My story last week about the herring caught by the Osprey reminded me of another flying fish tale. This one is even nuttier, with longer lasting consequences.

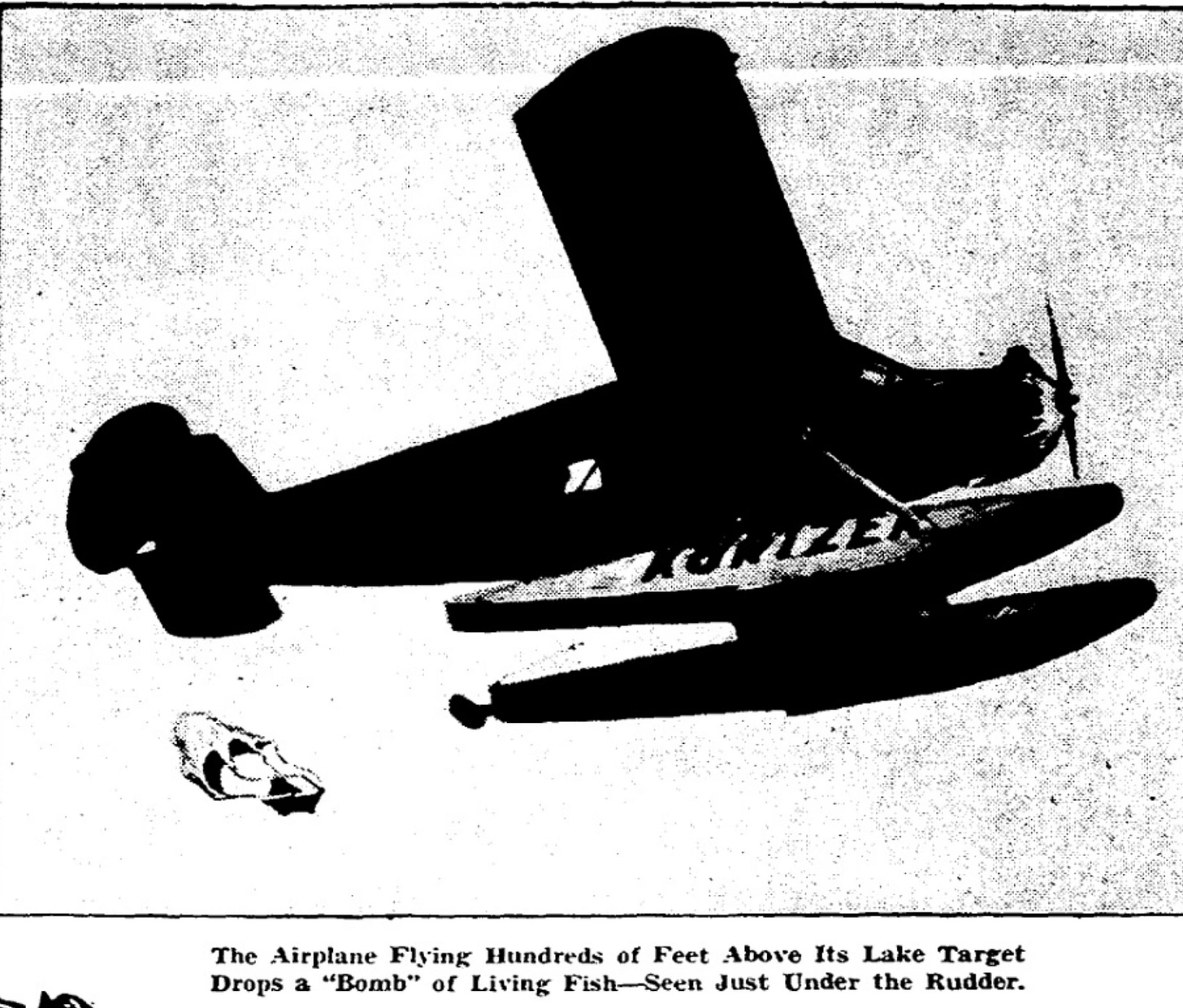

If you were standing on the shore of Lake Washington on September 15, 1938, you could have seen 2,000 flying trout. They came from a low flying plane, which dropped the fish fingerlings in a rectangular metal can attached to an old gunny sack fashioned into a parachute. The fish bombers experimented during several flights, varying the size of the can and the parachute. They then recovered the cans and discovered that the several-inch long fish were “not dead, injured nor apparently even excited over this experience,” according to a Seattle Times reporter in an article two months later. The aerial ichthyologists also figured out that they had to starve the fish for two days prior to the flight or the airplane trip made them sick. (Nothing’s worse than an airsick fish!)

The final challenge was getting the fish out of the “floating prison” of the can after it landed on the water and had its opening on its top. The solution was to attach a block of wood to the bottom of the can so it would flip over after it landed and dump the fish in the water.

A man named Alvin Carlson had suggested this method of lake stocking to the Washington Game Department (now Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife). He was a member of the Trail Blazers a group formed in 1934 “to help make this wonderful State of Washington a fisherman’s…paradise.” They still exist and are still helping to stock lakes. Carlson was searching for more efficient ways to spread fish to high country, hard-to-reach lakes. He had initially suggested pouring out the fish from a plane flying just over the water but this was deemed too dangerous. Thus the idea of flying high and parachuting the fingerlings.

On the day following the Lake Washington flights, Game Department personnel proceeded to the high country. They flew in a single-engine float plane up to the mile-long Otter Lake at 4,400 feet, about 12 miles northeast of Snoqualmie Pass. The men carried ten cans with a total of 12,000, inch-and-a-half fry on the plane and dropped them from one thousand feet above the lake. About a third of the cans missed the lake or overturned in flight. Two years later, a group of Trail Blazers hiked the nine miles up to Otter Lake and found that those Adam and Eve rainbow trout fry had grown into thousands of ten- to thirteen-inch fish. They were “fighting fools…well distributed all over the lake,” said Carlson, to a Seattle Times reporter in July 1940.

The Washington Game people weren’t the only state employees to rain fish into lakes. In California they took a different approach when, in 1949, former barnstormer pilot Al Reese froze fish into blocks and parachuted them into lakes in ice cream buckets. It was not a success. Next, he let a five-gallon can free fall from 350 feet above the lake but it hit rock instead of water. Surprisingly, a few fish survived in the remaining water, which prompted Reese to eventually let the fish free fall by themselves into a lake. Within a few years, several states had turned to stocking by air but it’s unclear how long Washington state employees continued the can-based method of stocking fish into high lakes. (One unanswerable question is how many metal cans are resting and rusting on the bottom of lakes across the Cascades.)

By at least the late 1950s, parachuting fish into lakes was no longer the preferred method for plane stocking the Cascades. Instead, WDFW had decided that it was better to go with Alvin Carlson’s original idea of simply flying low and letting fish free fall into the water. This practice continued until the late 1990s, despite what falling into lakes did to fish. One biologist who witnessed the showers of rainbow trout said, “many of the fish were ripped apart on impact…and many others were so stunned they immediately sank to the bottom, never to recover.”

WDFW continues to stock fish in the high lakes of the Cascades. Now, though, the most common way to do so is for people to carry fingerlings on their backs up to the lakes. It’s certainly a much less spectacular method but the fish are much happier.

(This newsletter is based on a much more detailed account of stocking alpine lakes that will be in my next book, which focuses on the human and natural history of the Cascades. It will be published in 2026.)

If you want to read about a few walks I suggested to writer Terry Woods for an article in the Seattle Times, here’s a link.

May 22 - Edmonds Waterfront Center - Edmonds - 6:30 - I’ll be in conversation about Wild in Seattle with the wonderful Tony Angell. Hope to see you there. Co-sponsored by Edmonds Bookshop.

And, don’t forget to listen to Space 101.1 FM, with me reading my essays from Wild in Seattle. If you listen, you’ll hear about 20 seconds of singing about whiskey, not by me, just the end of the previous show.

Share this post