Last week, I had the pleasure of writing about cattails. Now, I turn to a less favored plant, at least in the horticultural community: horsetails (Equisetum arvense). (It wasn’t until I started writing this newsletter that I made the connection between Equus, the genus for horses, and Equisetum, the genus of horsetails. Funny how the brain works, or doesn’t.)

Notorious, and apparently reviled, for their promiscuous and rampant growth, our local horsetails are one- to two-foot-tall fingers of hollow green stems sporting a plume of wiry, several-inch-long branches. I have a good friend who will remain nameless because I don’t want to embarrass her but she loves to pull apart the branches section by section because they make such a “satisfying break,” or so she claims regarding her curious passion for delimbing innocent plants. One can do the same with the stems, which make an audible pop when separated.

Like cattails, horsetails (not always E. arvense, but other species in the genus) have long been culturally important in the region. In Erna Gunther’s Ethnobotany of Western Washington, she writes of Klallam, Makah, Quileute, and Quinault people eating the young stems, often one of the first green shoots to sprout. They would also eat the little bulbs on the root stock, cooking and mixing them with whale or seal oil. But ethnobotanist Nancy Turner warns that E. arvense is known to be toxic to horses so “never eat the green vegetative shoots.” Swinomish informants also told Gunther of using the plants with dogfish skin as sandpaper, as well as to polish arrow shafts.

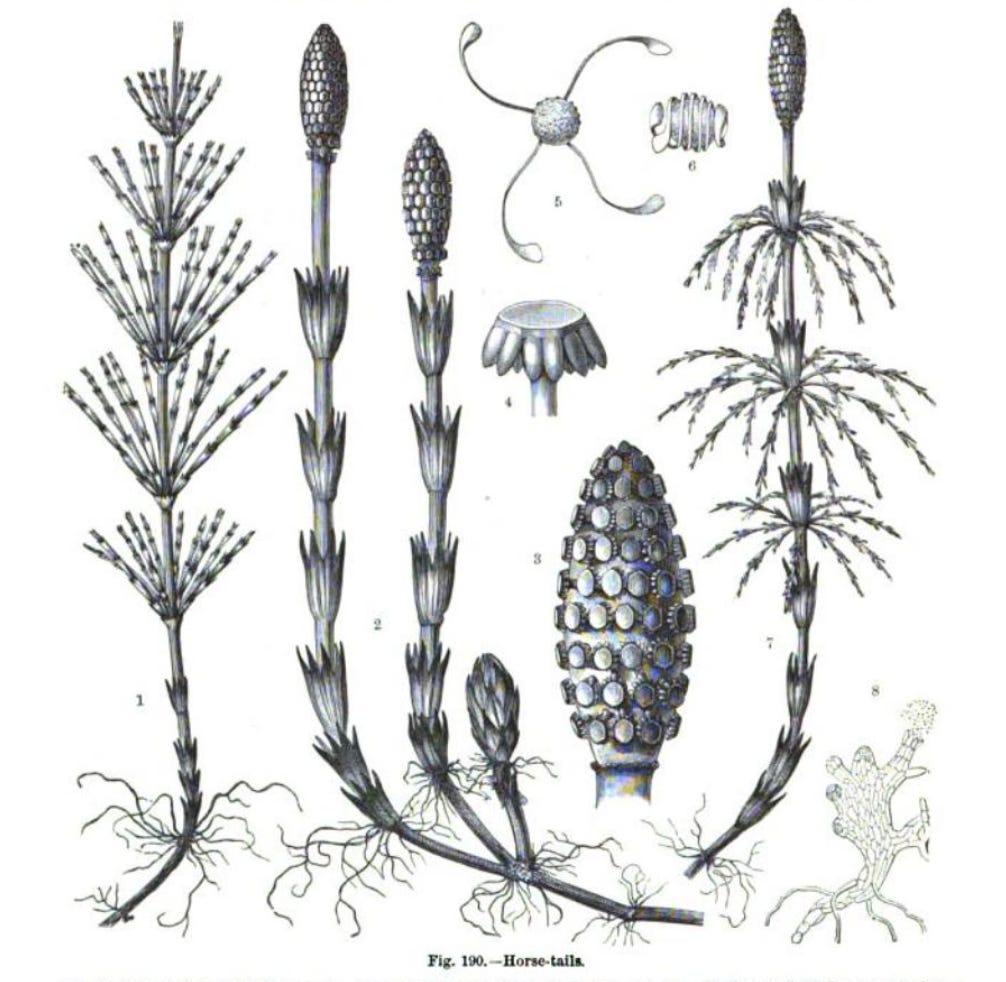

Read up on horsetails and you generally come across two statements such as these. “Horsetails have been around since the time of the dinosaurs.” “Horsetails were ginormous and towered taller than a nine-story building. The first statement is correct as Equisetum were around during the era of dinosaurs, having evolved around the same time as the big beasts, in the Triassic. According to Dr. Andres Elgorriaga, one of the leading researchers on Equisetum evolution, it is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, genera of vascular plants on Earth. What makes them particularly stunning, he told me, is that the genus Equisetum has changed relatively little since their initial evolution and still possess an extensive rhizome system; hollow, aerial stems with minute leaves fused, forming a sheath; “jointed” non-woody stems with a telescopic type of growth; and terminal reproductive structures named “strobilus.”

But Equisetum weren’t terribly tall. Back in the Carboniferous (359 to 298 mya and named because of the coal deposits from this period), when there was more atmospheric oxygen than in our modern world (except during the 1990s heyday of oxygen bars), some horsetails were the trees of the day and would have dwarfed all dinosaurs. They were not, however, Equisetum but Calamites, a close cousin in a different family. (I know I’m splitting horsehairs but what do you expect from me?)

Another long-popular, but incorrect, attribution about Equisetum is the plant’s ability to accumulate gold in their stems. In the late 1930s, Slovakian researchers reported gold concentrations in Equisetum between 3,500 and 6,100 times the plant’s substrate. Ever since, scientists, naturalists, and prospectors have perpetuated the idea that there’s gold in them thar horsetails. A 1981 report noted that horsetails grow on auriferous mine tailings and are often the only species present but the authors concluded that Equisetum actually indicated arsenic, so like many a claim about gold, it’s useless. Equisetum do though accumulate silica, which gives them another common name, scouring rush, though you, dear readers, know better that they are not a rush at all. They are, though, effective cleaners.

Like cattails, horsetails prefer moist soil, and are generally found growing near seeps. At least, that’s where I think of seeing them in the Seattle area. (I previously wrote about devil’s club and seeps.) Many people, however, think of Equisetum as a yard miscreant, a plant that pops up in their well-tended garden space, bullies out their preferred plants, and becomes a floral menace. I appreciate that concern but when I see Equisetum, I can’t help but rejoice, thinking that these plants have persisted for hundreds of millions of years doing what they do. Why should we be so dismissive, disrespectful, and down right nasty to them? In the long run, what we do will not make much of a difference; Equisetum have faced far worse than us, having survived the biggest mass extinction ever on Earth, 200 million years ago, as well as the one that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs, 65 million years ago. I am sure that Equisetum will be here long after the last gardener.

Thanks to Dr. Andres Elgorriaga for providing information for this newsletter.

And, in case you wanted a connection to the real Equus, here’s a link to a story from 2021 about Seattle’s horse powered past.

Regarding the well named horsetail trees Calamites (as you point out) my wife's uncle and USGS geologist Reuben Ross once told how Welsh miners feared encountering them on a coal seam. Pointing out the tapered stem and the "pop" of horsetail's sectional growth, he'd note how it meant that unlucky miners deep underground sometimes cut through a still vertical section of tree-now-turned-to-coal that would- after its 200million year delay- fall like a stone pile driver on unfortunate miner below. I remember Dr Ross remarking on how miners were injured and sometimes killed by falling trees "alive when dinosaurs roamed the swamps."

Think about that next time as you try to avoid dead, standing trees for a forest campsite. Indeed those ancient, dead but still standing horsetails can be considered the world's first "widow-makers." Talk about an aptly named Calamity!

Growing up in Minnesota, we used to call them puzzle plants... since you could take them apart and put them back "together." Times were simpler back then... and we found ways to entertain ourselves outside primarily.