For the past few years, I have been working to change the way I speak and write. In particular, I have been focused on the use of pronouns in connection with animals. My goal has been to try and stop using it. Instead, I am trying to use he or she to reference an animal. Despite my attempts and earnest interest to change, I have found this to be challenging, to reimagine and reconsider the way I have long spoken and written.

I am certainly not the first to reflect on this issue. My thinking has been influenced by the writers Robin Wall Kimmerer and Lyanda Lynn Haupt. Both address the idea that the use of it objectifies animals, as if they were not sentient, living beings who feel pain and loss. Certainly the world saw that this is not the case, sadly, with Tahlequah, the orca mother who carried her dead calf for 17 days covering more than 1,000 miles. Imagine that sentence with its instead of her.

The use of it is standard practice when someone refers to an animal. No matter the species, whether swimming, walking, or flying, invertebrate or vertebrate, predator or prey, liked or loved, there is no discrimination, it is the word of choice when the speaker or author moves away from the specific (such as bald eagle) or generic (such as bird). This even occurs when the use of it clearly makes no sense. For example, in a November 15, 2021, story about deer in the New Yorker, Brooke Jarvis wrote: “Before long, the buck opened its eyes, twitched its ears, and raised its head. Then it climbed to its feet and walked into the night....”

My guess is that nearly everyone who reads Jarvis’ article knows that bucks are male deer, a use that dates back more than 1,200 years. Wouldn’t the story and the connection the author was trying to make to this specific animal, be stronger with he and his instead of it (which the OED defines as “with reference to an inanimate thing”)? When I reached out to Brooke, she told me that she tried to use he but that using it was a policy of the New Yorker. The magazine is hip enough to use swear words and they as a pronoun. Seems like they could easily adapt a new policy for animals.

The New Yorker is certainly not the lone example. I was recently reading a book where the author used birds and birding as metaphors for her life. She was clearly enchanted with birds and took the time to be a diligent observer and learn about them. Throughout the book though she consistently used it, even with sexually dimorphic birds. I have no idea if the use of it was the author’s or editorial policy but the its made her prose less dynamic and more distant from the birds, especially when the author knew the sex of the animal.

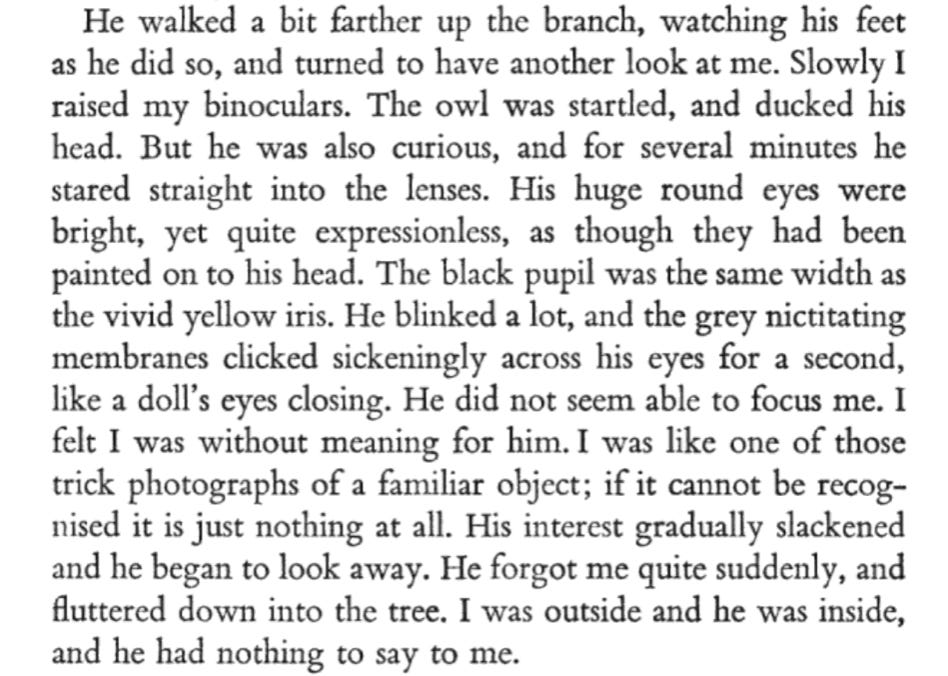

In contrast, here’s a description from my favorite book about natural history. In The Peregrine J.A. Baker clearly shows how he/she helps reveal the animal’s complex and dynamic world. I don’t know of any other writer who brings birds to life in such vivid and vibrant language.

I certainly understand that it is not always possible to know the animal’s sex but in those situations it is often possible to still avoid it. One could use “the fox,” “the hawk,” “the fish,” or use the plural so that they is appropriate. Lyanda told me that when she refers to an animal without obvious sexual dimorphism and uses he, no one blinks, but if she uses she, everyone wants to know how she, Lyanda, knows that the bird or other animal is female. As Lyanda said: “In moving beyond it we also need to move beyond the male pronoun as a catchall for all beings.”

When I wrote Homewaters (which is when I started thinking about this issue), if I didn’t know whether an animal was male or female, I would ask someone more knowledgable if there were any clues that would point to the sex and if not, could I choose. I know that I was not always correct but I still wanted to try and honor the animal as a living being and felt it was okay to use he or she. And, I still struggle with he/she for invertebrates but when I do know I have been quite pleased to write about a male butterfly or female oyster.

As many others have written, the use of it creates a rift making nature different from us, humans, the only species who merits a pronoun other than it. (And, of course, our use of pronouns in reference to people is changing, too. ) All those others out there, those its, must be different, and by implication, lesser than us, which is often the first step to discrimination, and in the case of nature, degradation. I hope that pausing to consider that an animal is far more than an it will lead us on a path to deeper, more nuanced, and respectful relationships with the natural world.

One of the challenges to this point of view is the limitations of English. We don’t have a pronoun that would truly suffice in recognizing the sentience and animacy of animals, yet another challenge to strengthening our relationships to the natural world. And, he and she aren’t truly the best option. They are simply one way to forward the conversation.

I fully recognize that I am writing with the zealotry of a recent convert and am sure that I have annoyed my friends “correcting” their use of it. But in doing so, I know that we have had thoughtful discussions about language and our relationships to the natural world. Words are powerful messengers of our feelings and the more we consider carefully what we say and write the more we will recognize that all species, human and more-than-human, have complex lives filled with beauty, mystery, and majesty. And, perhaps, in doing so, we will make the world a better and safer place for all around us.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this issue. Thanks.

March 12 - IslandWood - Bainbridge Island - 3pm - I will be talking about Homewaters, followed by a Happy Hour. Sure to be fun.

March 15 - History Cafe - MOHAI - 6:30pm - I will be talking about Homewaters. Live and virtual.

A timely post David, as more humans push for a gender-neutral pronoun. In fact, I pay a dollar every time I slip up and call my friend "she" instead of "they". (But in fairness, that young friend has paid me a dollar when they say anything vaguely ageist.) I will add that "it" feels like a dismissive slap when you are talking about a living creature.

This change recognizing animals are not things can go beyond pronouns. Officially, humans "lie" down for a nap. But you "lay" a book down on the table. When I was teaching, I always used the verb lie for animals. Students would challenge that use. I'd always ask if they had a pet, or had ever loved an animal. Then I'd ask did that animal have more in common with their family members, or more in common with a log in the fireplace? They always agreed with the use of "lie".