Helpful Devil

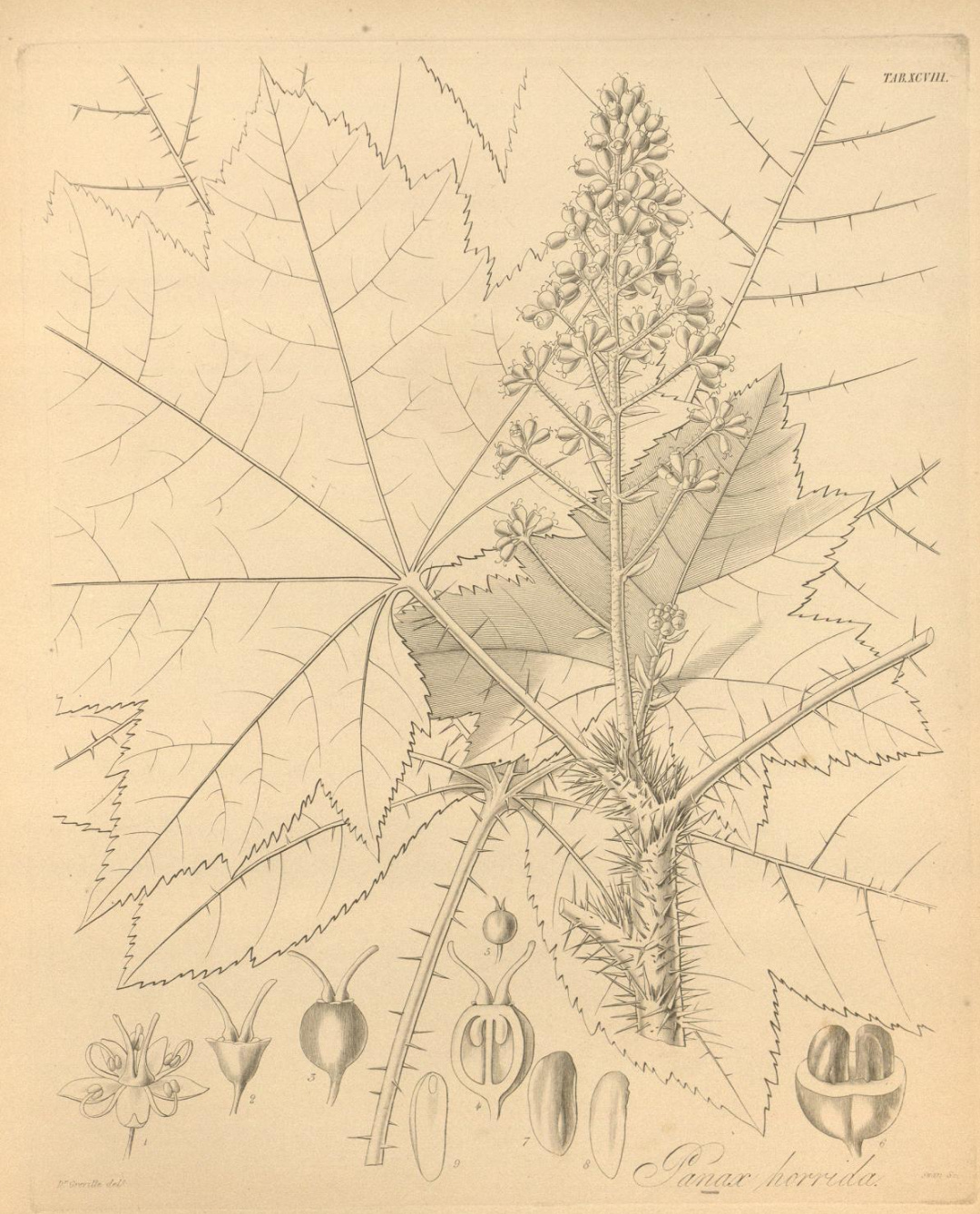

Two weeks ago, I wrote about a particularly unwelcome and spiny plant: holly. Today, I want to highlight an equally prickly plant but one long favored by people of the region. Armed with spines up the main stem and out side stems to and under the maple-leaf shaped leaves, devil’s club is one of the more formidable and intimating plants of the understory. (Just to be clear, in the botanical world, prickles, spines, and thorns are different. As my friend Sarah Gage wrote in a fine column: “broadly speaking, spines derive from leaves, prickles from epidermis, and thorns from stems.” So, there you have it, and now I am going to ignore the definition and mix the terms.)

The plants also have lovely flowers and brilliant red berries, eaten by birds and relished by bears. One study in Alaska found that black and brown bears collectively can consume more than 100,000 devil’s club berries per hour. And, since we all know the answer to the eternal question about what bears do in the woods, these meals end up spreading more than 518,000 seeds per square mile every hour, which are then further dispersed by “scatter-hoarding small mammals.” The authors concluded that bears were uniquely important in the distribution of devil’s club. Botanists refer to this fecal-based system of seed dispersal as endozoochory. I, of course, encourage you to try and drop this word into a conversation today.

Bears, sadly, are not responsible for the distribution of devil’s club in Seattle. As you might suspect with me and my interests, geology bears that responsibility. (One of the pleasures of English is being able to use bears twice when the words have absolutely no etymological connection.) The plants prefer moist areas, such as seeps, and most of our seeps result from the interplay between two layers deposited during the last Ice Age. If you cut open any hill in Seattle, you will find the lower 1/3 to 1/2 consists of clay. The next 1/3 to 1/2 of the hill is sand and silt, topped by a thin layer of till. When precipitation falls, it percolates through the till and sand until it reaches the impermeable clay and follows gravity and emerges as a seep, which means devil’s club were once far more widespread in Seattle. I still know of several locations where they grow, thanks to the many seeps that we have yet to kill with pavement.

Despite the prickly spines—or because of them—devil’s club has long been used by Indigenous people. A 1982 paper by ethnobotanist Nancy Turner describes dozens of traditional uses that addressed the physical and spiritual realms of medicine, as well as uses for fishing and as a pigment. Swallowed, chewed, rubbed onto the body, infusions and decoctions have been used for pain relief, arthritis, diabetes, stomach ailments, skin disorders, colds, and fevers, to name a few of the dozens of treated ailments. It could also aid in gambling, protect against witchcraft, work as a love charm, and provide luck in hunting. Few plants were and are as valued.

Turner further found that almost every Native language where the plant grew had its own distinct name for the plant. The translated names include big thorn, bear’s berries, codfish lure plant, prickle-big, and gambling sticks.

The first non-Native known to collect the plant was the inestimable Archibald Menzies, who obtained specimens at Nootka Sound in 1792 (actually in 1787 or 88, see follow up post). His specimens were labeled as Aralia erinacea, an indication of the plant’s inclusion in the same family (Araliaceae) as ginseng. They have also been designated as Fatsia horridus (a derivation of the Japanese word for eight, in reference to the leaves’ eight lobes) and Panax horridum but are now known as Oplopanax horridus.

As with many plants, the common and scientific names tell as much about the namers as the plant itself. The common name (another one was devil’s walking stick) appears to have been first used in the 1870s, often accompanied by such qualifiers as vile plant, most offensive plant, and hateful thing, and supplemented with complaints about getting pricked by the spines. The scientific name is a curious mix. Oplo is from the Greek for weapon or shield. Panax is also of Greek origin, meaning all healing, such as in panacea. Thus, we have a horrible, all-healing weapon, which I guess could also be read as a horrible shield against healing, though that’d be completely wrong. No wonder I like names and their origins.

One additional thought. Apparently the devil, or those who appropriated his moniker, got around. There are hundreds of places named for the prince of darkness, from the Big Devil Bayou in Texas to the Devil’s Washbasin in the Goat Rocks Wilderness (at least we know that some people thought the big baddie was concerned with cleanliness). I assume that many are quite beautiful and enchanting places so why do they merit a reference to beezlebub? It seems that if you didn’t like the guy (or whatever/whoever it is), you’d want to avoid honoring him by placing his name permanently on a location but as I have written before place names have often been used as an honorific for no good reason.

I totally remember Devil's Club growing up on the Peninsula on the interior Puget Sound side.

And not to be the bearer of bad news, but we must also remember that Native Americans were called "Red Devils" (meaning demons, not "the Devil") by the European immigrant settlers . . . so many places (such as the Devil's Canyon or the Devil's Tower) may be referencing Native Americas and special or sacred places to Native Americans. I choose to, instead, reflect on them in a more animist way, and consider these places sacred

Thank you for what you do.

I should have known you were intentional with your dual use of "bears." I had to read the sentence about geology 3 times before I understood it. And then I was starting to criticize your choice until I read your comment. You are so mischievous!

I WILL use endozoochory tonight as we are playing Wingspan. I'm sure it'll come up!

Question: I've always wondered when I see ethnobotany notes about how natives used plants medicinally - does it it mean it IS effective?. I'm guessing it sometimes is true, sometimes not, and/or maybe just not scientifically verified. Thank you.