As a map and geography dork, one of my little pleasures is being a gnomon. This is particularly true when my shadow is directly in front of me as I walk north on a city street. When that happens, I know it is celestial noon because most streets in most cities are laid out due north/south, which means you also have a gnomonic ability. Therefore, I was confused when walking up Fifth Avenue in downtown Seattle. (I was also a bit taken aback simply by the sun being out in late November.) The reason for my confusion was that my shadow pointed directly up the street, like a sundial at noon, which meant it should be noon. And, it wasn’t!

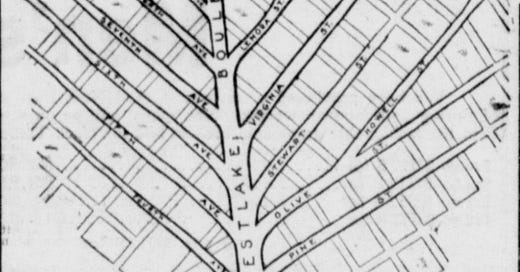

I quickly realized my mistake, which I knew resulted from a geographical quirk created by early Seattle settlers Arthur Denny and Doc Maynard. In 1853, they were tasked with platting Seattle streets. Legend holds that Denny believed that Maynard was “stimulated by liquor” and that he had the gall to align his streets with the cardinal directions. In contrast, Denny (a notorious teetotaler) aligned his streets with the shoreline.

Both were right in their actions. Most urban and rural settings operate on a cardinal direction street orientation, basically a Cartesian grid, aligned north/south and east/west. Thus Maynard was simply following historical protocol, when he created his street grid south of what is now Yesler Way (nee Mill Street). Denny’s idea was also logical. An alignment tied to the waterfront would make it easier to navigate to, from, and along the shoreline, certainly a key issue in a city whose economic life centered on maritime trade.

The two couldn’t compromise because Denny believed that “Maynard had taken enough to make him feel that he was not only monarch of all he surveyed but what…I surveyed as well,” wrote historian Murray Morgan, in his book Skid Road. Ironically, Denny had been a surveyor so should have known and accepted Maynard’s logic of alignment with the cardinal directions. The conflict between the two fellows is what led to my confusion because my shadow was oriented with Denny’s waterfront roads, thus altering the normal time-space continuum of noon shadows and north/south roads.

I can easily imagine that many of you are now wondering: Does Seattle have other big downtown road quirks that mess with David? Well, readers, look carefully and you can see that Second Avenue Extension South (created in 1928/29) is the only street west of I-5 that cuts straight across the Maynard-Denny Line of Contention. All others follow the kink created by the original plats. Builders of the new road hoped that a direct connection from the more prosperous northern part of downtown would drive “better” money and business to the area known variously as Blackchapel, Whitechapel, the Lava Beds, Tenderloin, and perhaps most famously, Skid Road. The straight-line extension would also help alleviate congestion, which was becoming more problematic with the growing popularity of automobiles.

To the north lies the other notable road idiosyncrasy. Like the 2nd Avenue Extension, Westlake Avenue cuts through the established road grid, this time at yet another angle different not aligned north/south. Built partially with fill from Denny Hill between 1905 and 1907, the road ran in what some called the “great Westlake Valley,” an area where surveyors in 1856 reported six-foot-wide western red cedars. Westlake Boulevard, as it was originally known, would be the new arterial highway bringing prosperity for property owners and businesses along it and to the north, unless of course the city condemned and appropriated your property. Oh well, you can’t please everyone.

The story of Seattle’s downtown street grid is the typical one of a thriving and ambitious city, particularly one obsessed with becoming a WORLD CLASS CITY. Initially, the layout follows the topography, often tracking old footpaths, which in turn might follow routes utilized by the Native inhabitants, or perhaps even animals. As the city grows, roads get more formalized through official platting, and less tied to topography via regrading. Eventually, enough changes occur, such as the arrival of new modes of transportation or development of more outlying areas, to force planners to slice across the grid. I get their point that following that ancient observation—the shortest distance between two points is a straight line—is a good idea but it really messes with my ability to tell time.

Speaking of streets, today’s as good of time as any to announce the imminent publication of the Second Edition of Seattle Walks. I have updated the walks, fixing mistakes and addressing changes in the urban infrastructure. I also added three new walks—in Georgetown, the Central District, and Cascade/South Lake Union—and dropped two walks—Magnuson Park and Where You At? Seattle Walks won’t be out until February 2025 but you can pre-order it through the UW Press and get a 40% discount until January 3.

Share this post