More than happens in most cities in the United States, Seattleites regularly feel the influence of geology. Driving our glacially carved hills; worrying about an earthquake from one of the three tectonic zones of weakness that underlie the region; paying for a new seawall and SR-99; or enjoying the views of the surrounding mountains: as my wife tells me, geology did that. And, yet, unlike cities such as Portland, New York, and Denver, Seattle has very limited rock at the surface. I am okay with this.

What surface bedrock that does exist is here because of the Seattle Fault Zone. Running from Issaquah west to Bainbridge Island, the SFZ is 2.5 to 4 miles wide and has been active for tens of millions of years, slowly thrusting up rocks from the south. The most recent rupture hit about 1,100 years ago and pushed rocks on the south side of the fault up about 20 feet. In the past 10 to 15 millions of years of movement, there has been an estimated six miles of vertical movement between the uplifted and down-dropped side of the fault, which has brought old, hard rock to the surface.

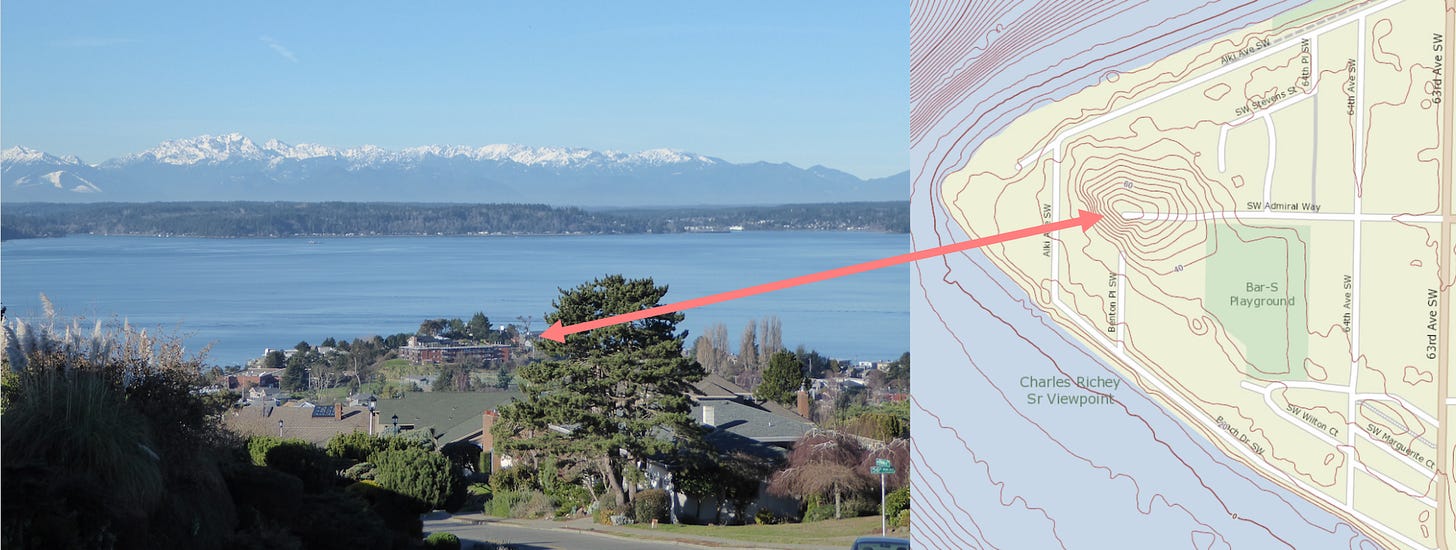

One way that this plays out in Seattle is via several topographically anomalous hills. Two are found in the Duwamish River valley east of the river and two west of the river. Another is at Alki Point. You can also see the old rock creating a topographic high west of Seward Park, too, on the map above, but I am not heading there today.

My guess is that the Alki anomaly is the most unnoticed, rising just 75 feet above the surrounding land. I know that I failed to recognize its elevation for many years but once I did, I realized the upright oddity of the summit; all of Alki is basically a featureless sand flat and is defined geologically as beach deposits, except for this curiosity knob. To geologists, it is a lump of 23-million-year-old turbidity current sediments called the Blakeley Formation, which most likely used to form a sea stack, perhaps connected to land by a tombolo. (Dang, how often does a geogeek get to write tombolo and turbidity in the same sentence? Clearly not enough!) At low tide, you can also see the Blakeley as it continues south of Alki Point, part of the reason for good tidepooling in this area.

The Blakeley also forms the two hills west of the Duwamish River in the South Park neighborhood. Unlike the rest of the Duwamish River valley and its relatively flat land, which consists of young (post Ice Age), horizontal river deposits (it’s also an area highly susceptible to flooding), the hummocks rise to 110 feet. Another idiosyncrasy is that unlike many of the Seattle hills, which tend to be steepest on the east and west sides due to glacial carving, the higher South Park knob drops precipitously on the north. For those parties interested in this abrupt ascent, two stairways (85 and 114 steps) climb the west mound.

The most accessible and most interesting mound—Duwamish Hill Preserve—rises on the banks of the Duwamish. Protected and planned by a public and private partnership, the Preserve has a short trail with steps to the summit and many interpretive signs (the area’s isolation may lead some to want to visit with others and not alone). I have also read that the knoll provided a vantage point for Native inhabitants to see who was coming and going in the valley. In case you are interested, and I know you are, the rock consists of sediments (the Tukwila Fm.) mostly deposited near a volcanic area 42 to 50 million years ago.

In her 1947 memoir, early Seattle resident Sophie Frye Bass wrote: "Seattle's hills have been its pride and they have been its problem; they have given the city distinction and they have stood in the way of progress." Sophie was referring to the infamous Seven Hills of Seattle, and may not have even known of these little geo-anomalies, even though her grandparents, Arthur and Mary Denny, had landed nearby in November 1851 and became some of the founders of Seattle. Sophie strikes me as an inquisitive sort so I like to think she would be proud of these hills, too, or at least tickled to know their origins.

Words of the week - Tombolo and Turbidity Current - From the Italian for mound, a tombolo is an isthmus connecting an island or sea stack to the mainland. A tombolo may disappear during very high tide events. Turbidity currents are fast moving, underwater floods of sediment. They are common in deep marine environments.

And, if you are interested in seeing me speak or go on a walk or want to hire me to give a talk or lead a walk for your group, here’s a link to my website.

Are all rocks in the area roughly the same age? Granite vs basalt?

I love this post thank you. I've been to, over or around these formations a number of times on bike rides but will henceforth view them differently.

As a young rock climber living in Seattle I quite resented the absence of exposed rock. Being surrounded entirely by gravel was frustrating. Nowadays, being able to go tread on some 42 million year old volcanic sediments is nearly as exciting. I mean... how far down does the formation go? It must be, after all, the "tip of the iceberg". And these pairs of formations... because the Duwamish used to flow between them?