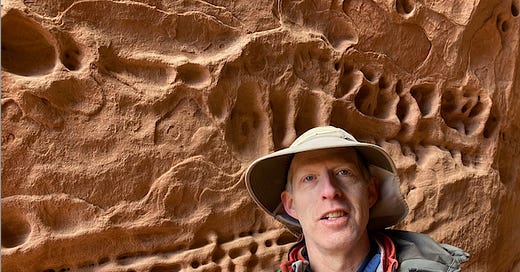

Earlier this month, I had the pleasure of returning to Moab, Utah, and the rock desert that helped foster my love affair with the geologic world. (In case you’ve ever wondered, the “wingate” in my email address comes from one of my favorite rock units—the Wingate Sandstone, which makes up the cliffs of Canyonlands NP.) While there, I reacquainted myself with a desert phenomenon that has long fascinated me: the holey, honeycomb-like features found in many sandstone areas.

I am not alone in this interest. Many scientists, including my man Charles Darwin, have long noticed these holes, calling them tafoni (from the Italian tafonare, to perforate; or possibly the Sicilian taffoni, for windows), nests, desert cavities, and alveoli (from the Latin alveolus, or beehive). One of the lesser known researchers was Petros Saxifraga, who devoted his life to seeking out what he called “those durned wee niches.”

These scientists of the past have determined that the hole-excavating culprit is one of a family of birds (Tafonidadae), commonly called rockpeckers. They occur world wide but, as the name implies, tend to be found in areas of resplendent geology, such as southeast Utah. What unites the group is their curious habit of eating horsetails, or Equisetum, plants rich in the mineral silica. Naturalists have long observed but, until recently, little understood this food preference. The breakthrough came with the development of scanning electron microscopes. Magnification at the molecular level showed that the birds concentrate the silica, a mineral much harder than the calcite that makes up their bones, in their bills, in essence turning the birds into “winged Michelangelos whose medium is rock and whose artistry is the negative space of the hole,” wrote Saxifraga.

Over the decades ornithologists and geologists have slowly begun to tease out aspects of the life history of rockpeckers. As with many details of these intriguing birds though there are more questions than answers. Some species appear to nest in the holes, some use them for storage, and some seem to simply fancy excavation as the highest form of bird life. As better techniques develop, ornithologists expect to crack open the nut of these birds’ remarkable existence.

One promising line of research centers on advanced DNA analysis, which has led some to propose a radical paradigm shift—rockpeckers are not related to woodpeckers. Instead, they may be aligned with the rock wren (Salpinctes obsoletus), birds that also have lives circumscribed by rock. In their labyrinthine world of crevices, nooks, and recesses, rock wrens build nests with stone driveways, which can contain hundreds of pebbles. Early ornithologists hypothesized that this behavior might help the rock wrens recognize their nest cavity from the multitude of holes found in cliff faces or that the walkway kept “the young from falling into crevices or getting their feet caught in the same.” Other hypotheses have focused on early predator warning and keeping nests dry but, as with rockpeckers, the debate rages on about the design proclivities of these avian masons of the desert.

Further confounding scientific expectations, rockpeckers are not alone in their ability to drill out rocks. In what scientists call parallel evolution, piddock clams (more than a dozen species, found world wide) have been boring rocks since the Middle Jurassic. Several species occur in Washington. All use their rough shells to auger out a cavity, which, similar to certain species of rockpeckers, becomes home for the clam. Just to be clear, it is only the exceptionally rare scientist who believes that rockpeckers and piddocks are closely related but as “we all know Rome wasn’t built in a day and they used tons of rocks, too,” wrote Saxifrage.

Because of these profound discoveries, rockpeckers are often cited as one of the more important fields of modern research. Now that I am home in Seattle I will, of course, stay abreast of what develops, particularly for April 1, aka April Fool’s Day.

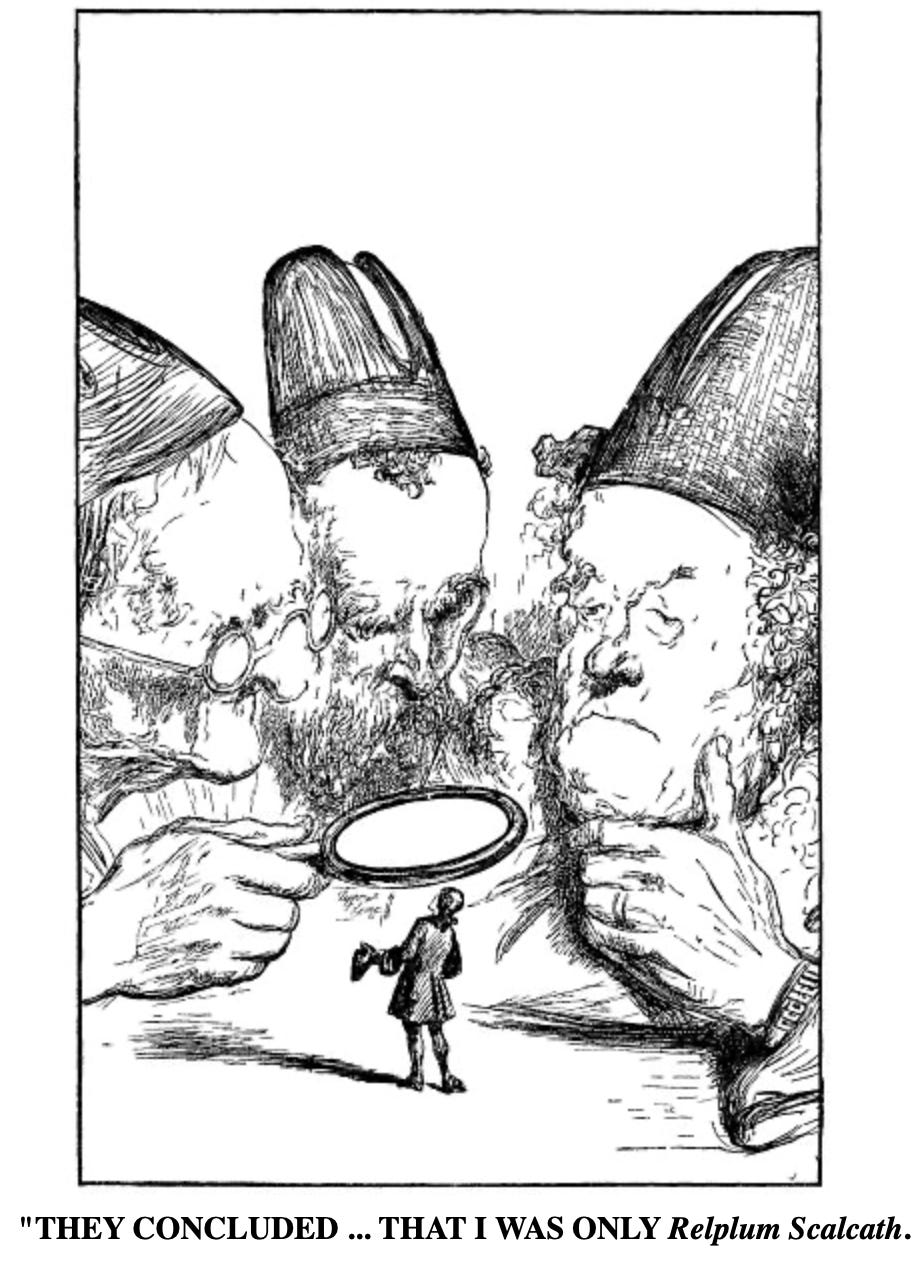

Word of the Week - Lusus naturae - Latin for “freak of nature.” One of the earliest writers to use the phrase was Jonathan Swift in Gulliver’s Travels. During Gulliver’s time in Brobdingnang, three philosophers examine him and, unable to determine who or what Gulliver, is basically pass the buck and offer a simple, yet unrevealing, description.

“After much debate, they concluded unanimously, that I was only relplum scalcath, which is interpreted literally lusus naturæ; … whereby the followers of Aristotle endeavoured in vain to disguise their ignorance, have invented this wonderful solution of all difficulties…”

'petros saxifaga' is the don quixote of geology. and those equisetum eating silica bills! 💀👏💀👏💀

As I was reading your third graph, I truly thought you'd lost it. Lusus indeed. A good laugh, one day early.