalk, etc.) enter a pipe that extends south to Green Lake and the North Trunk Sewer line, which runs under the old route of Ravenna Creek, down toward Lake Washington, along the north side of the Ship Canal, cuts across the Fremont Cut, and ends at the West Point Treatment Plant at Discovery Park. Total distance also ~ 11 miles

My modern watershed reflects what many people in cities experience. Most, if not all, of the many small waterways who formerly threaded the landscape have been buried, captured, or graded out of sight. They have, as I have written previously, become Ghost Creeks, no longer seen but sometimes rising up and reminding residents of the past and how the landscape used to function. Another important aspect of rivers to urban residents is how they often dictated where cities and towns located. People needed the waterways for navigation and the water for drinking; by losing these connections we lose deep links to the stories that define a place.

Freshwater generally has a single goal, to return to the sea, or, in other words, to follow the gravitational pull to the lowest point of topography. (I am, of course, excluding all of the water that seeps into the ground.) A watershed is simply the area of land that collects and feeds a single waterway, from the smallest creek to the biggest river. (Other terms are drainage basin or catchment basin.) Living here on the coast, my watershed is quite small and my water travels not far, from my home to Puget Sound. But consider my good friend Jeff, who lives in Louisville, Colorado: his water ultimately travels nearly 2,400 miles to reach the sea at the Gulf of Mexico.

By inextricably linking water to the land that surrounds and feeds the riparian systems, what a watershed makes clear is that what we do on the land is as important as what we do in the water. Consider the watershed of Puget Sound. Whether it’s farmers using pesticides, residents dumping pharmaceuticals down their toilets, industries washing toxic substances into creeks, or hatcheries treating fish with antibiotics—each impacts the health of this watershed home of several million people. Restoring, maintaining, and sustaining functioning watersheds requires not only clean, healthy water but also clean, healthy land that drains into the water.

Ultimately, a watershed is a community, a community of people, plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria, each interacting with the landscape and the waterways who flow across the land. As with any good and strong community, the health of the whole is directly tied to the health of individuals. Even in a modern watershed, such as most of us inhabit in our urban lives, we are part of this community, responsible to others with whom we share this space, this place, these waters.

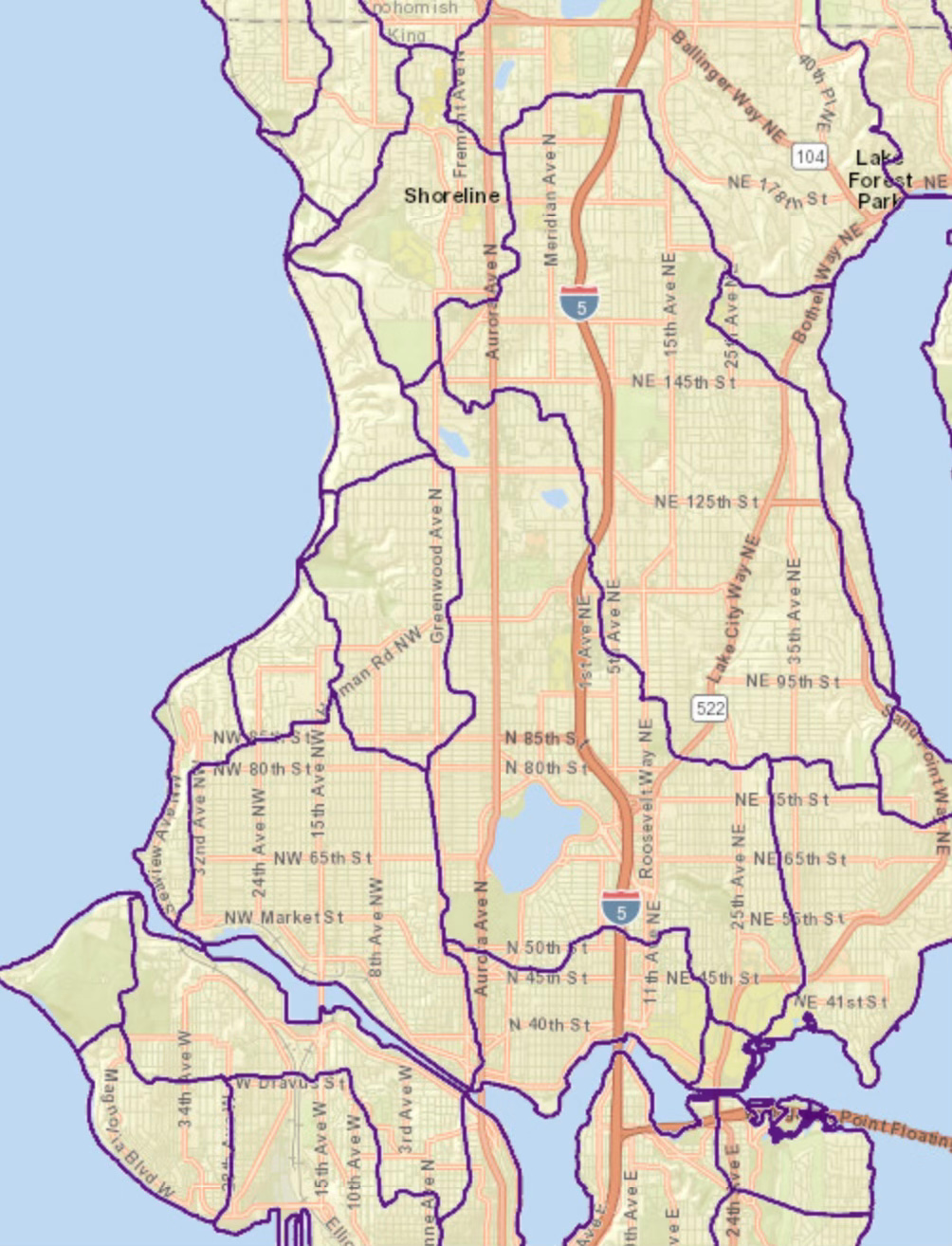

In case you are interested in determining your own watershed (at least in the Puget Sound region), here’s the best source I know of: the Washington Department of Ecology’s Puget Sound Watershed Characterization Project. What I found that works best is to do the following: Click on “Reference Layers” on the left-hand side, and then check the box for “Watershed Management Units.” The new map will show the boundaries of localized watersheds.

Another fun and helpful watershed website to use is this one produced by journalist Sam Learner. With it you can pick any spot and see the route water travels from land to the sea. The site will even “fly” you down the path. It’s quite a fun way to waste time and to see who you share your waterway with.

Thanks to Patrick Trotter and Jason King for sharing some of their amazing work detailing the watersheds and creeks of Seattle. It is opening a new way of seeing Seattle and the interconnectedness of the landscape, people, flora, and fauna. Here’s part of one of the maps they have compiled, which shows the watersheds near my home in north central Seattle. Thornton Creek (on the upper right side of the map) has the city’s largest watershed.

Share this post