"Seattle's hills have been its pride and they have been its problem; they have given the city distinction and they have stood in the way of progress," wrote Sophie Frye Bass in her 1947 memoir, When Seattle Was a Village. As the granddaughter of city founder Arthur Denny, Bass was in a good position to witness the early history of Seattle and her book is often credited with popularizing the romantic notion that Seattle was built on seven hills, just like ancient Rome. (Of course there’s a list of seven hills cities.)

During my more Seattle-centric youth, I liked the sound of this topographic claim; I thought the comparison gave my hometown an air of distinction. As I aged and became more skeptical, I began to question the fact—hills are everywhere—and wondered if some early day marketer had invented the idea. Many years ago, I decided to try and verify the information. Had I been misled as a youth or did we share this hilly quirk with that other city well known for its espresso? And, now that I had a geology-biased world view, I wanted to know why the city looked like it did.

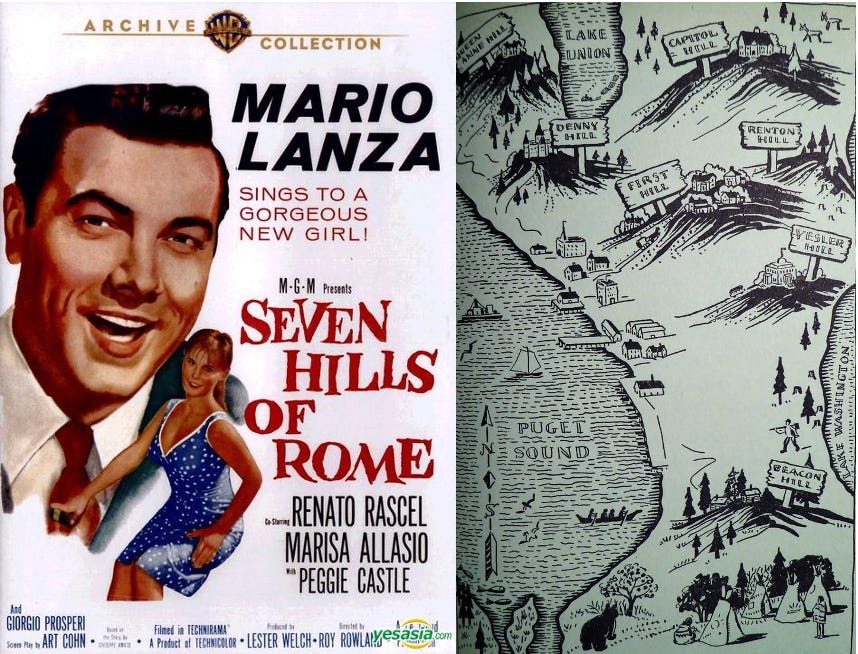

My initial task seemed simple, what constitutes the hebdomad? My friends and family said they had heard the claim but few agreed with Sophie. She listed Beacon, Capitol, Denny, First, Queen Anne, Profanity, and Renton. Sophie's first five made most lists but only my mom had heard of Profanity and Renton, also known as Yesler and Second, respectively. Some pinned their hopes on Magnolia and West Seattle, but others favored Mount Baker Ridge, Phinney Ridge, Sunset Hill, or Crown Hill. One overachiever even declared that Seattle is blessed with fifteen hills.

I also talked with someone who questioned the entire debate on the hilly septuplets. Brewster Denny, who my father worked with at the University of Washington, was Arthur Denny's great grandson. He expressed a good natured bias toward his Aunt Sophie and told me, "I don't see what the controversy is, Sophie was right."

Whether right or not, Aunt Sophie was not the first to call attention to the hilly heptad. Newspaper writers in the 1890s were noting the hills, though they liked to boast that Seattle with its “seventy times seven hills” out-hilled Rome. By the early 1900s, writers had narrowed their ambition down to seven but still highlighted the connection, such as "From a thousand points in the city, that like ancient Rome was founded on seven hills…" References to Seattle's topographical plenitude continued as the city grew but few people ever designated the mythical seven.

Instead, several moaned about the problems associated with hills. At least two engineers called for escalators to carry people and beasts up the slopes. Legendary City Engineer Reginald Thomson also had a skewed view of the topography. "Looking at the local surroundings, I felt that Seattle was in a pit, that to get anywhere we would be compelled to climb out if we could," Thomson wrote in his memoirs. "I resolved to persevere to the end."

Perseverence translated to regrading for Thomson. He not only authorized sluicing away Denny but also what is now Chinatown/ID and Dearborn Street, two other mounds that rimmed the urban pit. Local newspaperman Wilford Beaton summed up the historic viewpoint on the topography in his history of Seattle, The City that Made Itself. "The hills raised themselves in the paths that commerce wished to take. And then man stepped in, completed the work which Nature left undone, smoothed the burrows and allowed commerce to pour unhampered in its natural channels."

Early citizens may not have cottoned on to romantic notions of rocky knolls offering scenic views of majestic mountains, but by Aunt Sophie's time it had become a raging issue. A letter to the Seattle Times in 1950 asking for names of the legendary seven prompted a rain of responses. Hill advocates listed anywhere between five and ten hills, including long lost favorites Dumar, Boeing, Nob, and Pigeon Point. Adding a ray of governmental clarity, the City Engineering Department officially recognized 12 hills. They included Bass's original seven plus West Seattle, Magnolia Bluff, Sunset, Crown, and Phinney Ridge.

For most modern Seattleites, West Seattle and Magnolia have moved into the pantheon of seven, substituting for Bass's Profanity and Renton. Some historians quibble with these two because the first did not officially become part of Seattle until annexation in 1907 and the latter in 1891. Despite this "technicality" and the fact that Denny has been regraded to a barely perceivable blip, conventional wisdom, now lists Beacon, Capitol, Denny, First, Magnolia, Queen Anne, and West Seattle as the Seven Hills of Seattle.

Modified from my book The Seattle Street Smart Naturalist.

October 6 - Seattle Audubon Society - 7pm - I will be talking about Homewaters. Virtual. Fun. Thrilling.

October 9 - Bainbridge Public Library - 2pm - Secrets of Seattle Geology - An in person talk about the many ups, downs, faults, and landslides of the city's geology and why that makes life here fun and interesting and a bit daunting.

Word of the Week - Hebdomad - A word derived Greek, meaning group composed of seven. In 1837, the English Romantic poet John Southey wrote in his book The Doctor, “Like the hebdomad, which profound philosophers have pronounced to be...a motherless as well as a virgin number.” I don’t know what a virgin number is but thought someone might be able to explain it. Greek also has the word heptad, also defined as a group of seven.

Thanks for the new word and for including Pigeon Point, definitely a hill. (Of course, I admit the point that it wasn't part of the official city in Sophie's time.).

I'm a fan of electric trolley buses and networks. Pre-covid, the Metro Electric Vehicle Historical Association ran tours of the trolley-bus network in July. I asked a Metro driver why the trolley system survived when Seattle eliminated streetcars about 1940. He replied that the diesel buses of that were not powerful enough to climb our famous hills. Thank you, hills.