George Davidson knew more about navigating the west coast of the United States than most people. He was, however, apparently a poor botanist, at least in regard to trees, though he was better at underwater botany, a far more important skill in Davidson’s line of work.

Born in England in 1825 but raised in Philadelphia, Davidson spent 45 years surveying west coast waterways for the US government. He began work as secretary to Alexander Dallas Bache, director of the US Coast Survey in 1846. Four years later he moved from the east coast to San Francisco and between 1853 and 1857 surveyed the greater Puget Sound region. One snarky biographer noted: “It appears that hope of monetary rewards and scientific fame motivated Davidson far more than the call of adventure, duty to his country or the spirit of scientific inquiry.” He may not have struck it rich but he certainly left his mark on generations of mariners.

During his years of surveying the Sound, he had occasion to name several features, such as Nodule Point (totally cool rocks!) and Whidbey Island’s Mutiny Bay and Double Bluff (no reason given for names); Duwamish Head; and the Quimper Peninsula (“No name has hitherto been applied to it, and we have ventured to designate it.”). Davidson also regularly noted down Native names, though he rarely used them.

In 1856, he named three peaks in the Olympics—Ellinor, Constance, and the Brothers—for his soon-to-be-wife, her sister, and her siblings (Arthur and Edward, though clearly their names were not worth mentioning), as well as Fauntleroy Cove, named for their father, Robert Henry Fauntleroy, also the name of his ship. Do you think he was buttering up the family to ask Ellinor to marry him?

In order to survey an area, Davidson would establish several base points he could use for measurements. One of those fostered his floral error. Just north of the little town of Seattle (“It consists of a few houses and stores, a church, and a small saw-mill. It has but little trade,” he wrote.), his map included the points Leaning Tree, Swallow, Alder, Trail (there was a Native trail from this location over to what is now Lake Washington), Buttonwood (which would be a lovely neighborhood name), and Magnolia. Davidson clearly chose those names based on natural features and it appears that he mistook our lovely native madrones on the bluff (their preferred habitat is well-drained soils and they were wide spread on Seattle’s bluffs) for the magnolia trees he could have seen in New England. As I wrote previously about Lt. McClellan, “Oh George!”

Fortuitously for mariners, Davidson spent more time focused on underwater plants, in particular kelp. In 1858, he produced the Directory for the Pacific Coast of the United States, a detailed guide for ship navigation. Later known officially as the Coast Pilot and unofficially as “Davidson’s Bible,” the book contained descriptions, horizon drawings, distance charts, latitude and longitude measurements, soundings, and bearings, basically any information a mariner would need to navigate safely in the waters between Washington and California.

Throughout the four editions he authored, Davidson provided copious details about kelp, where it grew and where it didn’t, how to tell current strength by the “drag of kelp,” and what to do in case of emergency and if one’s boat “should happen among it,”—seek out “lanes of clear water.” In his 1869 edition he wrote, “In coming to Steilacoom, or bound direct to Olympia, a patch of kelp, with foul bottom, and less than three fathoms of water upon it, must be avoided.”

Davidson helped chart Puget Sound, too, producing the Coast Survey’s Topographic Sheets. These T-sheets, as most mariners know them, were nearshore reconnaissance depicting unprecedented navigational details, including kelp. On the chart that shows Steilacoom, numerous snake-like squiggles, the symbol for kelp, envelop the shoreline at the mouth to Chambers Creek, the north and sound ends of Ketron Island, and down long sections of the east side of Cormorant Passage, leading to Olympia.

Because of the kelp, or the rocks it was anchored to, and other obstacles, Davidson wrote “it would be almost useless to attempt to describe the route between Olympia and Steilacoom because a pilot or a chart is absolutely necessary in making the passage.” Ultimately, Davidson concluded in a September 18, 1854, letter to Bache: “The deduction is short—always avoid the kelp.”

In an August 24, 1952, Seattle Times article Lucille MacDonald wrote about Davidson’s life: “It is said that for 60 years [he died in 1911] his name was more familiar to scientifically inclined persons on the Pacific Coast than that of any other resident.” He is certainly not as well known at present but his legacy still persists though I doubt he’d be that excited that it’s because of his botanical blunder, at least in Seattle.

A couple of updates. Apparently the bobcat returned to check on the dove nest in Tucson. As they say, “Nature in tooth and claw.”

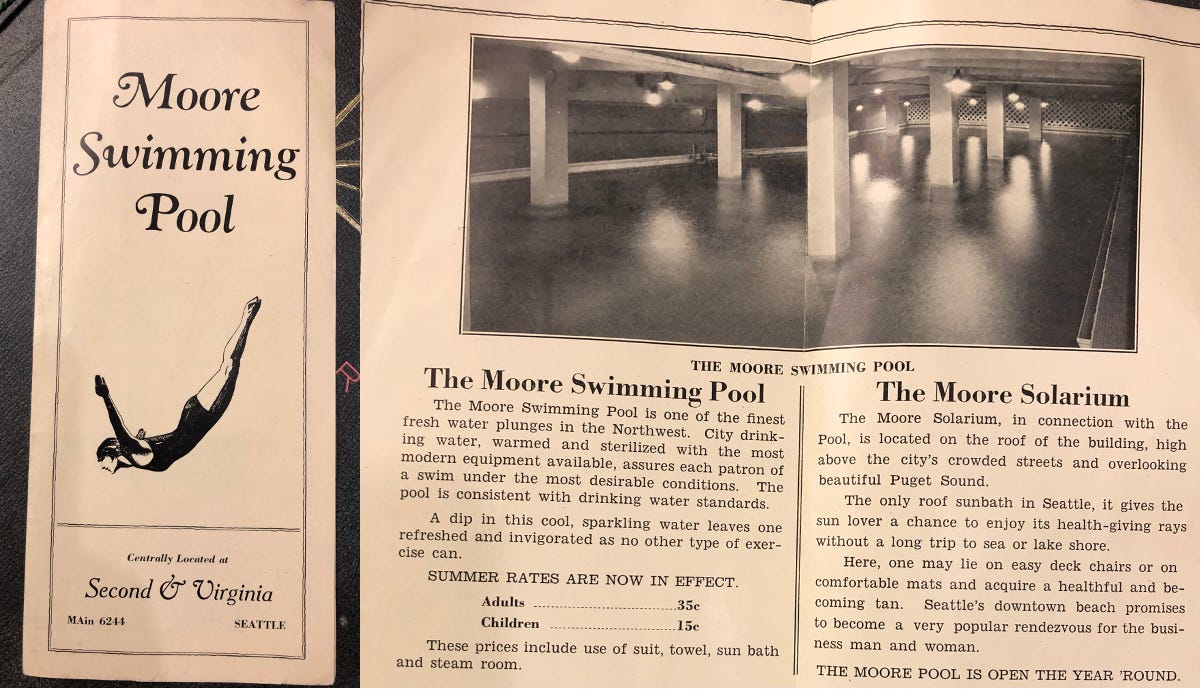

And, a friend at the Seattle Public Library sent me these outstanding images regarding the swimming pool in the Moore Theater.

Buttonwood is another name for a sycamore tree. I'm not sure what this says about Davidson's abilities as a naturalist.

Hello David - can you tell me where Nodule Point is - on Whidbey? and what are the 'cool rocks' - Are they 'concretions'? Many thanks, ellenleggett@gmail.com