In 1998, my wife and I bought our house in Seattle in part because of the three Douglas firs in the backyard, two of which were too wide for me to wrap my arms around. We have not regretted it. I have watched Bald Eagles, Cooper’s Hawks, and Barred Owls perch in them. I have been transfixed by Red-Breasted Nuthatches going up their trunks and Brown Creepers descending their trunks. I have marveled at the beauty of the spiral branches, examined their furrowed bark for spiders and other bugs, and simply sat under and enjoyed their splendor.

But I also connect to and revel in these astounding tree on a more visceral level. I have long considered myself to be a natural history writer. By that I mean that I am interested in the nature and history of a place and the plants and animals that inhabit that landscape. Few plants better illustrate my interests than the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziessi) in our backyard.

Consider their common name. First applied to the plants in 1833, in the Penny Cyclopaedia (produced by the wonderfully named Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge), the name honors Scottish botanist David Douglas, who had collected specimens along the Columbia River in 1825. He described one tree with a 48 foot circumference, noting that some “even exceed that girth.” To Douglas, the “remarkbly tall, unusually straight trees” were “one of the most striking and graceful objects in Nature.” They have also been called Douglas spruce and Oregon pine.

The common names illustrate the confused state of botanists who have struggled to figure out where to place the tree in the tree of life. The genus vacillated between Abies (true firs) and Pinus (pine trees) until 1867, when scientists gave the trees their own genus, Pseudotsuga, a lovely combination of Greek (pseudo=false) and Japanese (tsuga=hemlock). Not until 1950 did the species receive its present specific epithet, which honors Archibald Menzies, the naturalist on George Vancouver's expedition to the Pacific Northwest in 1792. He brought the first specimens to Europe. While in Puget Sound, Menzies wrote of being “regaled with a salubrious and vivifying air impregnated with the balsamic fragrance of the surrounding Pinery.”

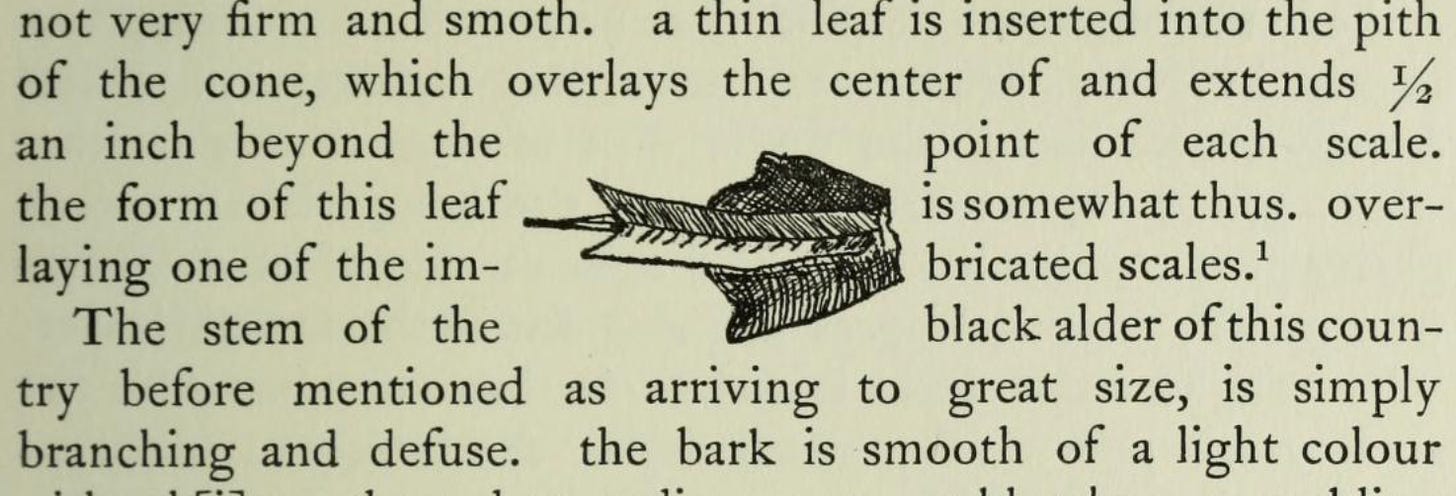

Between the time of Menzies and Douglas, another well-known visitor to the PNW noted the species. In February 1806, while camped at the mouth of the Columbia River, Meriwether Lewis wrote of what he called Fir No. 5 and included a drawing of the tree’s unique cone and its bracts, sometimes described as resembling a mouse’s tail or a forked tongue.

And, of course, long, long before Europeans arrived the Indigenous peoples of the region had names for the tree, which still persist. Ethnobotanists such as Nancy J. Turner of the University of Victoria have written of names that refer specifically to big (old) trees, young, second growth trees, and real-trees, as well as terms for preparing the boughs for a sweathouse or bedding. In Puget Sound, the Lushootseed name is čəbidac, which I have seen translated as large-tree or a reference to the bark.

Indigenous names such as these reflect cultural and ecological relationships with the tree that span generations. Non-Indigenous plant names are also about relationships but more often ones centered on who first collected a specimen or made it useful (a.k.a. of economic importance), though many common plant names do reference a physical or geographical feature. Neither reason for coining a name is better than the other; they are simply illustrative of how different communities view the world.

I have read and heard that people find it hard to remember scientific names or think that they are merely used by “experts” and have little relevance to those outside that community. And, yet, these names often provide stories and context and a way to establish stronger connections to that species. Plus, learning scientific and common names can often help one to look closer, to ask questions (about nature and history), and to not take for granted the marvels of the natural world that surround us.

Next Thursday, March 25, 6:30pm, I am honored to be interviewing my pal David Laskin about his new book, What Sammy Knew, as part of the Books in Common NW series. We’ll talk about writing, Ivan Doig, and making the switch from non-fiction to fiction. Sure to be thought-provoking and perhaps even funny at times.

I am also pleased to announce that you can purchase a copy (or more) of Homewaters through me. The price of $32 includes shipping and an autograph. They won’t be shipped till after April 24 (publication date), but dang wouldn’t it be great to have bragging rights that you’ll soon own one, and one that’s signed, to boot?

By the way, you can follow me on Twitter @geologywriter

I read that there was a real rivalry between the two Scotsmen Douglas and Menzies and that the bracht in the cone is Douglas giving the finger to Menzies!