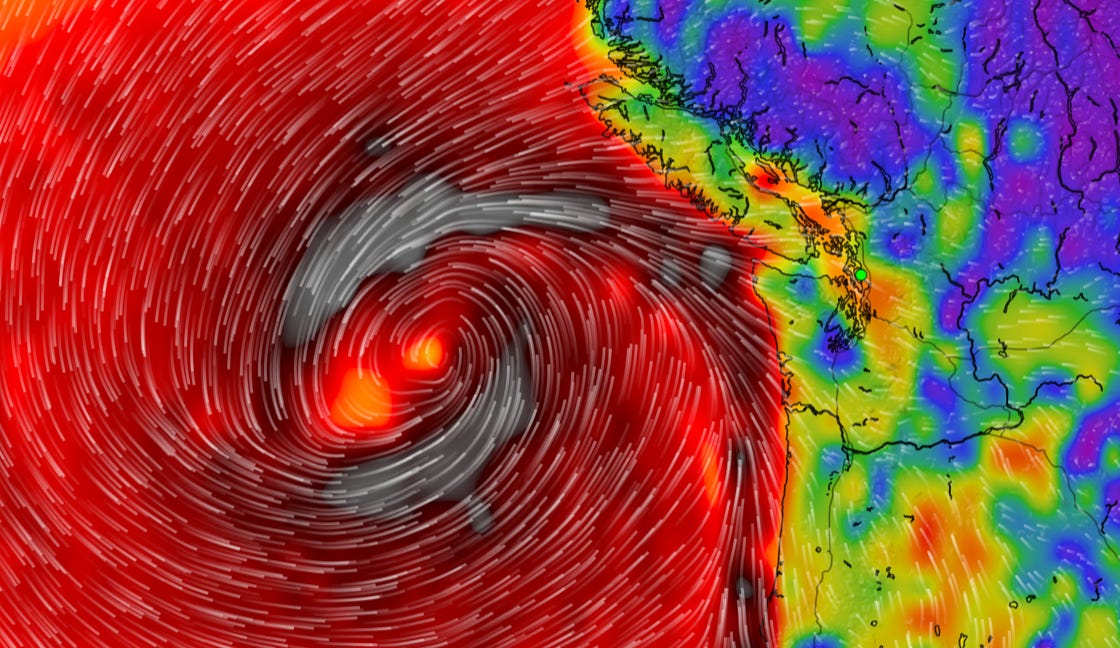

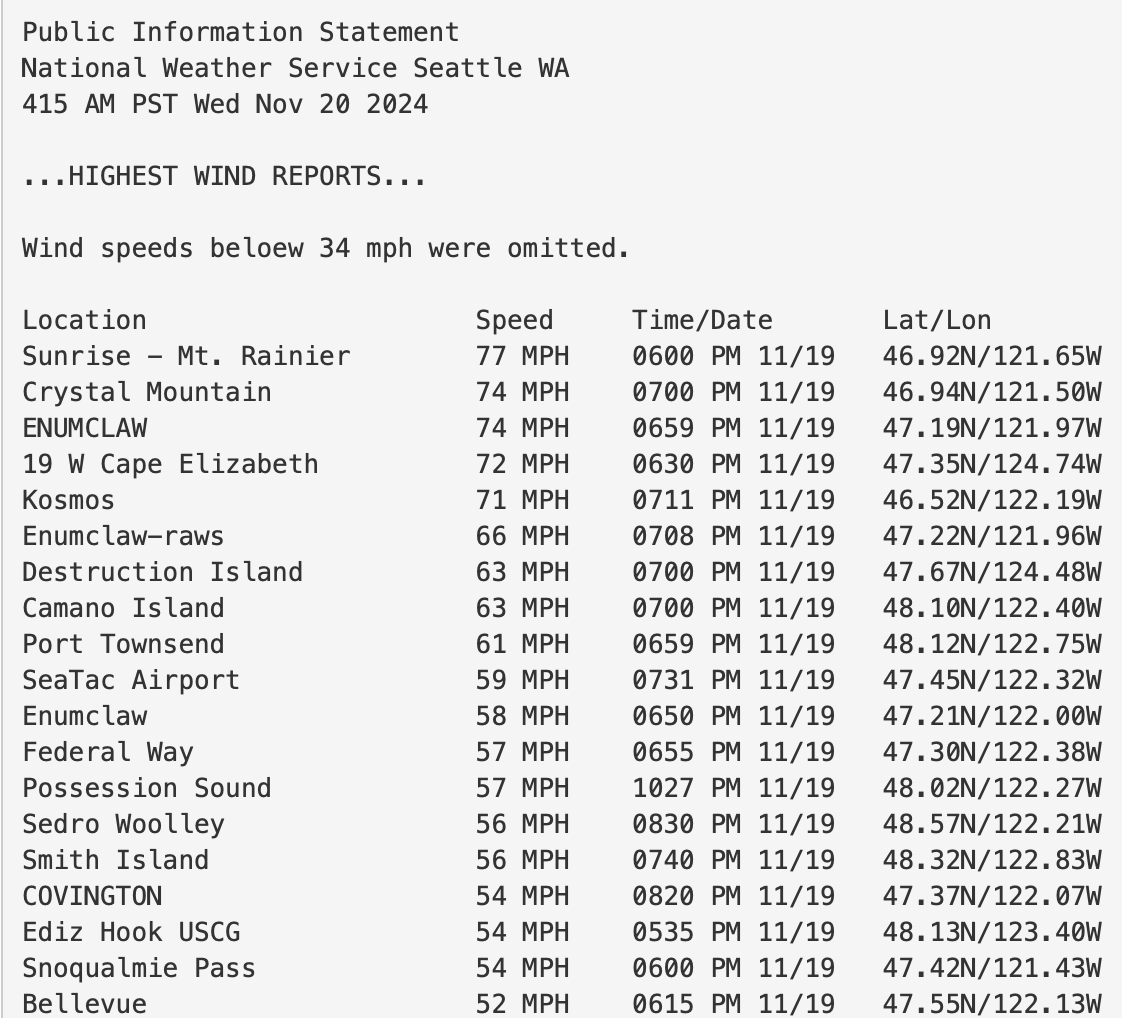

This week, we in the PNW, or at least west of the Cascade divide, got walloped with a bomb, a Bomb Cyclone to be exact. The phrase originates from the meteorologist’s bombogenesis, or a storm that rapidly strengthens in a short period of time, usually defined as 24 hours. In weatherpersonspeak, that strengthening, or intensifying, must be greater than 24 millibars, which our recent storm day easily met; it dropped (which counterintuitively, at least to non-meteorologists, actually means intensified) 66 millibars, to a record low 943 millibars, producing epic, hurricane-level winds

We were lucky at our house in north Seattle. Our lights flickered but did not go out. A huge limb fell off one of our backyard Douglas firs and hit the house but neither penetrated nor damaged it. Also falling were dozens of smaller limbs and branches and twigs and leaves, as well as a gazillion cones. Again no damages, just a lot vegetation to clean up. We also piled many of the larger limbs near the trees to create additional habitat for smaller animals, such as insects and birds. As those limbs decay they will add nutrients to the soil.

In addition to creating habitat, falling limbs benefit the trees. Better to lose a limb or many than for the entire tree to take the brunt of the wind and topple. Botanists refer to this process of withstanding winds as one aspect of thigmomorphogenesis, a splendid term coined in 1973 by botanist M.J. Jaffe. He defined it as “an adaptation designed to protect plants from the stresses produced by high winds and moving animals.” Apparently our thigmorphogenetically enhanced Doug firs did what they are supposed to: survive. Good on you big trees! (Many, many trees, of course, did fall, sadly killing two people. Downed trees also led to power outages for more than 640,000 people. But again, falling trees are essential creator of habitat, opening up the canopy and the forest floor for new species and new growth, and then feeding the ecosystem with nutrients.)

One reason our trees lost limbs, and many others toppled, is that the bomb cyclone produced an unusual wind. Instead of the normal south, or northwest winds, the wind came from the east, which meant the wind impacted the sides of the trees not used to wind and thus the limbs were more vulnerable. This wind switch occurred because of the remarkable offshore low of the bombogenetic event, which led to wind moving from high pressure in the east to the low on the west. (This phenomenon of an eastern wind is also a major driver of the infrequent big fires that strike the west side of the Cascades, such as the infamous Yacolt Burn of 1902, the deadliest wildfire in Washington history.)

Intriguingly, the east wind has a deep history referencing trouble. Numerous times in the Old Testament, the text refers to an east wind, the so-called “wind of the Lord.” A harbinger of might and power, the east wind withers plants, dries up wells, causes springs to fail, and scorches grains. East winds were also a portent of ill tidings in Victorian England. In Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, which he considered naming The East Wind, John Jarndyce, the titular owner of said house, regularly refers to dire thoughts, deceptions, and disappointments borne on the east wind. “My dear Rick, said Mr Jarndyce, poking the fire, I'll take an oath it's either in the east, or going to be. I am always conscious of an uncomfortable sensation now and then when the wind is blowing in the east.”

Joining Jarndyce was none other than Sherlock Holmes, who thought of the east wind as equally foreboding. “There’s an east wind coming all the same, such as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast,” he says in His Last Bow. But then he adds: “But it’s God’s own wind nonetheless, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.” As usual Holmes understood the true nature of the wind and that good can come out of the bad.

(This is not meant in any way to make light of the many people who suffered and are still struggling with the after affects of the storm.)

Special Offer: The University of Washington Press is offering a holiday discount on their books (which includes several of mine), if you order them through their website. The discount is 40% off and includes free domestic shipping on orders through January 3, 2025. All you got to do is go to the website and use promo code WINTER24.

Tonight, I will be giving my Stories in Stone talk for the Mountaineers Naturalist’s group about the human and natural history of Seattle building stone. There are still places available in person and virtually. Here’s a link.

Poor Enumclaw! Living in the gods’ wind tunnel.

Liked your discussion last night and just bought your book Stories of Stone.