I suspect that all of us have heard, or even said, that time and tide waits for nobody, or as the great Robert Burns phrased it “Nah man can tether time or tide.” Here in my fair city, this is certainly the case, though, as I have written before, we tend not to notice the twice daily tidal changes. Some of the impacts are obvious, such as ferry schedules, water currents, and beach erosion, but as I like to do in my newsletter, here are a few lesser known and unexpected and totally cool ways that tides have played out, and continue to play out, in the Seattle area.

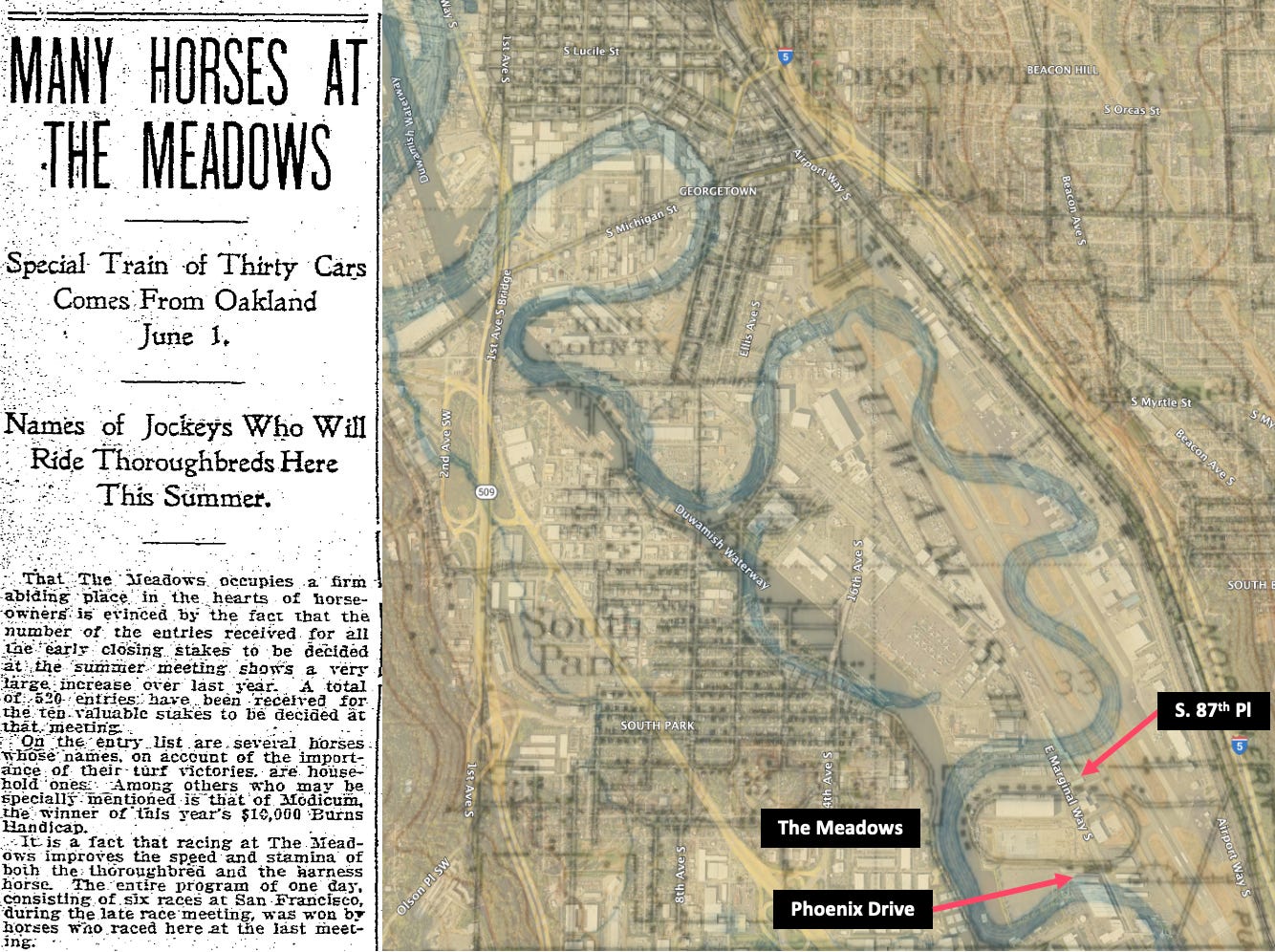

The Meadows - In 1902, Aaron T. Van de Vanter, a one time mayor, sheriff, and state senator, opened Seattle’s second, official horse track, on a meander of the Duwamish River (now between Phoenix Drive and S. 87th Place). Built with stands to hold up to 12,000 people and stables for 1,000 horses, the Meadows held races during the summer, which were so popular that people rode in special, race-day trains, basically a cattle car, to watch. One Seattle Times article further noted that nine tenths of all the automobiles in Seattle were at the track on opening day.

Part of the attraction was the speed of the track, which many considered one of the fastest in the country. One reason was its location in a bend in the Duwamish. A reporter for the Wenatchee World wrote in a February 23, 1909, article: “There is in the ground a ‘spring’ that adds seconds to the speed of the horse. The tide of Puget Sound comes sweeping up the river, and when the tide is full the speed of the track is noticeably greater, especially along the back stretch.” Even riding a “mediocre lot of horses” the jockeys broke or equaled several world’s records.

By 1915, the Meadows was basically no more, in part because of construction of the new, artificial Duwamish Waterway through the property and in part because of changed attitudes about horse racing. The location is just north of the site of Raisbeck Aviation High School.

Boeing B17 - During World War II, Boeing cranked out B-17s at an astounding pace (6,980 planes between March 1937 and April 1945). According to an interview in 2014 with Prater Hogue, who began work at Boeing in 1939, they sometimes had manufacturing issues with the planes. At Plant 3, located at the exact location as the former Meadows racetrack, workers built wing spars using a jig to create the same wing every time. Boeing also built wings at the nearby Plant 2 but the spars from the two plants didn’t always align with the template used to monitor consistency. Hogue eventually concluded, after spending nights at Plant 3: “the tide coming in the Duwamish River was affecting the floor of the Boeing plant. And it affected it enough to put those jigs off a quarter of an inch and the tide went out and changed they’d slip back and fell into place.”

I love this story but have not been able to find any other corroborating information regarding it. For instance, I reached out to the Boeing archivist and he wrote that “this story is entirely plausible but unfortunately I do not find a mention of this in the archives.” Does this mean it didn’t happen? I want it to be true but I am always a bit skeptical about memories like this. I repeat it because of the plausibility and the hope that someone else may know more.

Too Little Water - My desert-born wife has long told me that there are two issues with water: too little and too much. Even in Seattle, where it rains a bit more than in Tucson, we can see this issue in downtown buildings. The 619 Western building illustrates the too little story.

If you had stopped by in 2012, you could have seen that a crack ran down the building’s face. Like many buildings constructed along Seattle’s historic shoreline, the 619 sits atop a base of concrete blocks that cap wooden support pilings driven into the sediment. Most of the time groundwater covers the pilings, keeping oxygen away and preventing deterioration but that is only most of the time, not all of the time. Despite the 619’s location more than 250 feet from the city’s seawall, tidal water regularly creeps under the building and into its foundation and the pilings. In case you are worried, the seawall does do its primary job of keeping Elliott Bay at bay, but as the tide rises and falls water percolates through the wall, which is porous to allow storm runoff and groundwater to exit.

The issue came to light when engineers concerned that the tunnel boring machines’ vibrations might affect the troubled 619 building made a thorough evaluation. They discovered that tidal exchange caused the level of the groundwater under the 619 to vary about five feet. At low tides, this led to the wood pilings being exposed to air, which caused them to rot away and ultimately left their concrete caps floating in the ground with nothing to support them. This is not good. Construction crews eventually placed more 250 new concrete piles, in addition to giving the 619 a complete seismic retrofit, which can be seen in the massive steel beams forming X’s behind the windows on the front of the building. This is good.

Too Much Water - In contrast, in winter many buildings in the Pioneer Square district suffer from a surfeit of water. High tides combined with storm runoff and increased subterranean water movement (seeps) translate to raising the groundwater level, which then floods, or more accurately, penetrates the basements of buildings. For example, I talked to the former building owner of the Triangle Hotel (aka Flatiron Building) and he told me of a need for a sump pump in the basement because high tides produced fine fountains of water shooting out of the walls. (And, it is far from the only building whose walls gently weep.) I was also told of a nearby building where up to two feet of water regularly floods the elevator shaft at high tides.

Every six hours our local world gets a new face as the tide moves in and out. Water tables rise and fall. Buildings weep. Pilings rot. Sediment moves. Nothing too dramatic but always something changes. The tide’s tethers are strong and persistent.

I would like to thank Greg Spadoni and Ron Wright for sharing information used in this newsletter.

I worked for Boeing for 34 years, and retired in 1993. A lot of the time I worked in what they call the “B52 building”. That is the large hanger-like building parallel to the runway. The construction of the building is cantilevered. The internal walls are hanging from the roof. It was a usual thing to see a variable gap at the bottom of the main north-south wall during the day as the tide changed. Some to the old timers told me that when the B52 was in there being setup for testing back in the early 40s, they had a curious problem. The day shift would setup and level the jigs and the transits etc. (this was before the days of lasers) ready for the second shift to start the testing, but when the second shift came in, things were all out of whack. So they had to start over. Someone noticed that the problem was periodic, and seemed to be related to the tides. That was proven to be correct.

Donald Haff