Few animals struck as much fear into early day Seattleites as the “terror of the dock builder.” Although known as shipworms, they were actually clams that looked like a worm sporting a conical helmet. The clams used this shell to drill into the thousands of pilings placed along the waterfront, converting them to a Swiss cheese texture, which typically resulted in the failure of whatever the pilings were supposed to support. For example, the Seattle and Walla Walla RR trestle I mentioned last week was rendered useless in about a year because of teredo clams (another name for the bivalve) and two port commission laborers ended up in the water when a trestle-supported railroad pier they were on collapsed.

Puget Sound is not alone in harboring ravenous mollusks. For at least two thousand years, teredo clams have eaten their way through wood in salt water around the world. This was particularly so in the Mediterranean Sea, where they were well known for their ability to sink ships and inspire writers, such as the great Roman poet Ovid, who wrote: “Tis then no marvel if my heart has softened and melts as water runs from snow. It is gnawed as a ship is injured by the hidden borer.” Now that’s some misery.

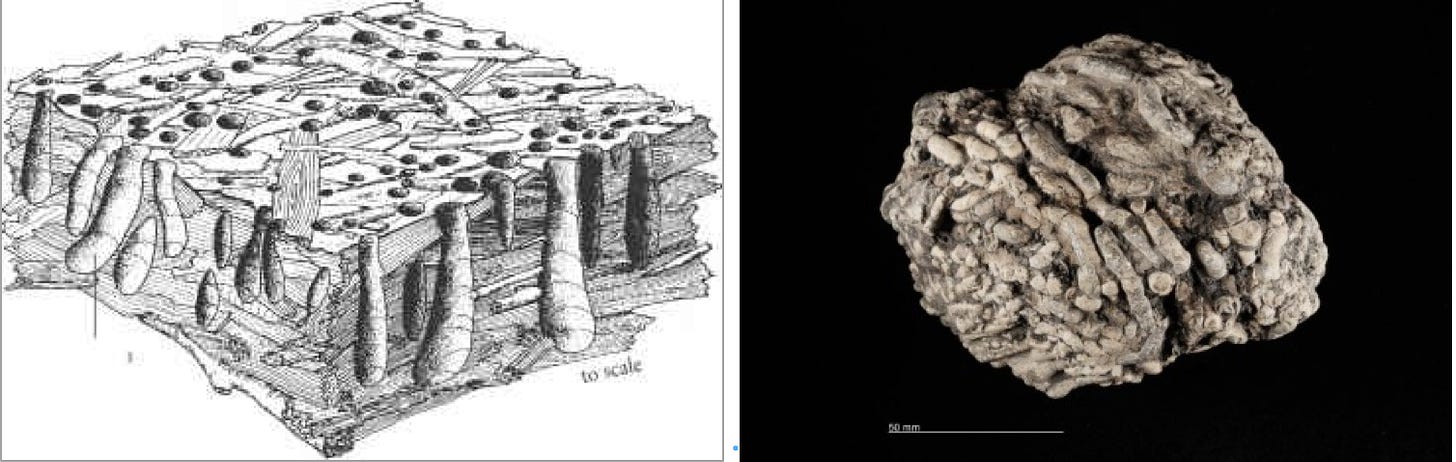

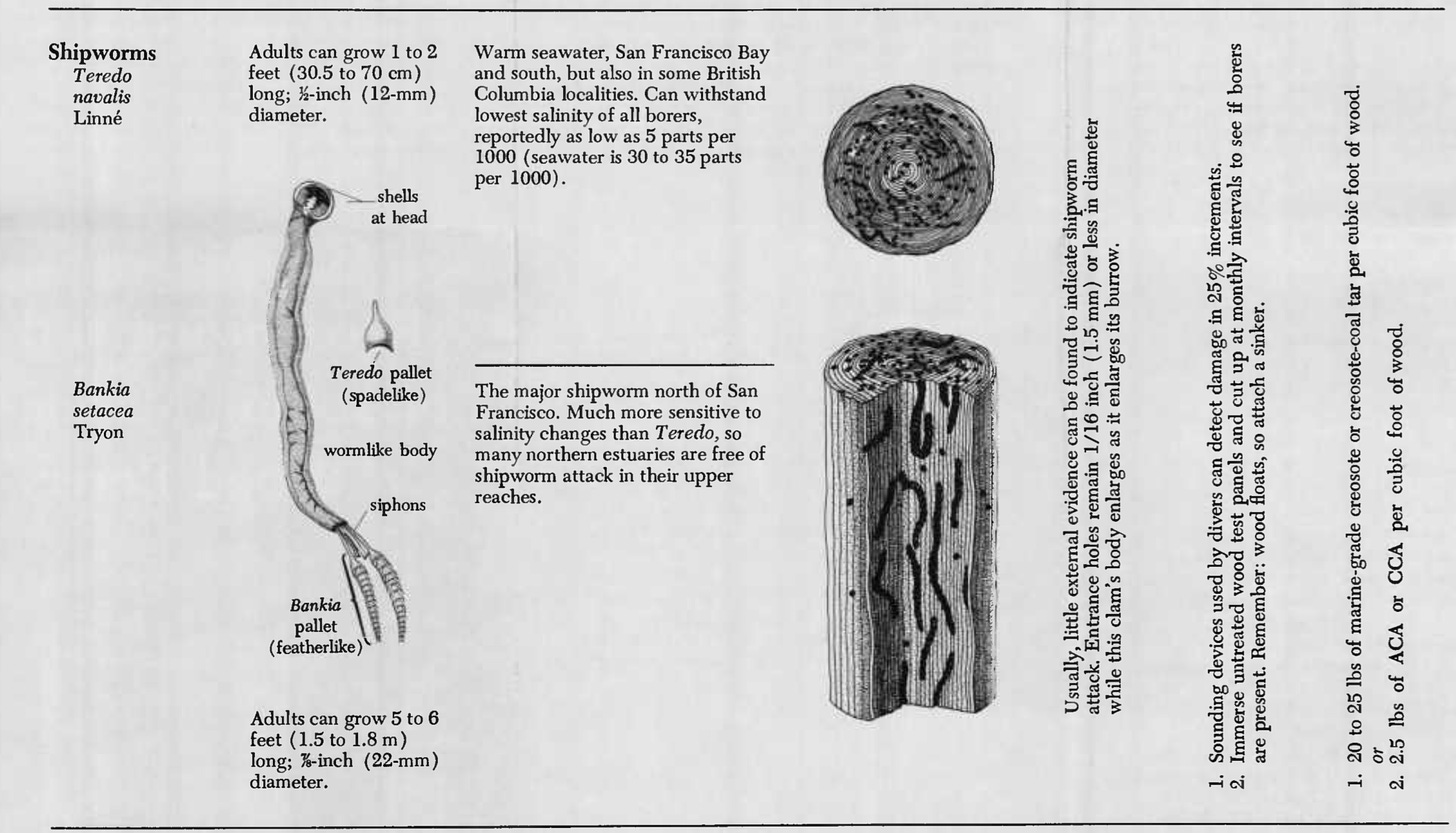

Here in Puget Sound, our species is Bankia setacea. (Another well known species is the non-native Teredo navalis, but they are generally found more to the south.) Like other clams they have minute, free swimming larvae, which eventually land on wood, only in salt water, and begin to burrow, trending parallel to the grain of the wood. Bankia can grow up to five to six feet long with a shell width of a bit less than an inch. As they burrow and honeycomb their home, they feed via a pair of siphons that extend out of their front door entry. When threatened, they withdraw the siphons and plug the hole with feather-like structures called pallets, which can tend to hide the destruction within.

Found across the Sound, shipworms were notorious for their ability to reduce solid old growth piling to a frail, ransacked log of little worth. “Led by their trusty commander, Voracious Appetite, unnumbered battalions of the Teredinidae nation have invaded Salmon Bay,” wrote a Seattle Times reporter in 1915. But not everyone disliked them; an 1888 article quoted a retired sea captain who noted how the clams helped eliminate drifting logs and floating wrecks that could damage ships. “It is a part of his business to clear the high seas of wreckage, so that there shall be fewer perils for ships and human life.” How could anyone abhor an animal so devoted to aiding our species in times of peril?

Apparently many did and they launched a toxic attack to stop the clam. Lumber mills tried soaking logs in creosote, coal tar, asbestos, castor oil, and strychnine but the poisons apparently “pleased the teredo much, seeming to act as a condiment on what must have been a rather monotonous bill of fare,” wrote a Portland Oregonian correspondent. Another method was to use pilings still covered in bark. During the growing season, workers would girdle the bark just above the base, which killed the tree, and then let the bark shrink for several months, before cutting it, and using it as a piling.

Lest you think that shipworms and other similar wood-damaging invertebrates no longer strike fear into maritime planners and engineers, dear reader you would be mistaken. Ironically, such worries are a relatively recent manifestation. During the decades when industrialization contaminated urban marine waterways, the teredo clam problem disappeared primarily because the clams couldn’t tolerate the pollution. Now that urban waters are cleaner, teredo clams have returned and the hungry bivalves have started to eat away at the old pilings.

In Seattle, we have also felt the modern influence of shipworms. One of the reasons that the city replaced its aging seawall was damage to the wood substructure caused by the teredo clams and other marine borers called gribbles. This time we avoided wood, relying on materials less susceptible to invertebrates.

I suspect that we may not ever stop the shipworms. Paleontologists have found traces of shipworm activity in 20 to 35 million year old, fossilized wood in sandstones from Puget Sound and on the Olympic Peninsula. Boring into and eating wood is clearly a successful way of life, which has persisted for millions of years and will most likely continue long into the future. Perhaps we simply need to take the long view and learn to live with these ancient terrors.

I am pleased to announce that I will be leading a series of free walks in downtown Seattle on Friday afternoon’s from 1:30 to 3pm (July 16, 23, 30 and August 6, 13, 20, 27). The walk—based on my Who’s Watching You? walk in Seattle Walks—will explore the terra cotta and carved animals and faces in downtown buildings. They are organized through Global Family Travels and the Downtown Seattle Association. Here’s a link for registration.

Plus, my pal Jen Ott will be leading a tour of the downtown waterfront on Saturdays at 10am, also for GFT and DSA.