I like to think I pay attention but the other day I realized that I have been missing something interesting every time I go for an urban walk. Wherever I go, I pass by utility poles. Holding up the wires that feed our modern lifestyles, these poles may be one of the most common and overlooked pieces of urban furniture.

What we now call utility poles began life as telegraph poles, when Samuel Morse and his colleagues erected them in 1844 to transmit telegraphs from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. The wood poles soon snaked across the United States and by the early 20th century had become known as telephone, power, and utility poles. Modern estimates place the number of utility poles in the U.S. at 150 million.

The first telephone appeared in Seattle on April 8, 1878, using the wires of the Puget Sound Telegraph Company, and by the 1890s, telephone poles lined downtown streets, often towering above the surrounding buildings. We now have 91,000 poles in the city. The tallest wood one is 95 feet. The oldest were put up in 1905 and are made of western red cedar, like 73% of all Seattle poles; 21% are Douglas fir, the rest unknown.

What attracted me to utility poles was a notice from Seattle City Light that they were going to replace a pole on our street. The city has long inspected and replaced poles but began an accelerated replacement program following an April 2019 storm that toppled 26 poles in Tukwila and sent two people to the hospital. A crewmember replacing our pole told me that a northern flicker had damaged and weakened the pole. I wasn’t surprised as I regularly see and hear flickers banging their heads against the pole. (In Alabama, they spend $3 million annually to replace woodpecker-damaged poles.)

In Seattle, birds, squirrels, and lichen are major exploiters of this habitat. For the squirrels, the poles are off- and on-ramps to an extensive high-wire highway, which allows them to move quickly and usually gracefully, though I have seen squirrels struggle negotiating their tightrope travel. Unfortunately, some squirrels get shocked to death on the wires, which can lead to power loss. According to the semi-serious Cybersquirrel website, squirrels caused 1,252 outages from 1989-2019.

There is also the telephone pole beetle (Micromalthus debris), named because an early specimen was found emerging from a chestnut telegraph pole. (They have been found in Vancouver but not in Seattle.) These bugs are quite amazing; they can give birth parthenogenically and have remained unchanged, more or less, for at least 20 million years though it’s unclear how they lived before telephone poles came along.

As is often the case, lichen have adapted to a human created substrait. Examples include Lecanora conizaeoides, which began to spread widely in cities with the Industrial Revolution; Hypogymnia physodes, which has been used for air pollution studies; and Evenia prunastri, which was “ground up with rose petals to make a hair powder which whitened wigs,” wrote Frank Dobson in Lichens: An Illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species. Always glad to be able to purvey thoughtful advice for when one needs to whiten one’s wig!

Birds are probably the best known pole users. Poles function as snags, providing perches (as do wires), nesting locations, and space for drumming and food caching. When I asked on the local birding network, Tweeters, I was told of 48 pole-using species ranging in size from chickadee to eagle and alphabetically from acorn woodpecker to white-breasted nuthatch.

Unfortunately, birds plus electricity do not add up to happy birds. They are regularly killed by electrocution and shock, especially larger birds, which more readily bridge the gap around energized conductors. One study estimated 504 golden eagles annually die this way. Birds also collide with wires, notably raptors with small home ranges and ones where the wires are between the birds’ nests and their foraging locations. I am still always impressed to see a bird land on a wire; it’s a supreme act of agility.

Conscientious maintenance to address electrocution and other animal-related utility pole interactions includes exclusion netting, chemical repellants (including oil extracts of cumin, rosemary, and thyme), better insulation, increasing distance between wires and potential perches, perch guards, and hazing. Another solution, which one sees in Seattle, and many areas, is to build a platform just for the birds and devoid of wires. Seattle City Light has built several in the city, which ospreys have colonized.

Unfortunately, poles have long created additional problems because of how they are treated for protection against rot and other issues of degradation. Throughout Puget Sound are numerous old mills and other sites where companies applied creosote, which has resulted in shoreline areas teeming with toxins such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenol (PCP), aromatic carrier oils, and dioxins/furans. (This process is not the lone source of PAH’s in the Sound. They also come from combustion, such as vehicles and woodstoves.) Cleanup of these poisons is an ongoing process, and often just as overlooked as the poles themselves.

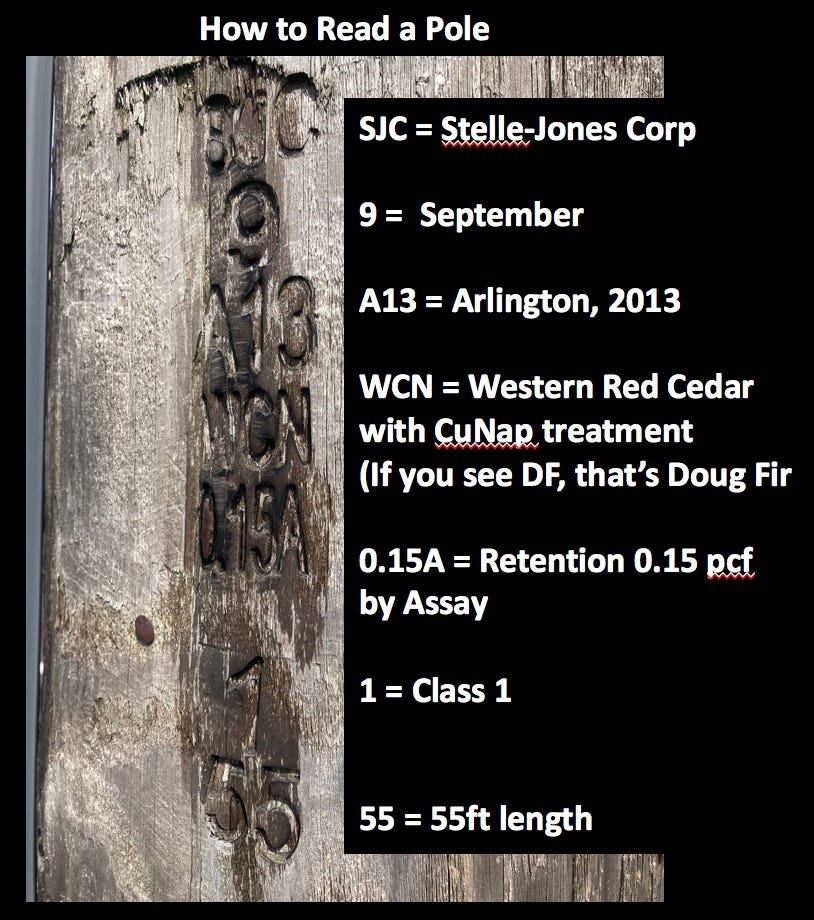

One final aspect. Next time you see a pole, check out its brand, which contains all sorts of good information.

Word of the Week - Parthenogenesis - From the Latin for virgin birth, it refers to asexual reproduction and occurs throughout the animal kingdom, including aphids, komodo dragons, hammerhead sharks, and whiptail lizards, a handsome group I used to regularly encounter in Moab. Benefits to parthenogenesis include more rapid reproduction (no annoying mate to deal with) and easier colonization of new territory but clones are more susceptible to disease and changing environmental conditions.

Thanks to Hernann Ambion, Peter Arnstein, Butch Bernhardt, Gary Bletsch, Titus Butcher, Richard Droker, James Dwyer, Duncan Eccleston, Steve Hampton, Thomas Hörnschemeyer, David Hutchinson, Michael MacDonald, Bob Myhr, Robert O’Brien, Scott Ramos, Jenn Strang, Danene Warnock, and Peter Wimberger for technical and natural history information.

Thanks David B. Always interesting. Always entertaining. Opening our eyes and awareness to our environment(s).

The following note was sent to me, which the author let me post as a comment. David

###

Thanks for the article. It was very interesting. We do take issue with one paragraph near the end concerning issues with preservatives used to treat poles. Yes, it’s true that in the early days of treating plants in the last century were less judicious with the application of preservatives. However, implying that those plants were responsible for “shoreline areas teaming with toxins” is simply not true. Take PAHs for example. You are correct they are found in creosote. They are also found in petroleum products, asphalt and a host of other materials used in industrial production that has operated for decades in and around the Puget Sound. Blaming wood treating for all PAHs that are in the Puget Sound environment is unfair and simply not true.

One thing to consider is why we pressure treat utility poles. When using wood for infrastructure, you want it to last as long as possible given the disruption in replacing them. Without preservatives, wood poles would last only a few years in service. By pressure treating poles, we can create poles that last for many decades in service, despite being exposed to incredibly demanding conditions. Preservatives are intended to keep decay and insects (and yes wood peckers) from deteriorating the wood by creating a protective barrier in the wood. Some of the preservative does move out of the pole, but it does not move far and instead become part of that protective barrier.

Attached is a report on research on preserved wood poles and their impact on the environment. It reviews preservatives moving from poles into the environment, providing context on what actually happens with poles in service.

Another thing to consider: if we didn’t use preserved wood poles, what else would we use? Many assume steel, concrete or composite plastics are without any impact to the environment. Internationally recognized life cycle science shows that isn’t the case. The attached report on a life cycle assessment, or LCA, on penta poles vs. alternative materials clearly shows preserved wood poles have a far lower impact on the environment.

One other point often neglected when discussing alternatives to wood poles – the ability to provide replacements after storms or natural disasters. The wood treating industry has an impressive record of gearing up to provide replacements and get power restored. After Hurricane Katrina, some 92,000 treated wood poles and 90,000 wood crossarms were delivered within four weeks. Whether it’s wildfires or winter storms, we’ve continued to deliver replacement poles in this region quickly to get the power back on. The manufacturing process for alternative materials makes it impossible for them to match that.

David, there are tradeoffs with any product. We understand preserved wood poles are not perfect and past practices in treating them would not be the choices we would make today. Like every industry, we’ve learned how to do things better. Our operations today seek to protect the surrounding environment as much as possible and our plants have spent millions to provide that protection. We work to place enough preservative to protect the wood while limiting the amount that can potential move into the environment. We do all of this to deliver preserved wood poles that are safe, durable, long-lasting and readily available at an affordable cost.

Much has changed in our country over the nearly two centuries since the first wood pole was used. Still, despite the many technical advances we’ve achieved, preserved wood poles are still a critical part of today’s electrical system. As we increase our reliance on electricity for our way of life, these poles will be even more essential to our future.

--

Butch Bernhardt

Sr. Program Manager

Western Wood Preservers Institute