The other day at Seattle’s Hiram M. Chittenden Locks I had a new experience. I saw a harbor seal swimming on the freshwater side of the overflow dam. Like many visitors, I had previously seen harbor seals and sea lions within the locks, where I also assumed they had ventured in search of fish, but this was the first time I had seen one dallying on the Salmon Bay side. I couldn’t tell what the animal was doing as I saw the head only once but I suspect food was the main attractant.

As I watched the seal, I realized that I hadn’t given them or their oft-mistaken-for-cousins, California sea lions, much consideration. I had seen them many times over the years throughout Puget Sound and along the Pacific Coast but hadn’t thought about the other places I had seen them, such as in coastal rivers and estuaries. I knew that they were both marine mammals, and thus animals primarily of the sea. I also knew they had evolved to make use of freshwater for short periods of time but seeing them in a lake seemed odd.

No matter the where, when, and why, it’s an amazing adaptation to be able to navigate and inhabit two such different environments; both media may be liquid but clearly both are not suited to all. As Mr. Coleridge wrote: “Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.”

From what I learned from employees at the Locks, the seals and sea lions (mostly males) regularly move between Puget Sound and Salmon Bay. They do so in two ways. The simplest, most direct method is enter the locks when they are open to saltwater, wait till the locks fill with freshwater, and exit into the bay. But they don’t need to wait, they can also travel via the feeder culverts that run along the sides of the locks and provide the freshwater needed to raise boats, and pinnipeds, from salt to freshwater. No matter how they figure it out—smell, follow the leader, or by accident—it’s another fine adaptation to place.

Despite their adaptions to humanity and our inventions, the pinnipeds sometimes get swept away by what we do. A lock employee told me that she recently saw a group of young sea lions on the freshwater side near the overflow dam, when one of them, who seemed to be trying to figure out how to return to the salt, got carried by the current through the smolt gate, which shoots water from the bay to the Sound. “I heard a little bloop sound and down he went…When I turned to see the sea lion below, his head was snapped around looking back towards the slide like, ‘what just happened?’”

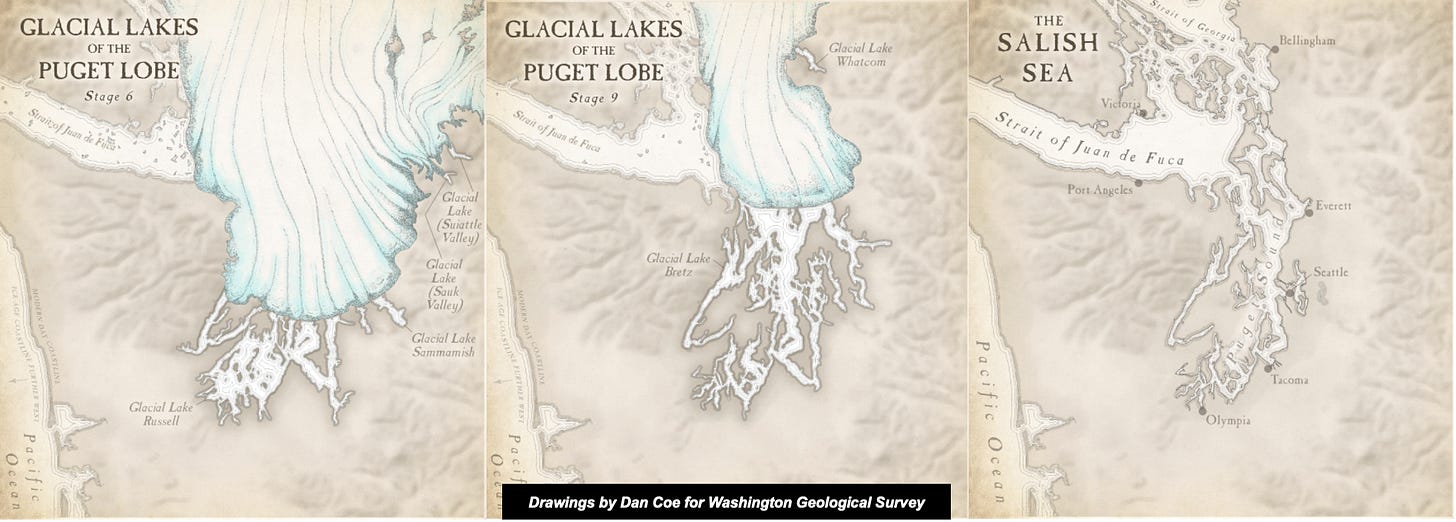

The locks are not the first time that harbor seals adapted to freshwater in the region. During the last Ice Age, as the Puget Lobe glacier melted back to the north, freshwater lakes—Glacial Lake Bretz and Russell—formed in the lowland. They existed for several hundred to a thousand years or more, until the ice retreated far enough to the north to allow saltwater to create Puget Sound, around 15,500 years ago. Genetic research shows that harbor seals may have used these lakes as an ice age refuge of suitable habitat, which evolved into a unique population of seals. Perhaps this is why they like to traverse the locks into the freshwater; they are simply playing out a life history deeply embedded in their DNA.

Two weeks ago an excerpt from a book I contributed to about Dale Chihuly and his Boathouse appeared in the Seattle Times. Thanks kindly.

While swimming near the outlet of Thornton Creek at Mathews Beach I had a surprise encounter with a seal! Pretty far from the locks. Always fun to swim with seals.

Brings to mind seals and porpoises trapped when Hubbard Glacier blocked Russell Fiord - https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/09/21/crews-try-to-rescue-seals-and-porpoises-stranded-by-glacier/11e2380d-e2ee-4258-b0a0-f30ebbfb3145/ - R Droker