Apparently not all pinnipeds read guide books. At least that’s my conclusion after seeing a harbor seal on Saturday on my weekly ride with my pal Scott on the Centennial Trail. The spotted, gray seal was almost 18 miles away from the nearest harbor, up the Stillaguamish River. As we usually do, we stopped on the old railroad bridge over the Stilly, near Arlington. Below, the water was clear and as low as we have seen it: 560 CFS compared to the maximum we have seen of more than 60,000 CFS. The harbor seal was at the surface in the middle of the river. I could see her spots as she bobbed and swam along for a few seconds before diving and swimming toward the shore.

When I reached out to Pete Verhey, a fish biologist for the Department of Fish and Wildlife, he told me that harbor seals that head up river are a “good sign that Chinook [salmon] are pressing into the rivers. Chinooks or pinks.” He also noted that the estuary, aka the harbor, of the Stilly is home for a harbor seal colony nearly year round. It consists of “mostly females [who] likely rear their pups there in relative safety.”

Seeing the seal was yet another reason I enjoy riding along the trail weekly. I have noted in a previous newsletter that the trail is nothing special—along roads, through fields, and mostly flat. Instead, it is the cumulative sightings of wildlife and weather over more than seven years of riding that have given me a deep appreciation for the area, its diversity and its dynamic.

Harbor seals are arguably one of the most beloved and endearing animals in Puget Sound. Go to the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, ride a ferry, or walk along the waterfront, and you’ll probably hear someone cooing and oohing over a harbor seal. With their large eyes, canine-esque appearance, gregariousness, and what seems to be a curiosity in people, harbor seals appeal to us on many levels.

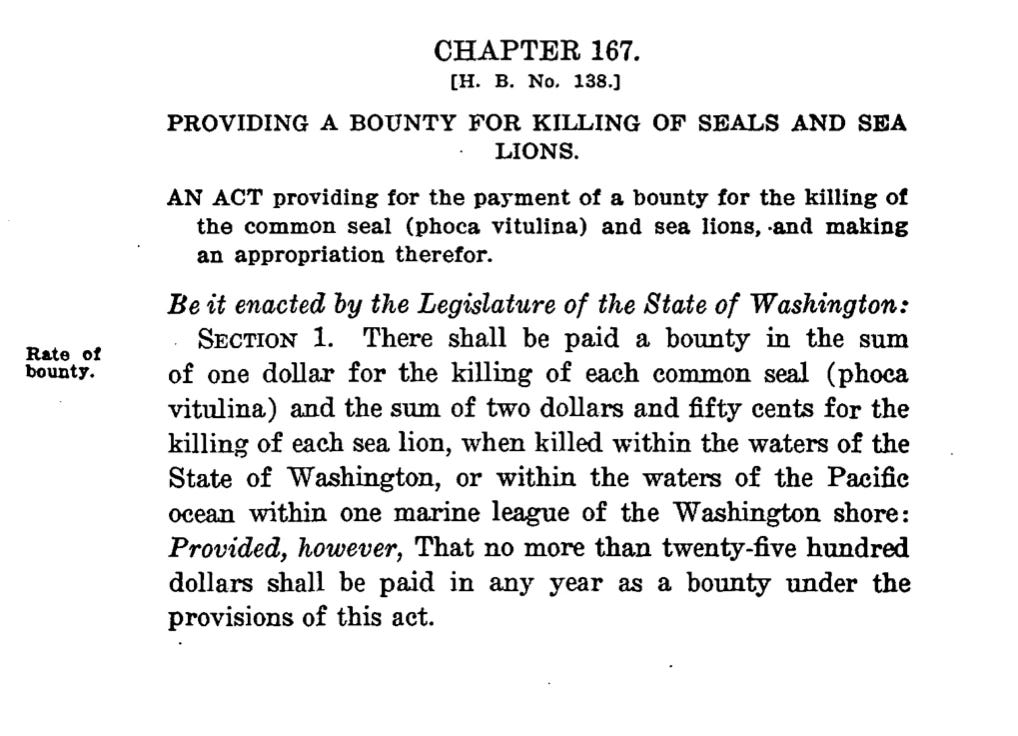

At least they do now. Such was not always the case for harbor seals and sea lions. Historically, Puget Sound’s commercial fishers scapegoated the big piscivores, claiming that they ate too many salmon. This led to the Washington State legislature passing legislation offering a bounty in 1903: $1 for a seal and $2.50 for a sea lion. In 1947, legislators raised the bounties to between $3 and $10 for both seals and sea lions.

Three years before the bounty rate increase, biologists Victor Scheffer and John Slipp wrote that between 1922 and 1926, 3,200 harbor seals had been bountied. They also wrote that another 40 percent should added to the total because of seals killed but not recovered. Describing the “constant persecution” of seals by sportsmen and others, they wrote: “Blame for the decline in a local fishery is often directed at the harbor seal, whereas it rightfully belongs to selfish or thoughtless practices of man, such as overfishing, the damming of streams, pollution by industrial wastes, and so on.” Sixteen years previously, in 1928, Victor’s dad Theophilus, expressed the same sentiments. Sadly, neither of their wise words took.

Pinnipeds continued to be hunted toward extirpation until 1972 and the signing of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), which prohibited the taking of all marine mammals in US waters. Since then, Washington’s seal population has ballooned from around 5,000 to almost 44,000: Hood Canal = 2,832; South Puget Sound = 2,529; Northern Inland = 15,796; Coast = 22,451.

We humans may like to see an increase in harbor seals but our joy pales to the benefit provided to Bigg’s killer whales. These are the mammal-eating group of orca that inhabit the Salish Sea, whose numbers have steadily climbed in the past few decades. Their population increase corresponds well with the rise of the harbor seals.

Speaking of orcas, one infamous individual swam into Lake Union in February 1938. Nicknamed Nosey Joe, the orca (historically known as blackfish) initially swam into the larger locks at Ballard, moved in and out of it for about an hour, and then entered fresh water, making it all the way to Lake Union. In pursuit was Edward Sierer, a Seattleite who hoped to harpoon the orca. Fortunately, Nosey Joe returned to the locks and headed back out into the relative safety of Puget Sound before the Queeqeeg of Seattle could kill the unsuspecting orca.

Scott and I continued to look for the harbor heal after she swam toward shore but she didn’t reappear. We also looked again on our return part of the ride. Again, no luck. But that’s okay. Simply knowing that harbor seals venture so far inland, knowledge gained only after seven years of riding, has now opened us to the possibility of seeing them again. That’s half the fun of paying attention; I generally look for what or who I hope to be there, as well as remaining open to unexpected discoveries. Either way, I have fun.

July 22 - 6pm - Who’s Watching You - Birds Connect Seattle - Still a few spaces open for my walk with BCS looking at human and terra cotta carved people and animals (including a few birds) on downtown buildings. Registration.

Share this post