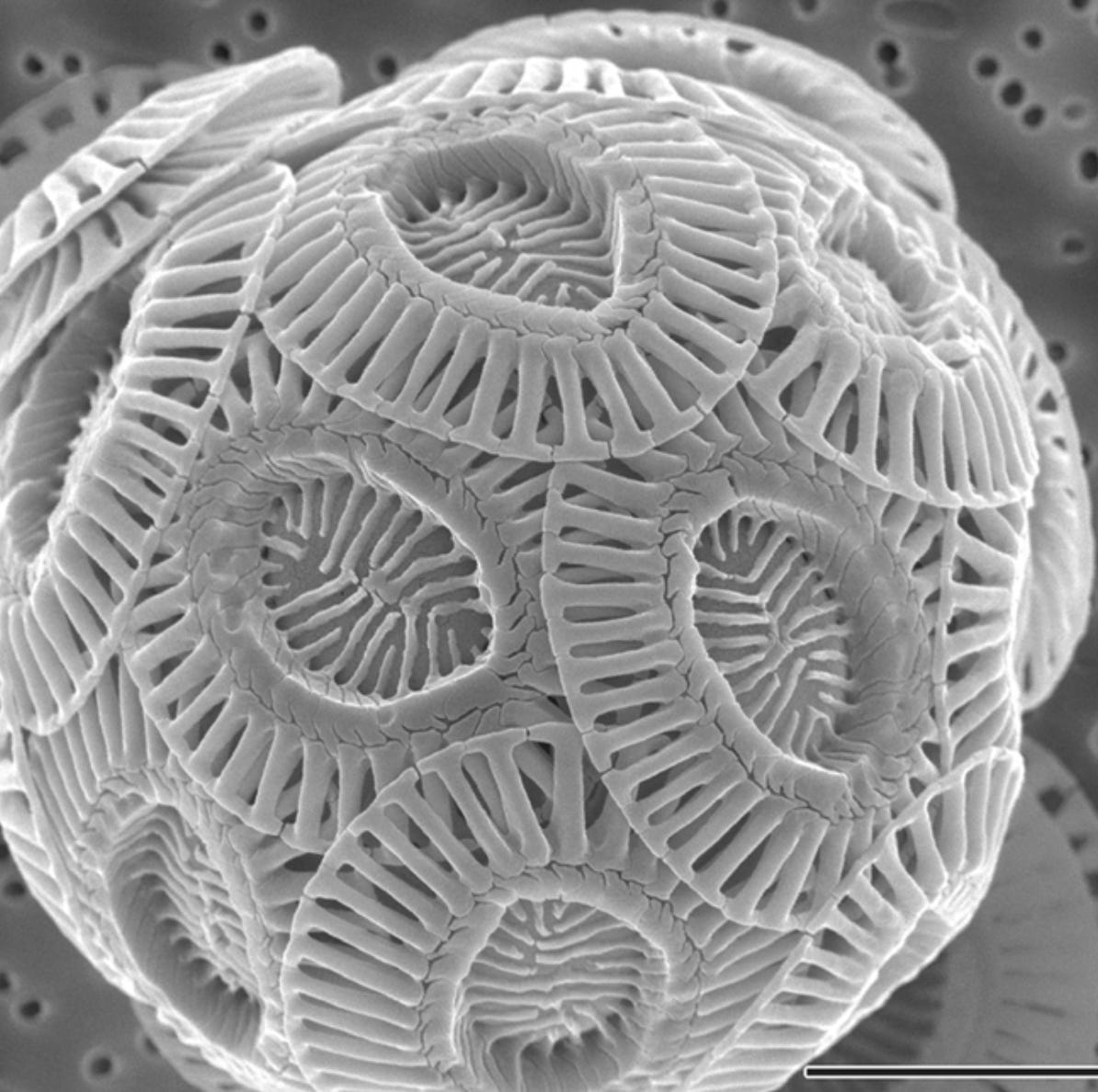

A couple of weeks ago life exploded in Discovery Bay, just west of Port Townsend. Viewed from space, the profusion of critters turned the normally blue-hued bay into a vibrant turquoise green. The culprits were billions of coccolithophores (Emiliana huxleyi, or Ehux), single-celled marine plants (phytoplankton), commonly described as photosynthesizing algae. These microscopic organisms build a protective exterior made of plates (called coccoliths) that come in a variety of shapes ranging from shells shaped like steering wheels to pig-snouts surrounded by ruffles to a hollow disc with radiating fingers.

In Discovery Bay, the phytoplankton had undergone a bloom, or what one paper described as concentrations of 1,000,000 cells per liter, science-speak for “Dang, that’s enough little beasties you can even see them from space.” Although they have occurred for tens of millions of years, these blooms are in a way a modern phenomenon because scientists are primarily aware of them because of satellites. Since the 1950s, there have been dozens—including one in Hood Canal in 2016—witnessed from beyond the realm of Earth.

As exciting as these blooms are, and they are darned nifty, what excites me is my past association with coccoliths. I like to think that when I was a child, I regularly encountered Ehux, at least at school. I suspect that many who read this had similar experiences because chalk, at least in its original form, consists primarily of coccoliths. For instance, some of the most famous chalk in the world, the White Cliffs of Dover, is made of 70 million year old coccolithophores that lived, died, and sank in an ancient ocean, forming an ooze that lithified into what became the great cliffs.

I know that the chalk I used throughout my years of schooling didn’t come from Dover but school chalk, the kind we used to write with on blackboards, is often made from limestone consisting of coccoliths. (Modern chalk is typically more gypsum than limestone but is still coccolith rich.) How totally cool would it have been to have had access to a microscope and seen the fossils at my fingertips?

Further pleasing my rockgeek heart, when we wrote with chalk, we did so on another natural substance. I am, of course, referring to blackboards, which are made of slate, a metamorphic rock. Like chalk, slate began life as mire at the bottom of the sea but instead of body parts the ooze was plain old mud. In the United States, most school slate came from Pennsylvania, from sediments that accumulated 450 million years ago and formed beds of shale. The shale was later squeezed and baked by tectonic action, which metamorphosed the soft rock into hard layers of slate. (If you play pool or billiards, you also encounter slate as it’s the base of a pool table, and why they are so heavy.) Sadly, no teacher that I remember took advantage of the slate/chalk story and told of us their geological origins.

Several years ago, while writing a book with a chapter about slate, I visited my old elementary school, where I had my first memorable encounters with slate and chalk. (Being a noisy and somewhat troublesome student, I often ended up writing on the blackboard “I will not disturb other children,” or something to that effect.) Sadly, a renovation had led to both blackboards and chalk being eliminated and replaced by whiteboards and dry erase pens.

If I may, I’d like to quote what I wrote about my visit. “As I wandered the hallways at Stevens, I couldn’t help but wonder if today’s students are missing out. Where once they could have continued the centuries-old tradition of employing fossil sea critters to write or draw on a metamorphosed slab of fine-grained marine sediment, now they write on petroleum-based, plastic whiteboards with an odoriferous, chemical-filled pen. In a society where our failed connection to nature surely has contributed to our failed understanding of human impact on the land, the loss of slate and chalk is one more example of how we are taking nature away from children and replacing it with something artificial.”

Word of the Week - Coccolith - The calcite plate surrounding the bodies of unicellular phytoplanktons called coccolithophores. Thomas Huxley coined the term based on sediment from an 1857 seafloor survey designed to figure out where to lay the first telegraph cable between England and the United States. Coccolith comes from the Greek kokos (berry or grain) and lithos (stone). In an 1868 speech titled “On a Piece of Chalk,” Huxley said: “I weigh my words well when I assert, that the man who should know the true history of the bit of chalk which every carpenter carries about in his breeches-pocket, though ignorant of all other history, is likely, if he will think his knowledge out to its ultimate results, to have a truer, and therefore a better, conception of this wonderful universe, and of man's relation to it, than the most learned student who is deep-read in the records of humanity and ignorant of those of Nature.”

Imagine what the vapor from those chemical-filled pens is doing to young brains. I had thought the weirdness of younger generations was due to social media and those who exploit them, but maybe living on fumes has a role too.

At the university where I taught, instructors can still request to be assigned classrooms with blackboards. A quick way to become "old school."