I have to admit, I am rather intrigued by George McClellan, the Civil War general and non-locator of passes through the Cascade Mountains. At the time of his geographical blundering in the PNW, McClellan was a captain and part of a federally-funded mission to scout a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. In April 1853, Washington’s Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens had written McClellan what turned out to be somewhat ironic note: “We must not be frightened with long tunnels or enormous snows, but set ourselves to work to overcome them.” McClellan arrived at Ft. Vancouver on the Columbia River on June 27 and left on July 18 with 65 men, including a geologist (who wouldn’t want one on their expedition?) and 173 horses, described as mostly indifferent, and mules, considered excellent.

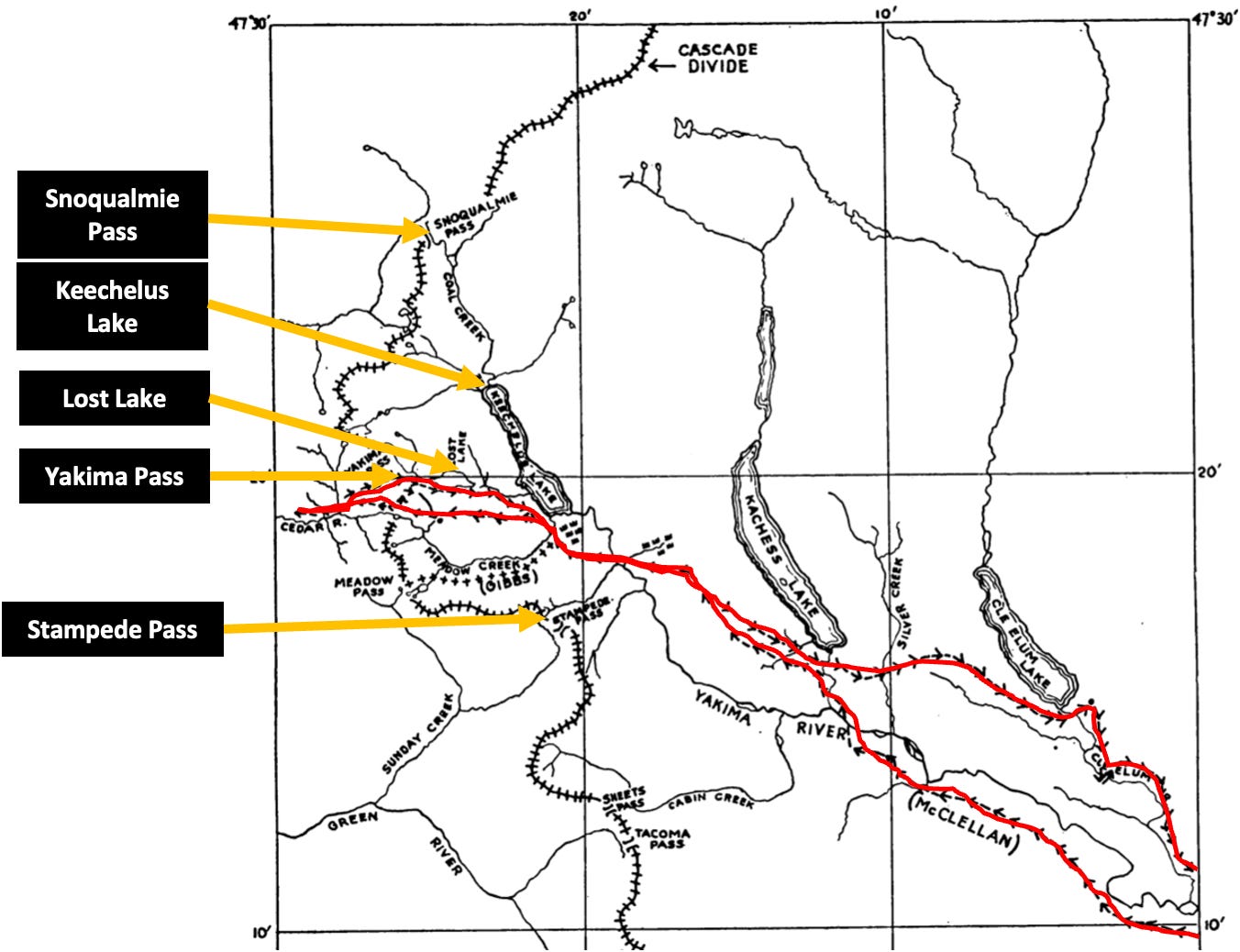

McClellan reached what he thought was Snoqualmie Pass but was actually Yakima Pass, the route of an old horse trail that came up from Keechelus Lake, on September 8. He had traveled north from Ft. Vancouver, east around the south ends of Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams, at the sluggish rate of about five miles a day. McClellan ruled out the pass as impracticable for a railroad; the route was too steep and the snow too deep. He had not actually seen any snow but heard from his Native guides that it could be 20 to 25 feet deep, and despite Stevens’ warning, the snow frightened McClellan.

Stevens, whose arrogance, ignorance, and racism sadly typified the era, trusted neither McClellan nor his source. He wrote in his official report: “The Indians cannot be competent witnesses as to the snow being six or ten feet deep in one place, or twenty to twenty five feet in another, lying in their lodges as they do all winter.” Of course they were correct; they had been exploring and visiting the mountains for thousands of years.

We now know from more than a century of records that snow depth at Snoqualmie Pass averages about eight feet in January and February and McClellan traveled the Cascades at the tail end of the Little Ice Age, when snowfall was generally greater than at present. The colder temperatures probably led to longer lasting snow accumulations, too. Proving McClellan and his sources correct, in April 1909, when the first train went over Snoqualmie Pass, the snow was 30 feet deep and it took nine days to travel the 75 miles or so from Easton to Seattle.

During his two days near Yakima Pass, McClellan poked around a bit, initially descending west from Yakima, following the Cedar River, which starts at what is now called Twilight Lake. He then headed east, following a different route than he had used to arrive at the pass, and reached Keechelus Lake. In his official report to Congress he wrote of looking to the north: “As far as the eye can determine, there is no possibility of effecting a passage in that direction; and there certainly is none between this and the Nachess Pass.”

And yet, his guides had told him of a foot trail that continued from Keechelus over what modern travelers know as Snoqualmie Pass and descended to Snoqualmie Falls. McClellan declined to investigate; he would have had to walk only three miles from Keechelus up a moderate incline to reach Snoqualmie Pass but was “pretty well tired after our 2 days divide walking, slipping, and climbing.” Adding insult to ignominy, in March 1881, Virgil G. Bogue, James Gregg, Andy Drury, and Mattew Champion became the first non-Natives to locate Stampede Pass, about five miles south of Yakima, and in 1887, the location of the first train over the Cascades. Oh George!

I still like McClellan. (And, have written about him before.) He was a surprisingly good artist and decent writer, who clearly appreciated the Cascade landscape. He also was good naturalist. He regularly noticed the geology, kept a list of plant names, and determined the snow depth at Naches Pass by marks on trees. He tried his hand at fishing Keechelus “but the wretches would not rise to the fly.” My favorite observation of his came from just below Yakima Pass, at what he called Lake Willailootzas and what is now called Lost Lake.

“At the E. end of the lake a large quantity of drift wood is piled up by the waves. From the appearance of the banks of this lake it is evidently at times some 10’ to 12’ higher than at present. No outlet is apparent at the E. end, tho’ the water clearly runs over there when the lake is high; but in about 300 yds. you suddenly come upon the water, which has thus far found a subterranean passage and suddenly shows itself as a quite large stream,” he wrote in his journal. Not only did he notice the driftwood, he figured out what it indicated, clearly realizing the seasonality of the situation. Bravo George!

What makes his observation even more remarkable is that if you go to Lost Lake, you can see what McClellan saw. Logs still rest on the shoreline, well above lake level, and there is still no visible outlet. At least there wasn’t when I visited it this past September. I am sure that none of the logs I saw date from the time that McClellan visited in 1853 but I still felt a link to the past and the thrill of knowing how the inner workings of the natural world persist through time and and the changes we have wrought.

One thing I enjoy about my newsletter is when it reaffirms that I am not alone in my geekitude. Here’s a note I recently received. “One small point.... Shoes do not abrade steps, it's the mineral particles on the bottom of shoes that sands the steps. Shoes are like glaciers.” If you were to lift up a glacier and examine its underside, you’d see that, like shoes, it is embedded with rocks, which are the agents of erosion. The ice has a hardness of only about gypsum or talc.

And, I’d like to thank everyone who has either renewed their paid subscription or chosen to get one. I have been pleasingly surprised by the number of people who have taken this route. Geeks, quasi-geeks, semi-geeks, and non-geeks unite!

Map is "off" slightly. During his stent on the W. side of the Cascades he and his troops crossed the Cedar river. Excuse me for pointing out the overwhelmingly obvious mistake. If you have not actually walked the land you have no room to doubt. Anyhow, take a look at Fernwood Natural Area, it still has a small selection of McCellan's road left in tact (8-10' wide, 300+ yards long). Registered King Co. park with small trails. Nobody cares about the road. I've currently pointed King Co and Muckleshoot/ Snoqualmie bands to this location. Good luck.

I love the "shoes are like glaciers" comment! Thank you for providing a sharing point for such details.