Chaucer, Milton, and Shakespeare share several attributes. They are some of the rare authors typically referred to by their last names only. They regularly make the list of top ten writers in English. They held less than favorable opinions about cormorants. To Chaucer, the birds represented gluttony, to Shakespeare insatiable greed, and to Milton, he took them to a new low: “Satan…sits, in the shape of a Cormorant.” Dang.

And, these fine writers are not alone. Throughout the 1800s, cormorants were a stand-in for base behavior.

“The attempt to create a little passing political capital out of a failure of such a grasping cormorant.” Washington Standard, May 11, 1888

“A man who wouldn’t feel complimented at being called a cormorant would smile at being called a night owl.” Pacific Tribune, June 6, 1868

“The door is opened wide for the most fraudulent combinations and peculiarities of unprincipled, cormorant officials.” Washington Statesman, September 5, 1863

What did these birds do to deserve such scorn?

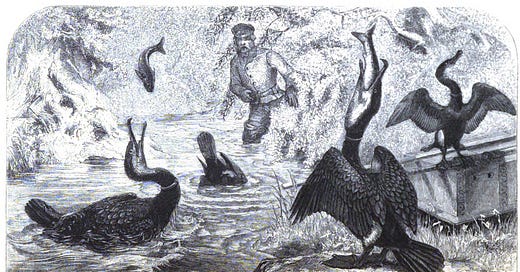

Apparently, cormorants have a propensity to do something as contemptible as eating. In particular, they specialize in fish, adeptly taking a huge variety. So skilled are cormorants’ piscivorous ways that people around the world have long (the practice dates back to 3rd century BCE China) captured the birds and utilized them for fishing. A charming description of this process comes from one of the earliest bird books, The Ornithology of Francis Willughby, published in 1676. (Plus you learn the origin of hoodwink!)

“When they carry them out of the rooms where they are kept to the fish-pools, they hood-wink them, that they be not frightned by the way. When they are come to the Rivers they take off their hoods, and having tied a leather thong round the lower part of their Necks that they may not swallow down the fish they catch, they throw them into the River. They presently dive under water, and there for a long time with wonderful swiftness pursue the fish, and when they have caught them they arise presently to the top of the water, and pressing the fish lightly with their Bills they swallow them; till each Bird hath after this manner devoured five or six fishes. Then their Keepers call them to the fist, to which they readily fly, and little by little one after another vomit up all their fish a little bruised with the nip they gave them with their Bills.”

It seems obvious to state but then again I haven’t experienced eating regurgitated, and lightly bruised, fish but they do not sound terribly edible to me. Anyone have experience with this? If you have ever been around a cormorant nesting area, such as the one at Cape Disappointment’s Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, you will appreciate the cormorants’ ichthyophagous way of life. The aroma at these places is overpowering and disturbingly fishy. But, of course, no one’s eating the digested remains of cormorant meals, at least that I am aware of, and just because the aroma of their poop is unpleasant doesn’t mean the birds deserve our enmity.

It distresses me how often people make disparaging comments in regard to animals, their morality, their diet, their intelligence, or their mode of existence. So fie to Geoffrey, John, and Will. Certainly, no animal can top our gluttony, insatiable greed, or cruelty. Why do we think we exist on a higher moral plane or level of success than animals? Certainly, many of those beasts that we have long mocked, have been on our planet as a species far longer than us, which I would call a rather successful mode of existence for our fellow inhabitants.

I am glad that the use of cormorant as a stand-in for gluttony and greed has faded from our common vernacular. I like to think this results from a combination of heightened sensitivity and sympathy for the birds but I also suspect it’s due to people’s general lack of awareness of cormorants (why exactly were they so well known back in the day?), as well as a simple change in language. Sadly, we have far more and far better known human examples of gluttony, greed, and cruelty that we can reference than having to rely on cormorants, who are none of the above.

I will end with my favorite description of cormorants. It comes from the great poet Robinson Jeffers, who would have regularly seen the birds from his home in Carmel, California.

“the cormorants

Slip their long black bodies under the water and hunt like wolves

Through the green half-light.”

In the Seattle area, we have three species of cormorant: Brandt’s, Pelagic, and Double-crested. The first two have a coastal lifestyle and the latter, more wide ranging, often inland. Double-cresteds (more common) and Pelagics are further notable for their practice of standing with wings spread, like a photophillic tan seeker. They do so, according to my pal, the splendid birder Lyanda Lynn Haupt in her Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds “to dry, probably to ready their wings for flight, and possibly for thermoregulatory purposes as well.”

Good places to cormorants are along the Ship Canal, the Locks, Alki Point, and West Point.

Upcoming talks:

January 11 - 7pm - Third Place Books - Lake Forest Park - Liz Nesbitt and I will be together chatting about our new book Spirit Whales and Sloth Tales: Fossils of Washington State. Here’s a link to register.

January 18 - 6pm - Edmonds Bookshop - Liz Nesbitt and I will be together chatting about our new book Spirit Whales and Sloth Tales: Fossils of Washington State.

Years ago, when I commuted on the (old) 520 bridge to Kirkland on the bus, I used to love looking for cormorants and other birds as I crossed the bridge. The cormorants often lined up on the buoys that ran parallel to the bridge, one per buoy, usually with their wings outstretched, all the way across the lake. It felt like a welcoming party, especially since the old bridge was so low to the water so I was almost on level with the buoys.

As a biologist working on habitat restoration, I've heard more than once some blame cast on cormorants as the species preventing recovery of species like Chinook salmon. Like other piscivores, they're just trying to get by but they happen to be eating the same things we like to catch. I sense a bit of jealousy in their older descriptions as greedy; more likely, they are just super-efficient predators and that might be frustrating to the shoreside person fishing.