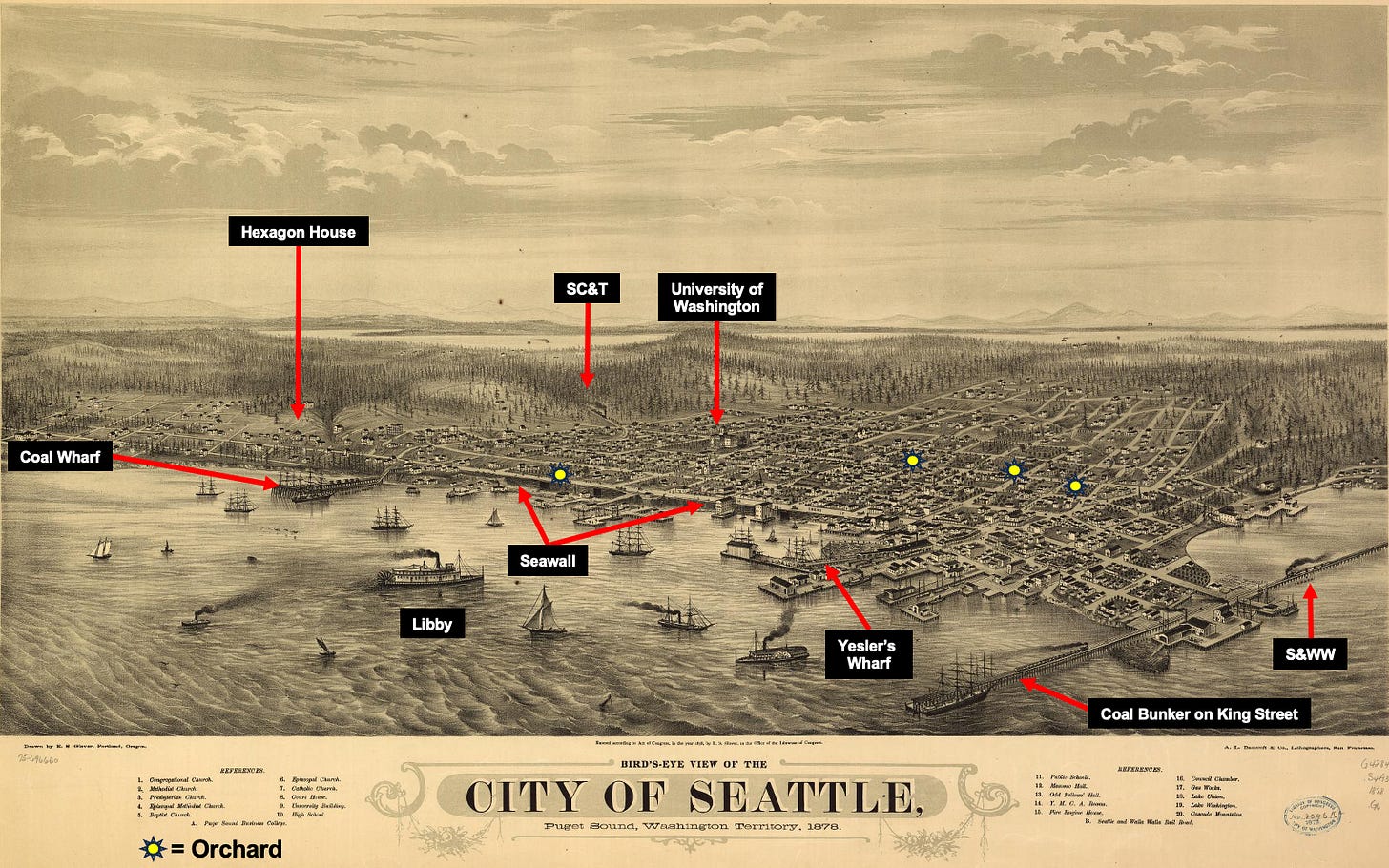

In early January, I wrote about one my favorite images of Seattle, August Koch’s 1891 Bird’s Eye View. I’d now like to return to another similar map: Eli Sheldon Glover’s 1878 Bird’s-Eye View of the City of Seattle. An itinerant artist, Glover produced similar panoramas of Tacoma, Portland, Walla Walla, Olympia, and Port Townsend. Glover’s is the first of this style of illustration done for my hometown. Just 3,200 people lived in Seattle when Glover executed his drawing.

The most curious feature of the illustration is Glover’s regrading of the city. He has flattened Seattle’s steep downtown hills, giving a viewer the impression that the city is pancake flat instead of challengingly hilly. In fact, nearly every road in downtown Seattle was steeper in 1878 than at present. As an example of Glover’s ironing of the landscape, note how Denny Hill barely rises at the north end of the image. Compare his drawing of what was known as the hexagon house with an actual photo. (Glover tended to be accurate with his buildings.) Located just above the coal wharf at the north end of the waterfront, the infamous, three-story structure was built in 1875 by foundry owner John Nation. In the photo below you can see it was actually perched on a bluff overlooking the corner of Front (named because it was the waterfront) and Virginia streets and not on the relatively flat spot Glover created. The house didn't survive the 2nd Denny Regrade of 1903.

Glover did get one topographic feature right. He showed how bluffs rose abruptly out of Elliott Bay. Prior to the creation of Alaskan Way (originally Railroad Avenue) on garbage and fill and the wholesale change of the waterfront, steep bluffs rimmed the bay. They still exist but are built over by roads and buildings. Only a small remnant of this original (sort of) bluff remains visible in downtown. Hidden behind a building on Alaskan Way, it extends for about a block north of Lenora Street. Another good place to see what the downtown bluffs used to look like is Discovery Park, where a steep face of clay, sand, and silt rises from the beach.

Between Marion and Union streets, you can also see Seattle’s first seawall, built of log cribbing in 1876. This project included Seattle’s first regrade and first large-scale attempt to rebalance the terrain in favor of people and commerce.

Where Glover excels is in his depiction of commerce. The city’s reliance on shipping can be seen in the dozen-plus wharves and the abundant water traffic. Most look to be trading vessels—both sailing and steamer—with a few pleasure craft and canoes. The only named ship is the sidewheeler J. B. Libby. Launched at Utsalady on Camano Island in 1862, the Libby was one of the first built and best-known steamers in Puget Sound. That is until the 80-foot paddlewheeler caught fire and sank in 1889, the fate of many another Mosquito Fleet vessel.

Glover also illustrates an early and often overlooked aspect of the growing city: coal. Just left of center in the full view, a train emerges from between two, wooded, and geographically odd hills. By odd, I mean that those hills do not and did not exist. The train, Seattle’s first (March 1872), was operated by the Seattle Coal and Transportation Railway. It was transporting coal mined on the east side of Lake Washington, barged across the lake, carried overland to Lake Union, and barged across that lake to a train depot at the lake’s south end. The coal’s destination was the big wharf, or bunker, at the end of Pine Street.

At the south end of downtown is another coal wharf. This was the end point of Seattle’s second train, the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad (March 1877). Planned to reach what was then the largest town in the territory, it only made it to about Renton. This may seem to be a typical, over-hyped Seattle transportation project but in reaching the east side of Lake Washington, the train could tap into the burgeoning coal industry. With the S&WW running, Seattle’s coal exports boomed from about 7,000 tons/year to more than 100,000 tons/year. With coal now able to reach the coal bunker on King Street via a single railroad, the SC&T Railway closed.

In addition to coal the other big business was lumber. Several booms of logs are floating along wharves, including the massive Yesler pier, at the base of Mill Street (now Yesler Way.) Also, note the city’s biggest building, the University of Washington. Designed by John Pike (of Pike Street fame), it was built in 1861 and survived until 1910. The university still owns its original property, home to the Rainier Tower (aka The Pencil), Olympic Hotel, and Rainier Square (aka the Kinky Boots tower).

The final part of Glover’s image I’d like to highlight are the orchards. (Shown on map above.) Most were probably private ones, owned and maintained by home owners, such as Catharine and David Blaine and Mary and Arthur Denny. In a time when supermarkets hadn’t yet been invented, many people were far more self sufficient than today. Those industrious orchardists could have bought their trees from C. L. Lawton’s Seattle Nursery. His stock included 50 varieties of apple, 40 varieties of pear, and 11 varieties of peach. And, we think we have a wide selection of fruit in stores.

Early Bird’s Eye View panoramas of cities were primarily about celebrating the achievements of settlers. These maps were all about the dynamic spirit of young and growing towns and the image they wanted to project. No indication is made of the Indigenous people who had been displaced. Nor are any of the buildings or boats run down or dilapidated. All is good. The future is bright. Long live Seattle.

April 8, 2025 – Waterfront Walk – 10:00 A.M. – I’ll be leading a walk along the historical Seattle shoreline for Friends of Waterfront Park. Here’s a link to register.

Share this post