When I walk through a downtown such as Seattle’s, I like to think that I am traveling a geologic timeline as I walk by buildings with rocks ranging in age from thousands to millions to billions of years old. Downtowns also offer a diversity of rock equal to any assembled by plate tectonics; Indiana limestone butts against Index granite, Chuckanut sandstone rests alongside Carrara marble; Italian travertine edges Minnesota gneiss.

Recently, I realized another layer to the geological thrills of the urban world. The cement used in downtown Seattle has its origins across the Pacific Ocean more than 200 million years ago. I discovered this when my wife and I visited San Juan Island.

We were lucky to see a handful of rough-skinned newts and several Juniperus maritima, a local species of juniper found almost exclusively on the shores of islands north of Whidbey Island and whose pollen has been found on Orcas Island dating back more than 13,000 years ago. (Always one who likes to be actively involved in my field work, I also tasted the juniper as a flavoring in a locally distilled gin.) All were splendid but what most excited me and gave me my new insight into urban geology were Lime Kiln State Park and Roche Harbor.

From the 1860s to the 1920s, San Juan Island was a principal lime supplier to the cement industry in Washington. Production began in 1859 with the British using beds of limestone on the west side of the island and continued through various owners into the middle 20th century. The process is straightforward. Take limestone, which by definition is a rock composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), or calcite, and burn it at high temperature, which drives off the CO₂ and leaves behind CaO, also known as quicklime.

When quicklime is mixed with water, a process known as slaking, the reaction produces lime putty, calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂). Lime putty can be used by itself or mixed with an aggregate to make mortar and cement. Because lime putty gets better with age, the Romans, who were premiers users of cement, waited at least three years to use theirs.

On the island, the kilns were huge structures made of brick and rock. Using wood, which led to deforesting San Juan and other islands, the workers heated up to 15 tons of limestone at a time to 1800°F. Within 24 hours, the limestone had become lime. Workers then collected it in barrels weighing 200 to 250 pounds and transported it to warehouses where it remained until shipping.

Several years ago, I had the good fortune to watch the making of lime at the Marenakos Rock Center. It was part of an annual gathering of rock geeks—carvers, sculptors, and stonewall builders—called StoneFest. We were taught by Irish stonemason Patrick McAfee, who helped us build a wee kiln and drive away that nasty old CO₂. As Patrick said, “We are in a parallel universe for the next four days,” as we made use of technology similar to what the Romans would have used, and which was used on a far grander scale (to what I witnessed) at Lime Kiln and Roche Harbor.

The cement boom in Seattle began after its Great Fire of 1889, when the city passed ordinances requiring stone and brick as building materials. With these ordinances, lime from the San Juans became more common in Seattle and other cities around Puget Sound for use as mortar and/or cement, as well as subsequent use of concrete for buildings and structures. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find a list of buildings that used San Juan lime but am sure that many of our earlier buildings do.

I do know though of ones that used another local lime, from Concrete. These include the old Bon Marche (4th & Pine) and Frederick & Nelson (5th & Pine, which of course prompts the “Used to be” syndrome I mentioned last week), the Exchange Building (2nd & Marion), the Hoge Building (2nd & Cherry) and the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks (which also uses aggregate from what is now Chambers Bay Golf Course).

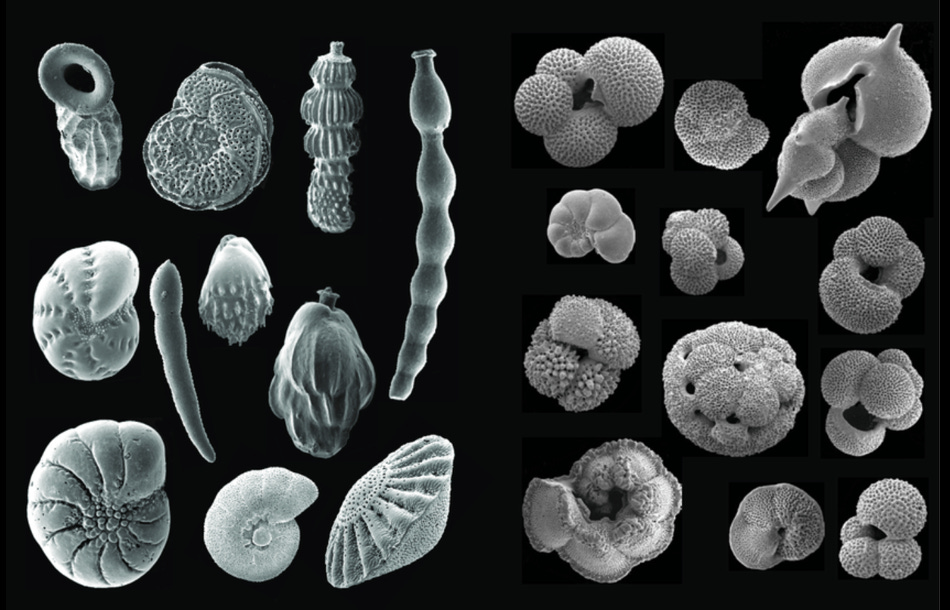

Part of what makes the local lime interesting, and adds to my joy of urban geology, is the limestone on the San Juans did not form there. Fossil fusulinids (a type of Foraminefera) from the Lime Kiln quarries indicate that the limestone formed in the western Pacific Ocean (near Asia) around 248 million years ago.

Because basalt surrounds the Lime Kiln limestone, which occurs in discrete lenses, geologists propose that the original depositional environment was a seamount atoll ringed by a reef. The basalt erupted into the water, cooled into pillow-like shapes, then tumbled into deeper water, where it was periodically covered in unconsolidated, calcite-rich, lightly fossiliferous mud, which eventually became the San Juan limestone. Millions of years later—sometime between 84 and 100 million years ago—plate tectonics carried the basalt and limestone (as part of what is known as the Farallon Plate) east and accreted, or attached, it to North America. Roughly the same geologic story also occurred with the limestones in Roche Harbor though they formed about 50 million years later.

I think that it’s pretty darned swell that the cement used in buildings around Seattle is so well traveled and so old. From Asia across the Pacific Ocean to North America, where it minded its own business for tens of millions of years, then from San Juan Island down (or up, as they would have said back in the late 1800s) Puget Sound, as well as down to San Francisco. So next time you’re downtown take a minute to appreciate the concrete and mortar in the older buildings and the lives entombed within. Their stories began a long, long time ago in a galaxy (or ocean) far, far away.

Word of the Week - Foraminifera - A group of microscopic protists (similar to amoeba) that live in the surface layers of the ocean (planktic) or on the bottom (benthic). Most forams have complex multi-chambered shells, called tests, enclosing a single-celled body. Foraminifera comes from the Latin word foramin for a hole or a window, a reference to how each test is punctuated by minute holes that allow the amoeba-like protoplasm to flow out and capture food and pull it back in.

Thanks to Darrel Cowan and Boyd Pratt for sharing geological and historical information.

Excellent piece, David. Lime Kiln Point is a great place to vist in itself, but walking on these exotic rocks adds to the enjoyment.

Very cool!