The other day I went for a run through the Union Bay Natural Area, a place I have visited for decades. As I always do, I stopped at what I call my dad’s bench on the south side, which has a plaque in honor of my father. He and my mom spent many hours there birding, so it’s a special place for me to go and still is a wonderful place to see birds, more than 200 species of which have been sighted over the years. Here’s a link to one of my favorite blogs about Union Bay.

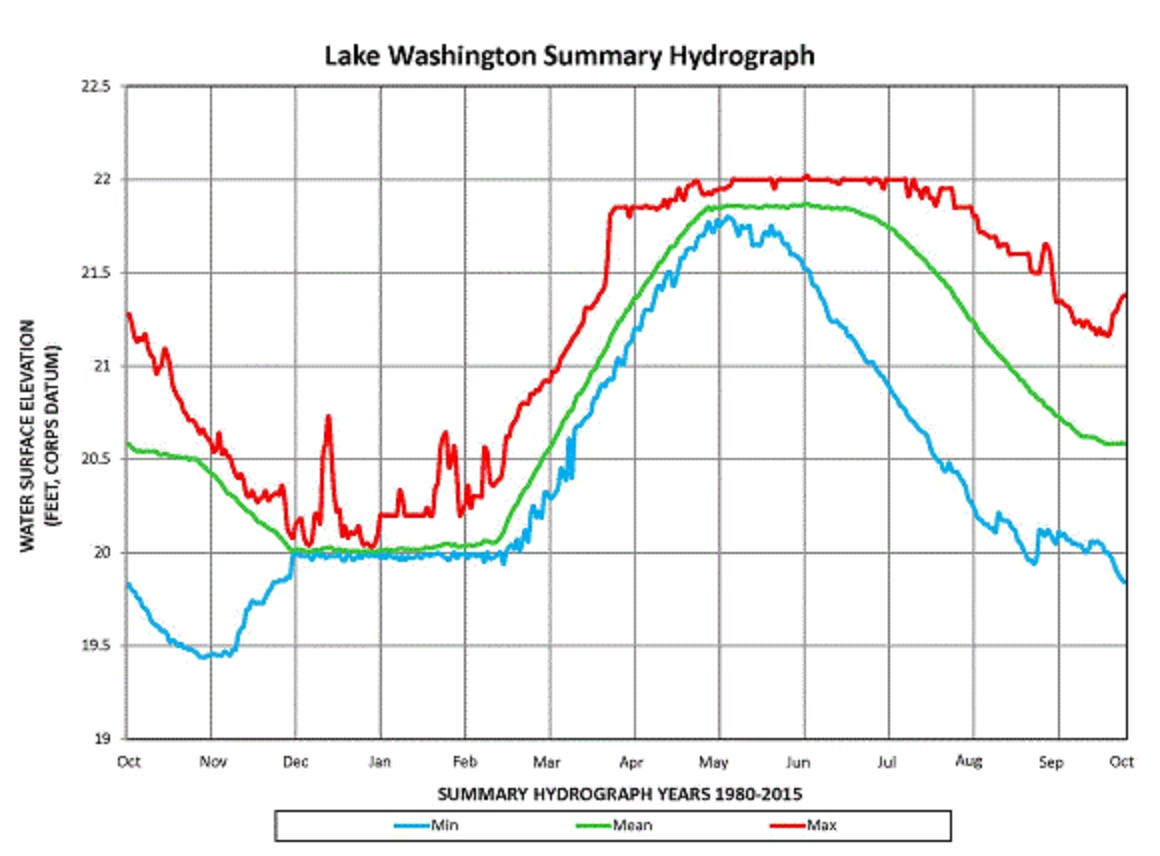

In addition to watching for birds, I also pay attention to the water level of Lake Washington, which fluctuates throughout the year. The other day it was high with water pushing up to the edges of the trail in a few places. (Recent maintenance made a huge improvement to the trail by raising it up; previously, parts of the trail were underwater when the lake level was high.) This water level is neither normal nor natural.

Prior to 1916 and completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, Lake Washington naturally see-sawed as much as nine feet (and perhaps more) during the year. The variation was so large that historically what is now Seward Park would periodically become an island due to water covering the isthmus that connects the peninsula to the mainland. (In 1912, when the Olmsted Brothers were planning Seattle park’s system, some locals agitated for a canal through the isthmus so that tour boats could pass through. They stated that the steamers would be a boon to “poor people [who] had no means of getting to Bailey Peninsula…without walking a great way,” noted Olmsted employee James Dawson in a report to the parks on April 5, 1912.)

In contrast to the present situation, the lake’s historic high level was in late winter and early spring—due to rain and spring runoff from the Cascades. At present, the Army Corps of Engineers restricts the water level to between 20 and 22 feet above sea level. “The minimum elevation is maintained during the winter months to allow for annual maintenance on docks, walls, etc., by businesses and lakeside residents, minimize wave and erosion damage during winter storms and provide storage space for high inflow,” according to the Corps. If the lake dropped too low the cables holding the floating bridges in place would become slack and lose their integrity. Plus, too much change would not be good for houseboats and moorings on the lake.

This unnatural water level regime may benefit property and people but it is not good ecologically. Retired University of Washington ecologist Si Simenstad describes this change as “upside down seasonal hydrology.” For plants adapted to a winter high, a summer high can be catastrophic. Emergent plants typically set seed in the autumn and germinate that year or the following spring. During the modern hydrologic regime, the plants don’t have enough time out of the water in the summer, when they need to get established and grow. Add to this ecological challenge the secondary effect that these plants adapted to relatively large fluctuations must now try and grow in an environment that is essentially static and you have a recipe for a less healthy ecosystem.

Walking around Union Bay, I am always amazed by the diversity of life there. (On my run, I also saw a turtle and her trail of foot and underside-of-her-shell tracks.) Sixty years ago this area was the location of a dump where trucks belched up between 40 and 66 percent of Seattle’s trash every day. Over the past several decades, however, the area has been restored. (Not exactly to what was there historically, but to a more natural state; this area of land before the lake level dropped with the Ship Canal was a bay of water north to what is now NE 45th Street.) The lake levels I saw were unnatural but Union Bay Natural Area is still inspiring, showing we can try and right some of the mistakes of the past and that restoration can work to create a functioning and lovely community of lives, human and more than human.

Thanks for the reminder of the backwards nature of seasonal high water in Lake Washington. The lake has a kind of sterile looking shoreline character in my experience. The reverse high water season and its relation to plant establishment might be why.

As I type this, I am sitting on your father’s memorial bench. I did not realize till I read your entry the connection. This is a favorite place of mine to sit as it is cool in the summer and a bit secluded. A common yellowthroat is hopping from branch to branch as I enjoy the shade. UBNA is my place to go when I need to be re-centered; immersing oneself in one of the many tiny ecosystems found here has that effect. Thank you for the history and insight into the ongoing challenges of this piece of urban wild-ness.