Few events exemplify Puget Sound’s many circles of life as abundantly as a herring spawn. The excitement begins when male herring start pumping out milt that can be so prodigious it turns the water a creamy turquoise. In response, females release between 10,000 to 45,000 fertilized eggs per fish, which settle and stick on seagrass, where fertilization occurs. During massive spawning events millions of fish are involved, and then, several weeks later, the fish migrate back to their normal feeding grounds, either elsewhere in the Sound or out in the open ocean.

With their astounding bounty, such events have been magnets of life for thousands of years. For the Indigenous people of the Sound and the Salish Sea, the great schools of herring were essential, not simply because of the vast numbers of fish but also because of the timing when the herring returned. Adult fish began to arrive in early winter and late spring and provided valuable meat and oil, at a time when other foods might not be available. In addition, the birds and mammals attracted to the herring could have provided further resources. Such hungry visitors would have included animals such as wolves, humpback whales, bears, seals, bald eagles, porpoises, and deer.

Animals seek out these teeming schools because herring “are really good at eating tiny, crunchy things and converting them into delicious fatty meals,” as one biologist told me. Herring are first level consumers, vacuuming up detritus and phytoplankton, or microalgae, and in turn, getting eaten by secondary consumers. In this role between the lowest and highest levels of the food chain, herring connect everything in Puget Sound, says Ole Shelton, a NOAA ecologist. “They connect the open ocean to the coast. They link predator and prey. They transmit nutrients between ecosystems. They are very much the hub in the wheel of the Sound.”

While working on Homewaters, I was fortunate to witness two spawning events. The first was at Alki Point, where I joined my pal Lyanda Lynn Haupt to watch rafts of surf scoters with their lovely black bodies, white head patches, and colorful bills. They would periodically disappear beneath the surface, descending in search of eggs, and then pop up like corks and rest on the surface eating. The highlight was seeing a flying fish, or at least an adult herring passing over us in the talons of an osprey. But then the osprey returned back over the water, followed by a bald eagle pursuing the sea hawk and his hoped-for-meal. The osprey soon dropped the fish and the eagle abandoned her pursuit but seemed to decide at the last minute a dive into the water for the herring wasn’t merited. Both then went their own ways.

My second spawning event occurred on Hood Canal at Right Smart Cove, about six miles south and two coves west from a location known to the Skokomish people of Hood Canal as “landing for herring,” a reference to its importance as a spawning ground. On the water were several hundred scaups, surf scoters, buffleheads, American wigeons, and goldeneyes. Another raft a quarter mile south was less diverse, almost all surf scoters, but larger, with what looked to be well north of a thousand birds.

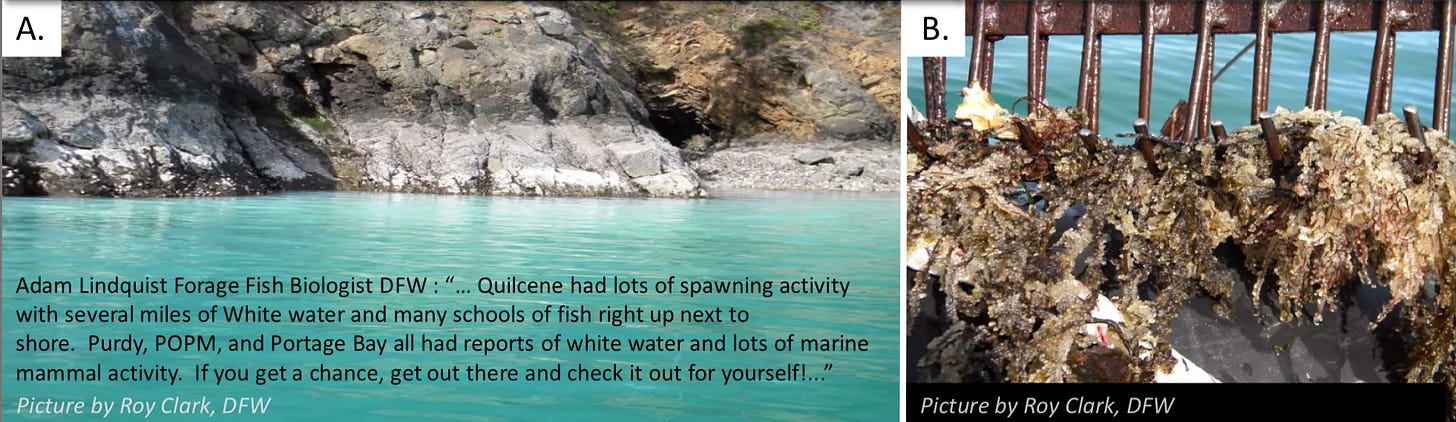

On the beach, my wife and I found eggs that had washed ashore and formed small islands, four to five inches deep and up to fifteen feet long and several feet wide. In the water that swirled in a small eddy, the eggs were so thick that the water had the consistency and color of watery Malt-O Meal, though I assume the eggs taste better than the cereal to those hoards who descend to eat the wee nuggets of energy. Digging my hands into the piles, I scooped up a football sized mass and could see many with tiny eyes. So cute but sadly also destined to die, as few eggs that washed ashore could survive being out of water.

Luckily for those in Puget Sound, we are in the middle of the spawning season. It typically begins in January, in Wollochet Bay, Quartermaster Harbor, and Port Orchard, and continues through the end of June, at Cherry Point. In the past few weeks, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has reported spawning activity in Hood Canal, which over the past few years has experienced big events that attracted stunning numbers of birds such as I saw. Go check it out.

N.B. As with many scientific names, that of Pacific herring, Clupea pallasii, has an international pedigree. The specimen that inspired the scientific name was collected in Kamchatka in the 1730s or 1740s; acquired by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas later in the century; bequeathed upon his death to his Swedish friend Karl Rudolphi; then given to the German director of the Berlin Zoological Museum Martin H.C. Lichenstein who provided the fish to French ichthyologist Achille Valenciennes, who finally published the first formal description in 1847.

Erratum: In my previous newsletter, I made a directional error. In contrast to what I wrote, Brown Creepers typical spiral UP a tree and not down. Plus, I should have written menziesii and not menziessi. Oh well. That’s why I really like copy-editors.

Big news. A beautiful copy of Homewaters arrived in the mail on Saturday! Such a pleasure to hold it in my hands. This is the longest gestation period for any book of mine. I began interviewing people for it in October 2016. I like to think it is my best book yet. The book launch will be May 3. You can buy copies through me. Heck, I’ll even sign or inscribe them…for free.