A small gang lives in my Seattle neighborhood. Like most gangs, the members look alike; slate, gray, and green dominate the color scheme. They like to hang out by the corner telephone pole. Sometimes they burst into one of my neighbor's yards and harass them. They don't hurt anyone, but they can be troublesome. I am not bothered by this gang. I am in the minority; most people dislike these pigeons.

They say that pigeons are dirty birds, that they mob backyard bird feeders and steal the food from "more worthy" birds. They say the pigeons don't belong in our quiet neighborhood. They want to rid the local park of what have been called "rats with wings."

Rumor has it that pigeons, or rock doves, reached the Seattle area within days of the first pioneer's arrival. This is rather hard to prove but pigeons are certainly omnipresent in the Emerald City. (Pigeon Point in West Seattle may by named for our local pigeon, the band-tailed pigeon (Patagioenas faciata).) Seattle is not unique in this avian invasion. Native to Europe, Africa, and Asia, pigeons nest, eat, and procreate on five continents. The earliest North American records are from 1606 in Port Royal, Nova Scotia.

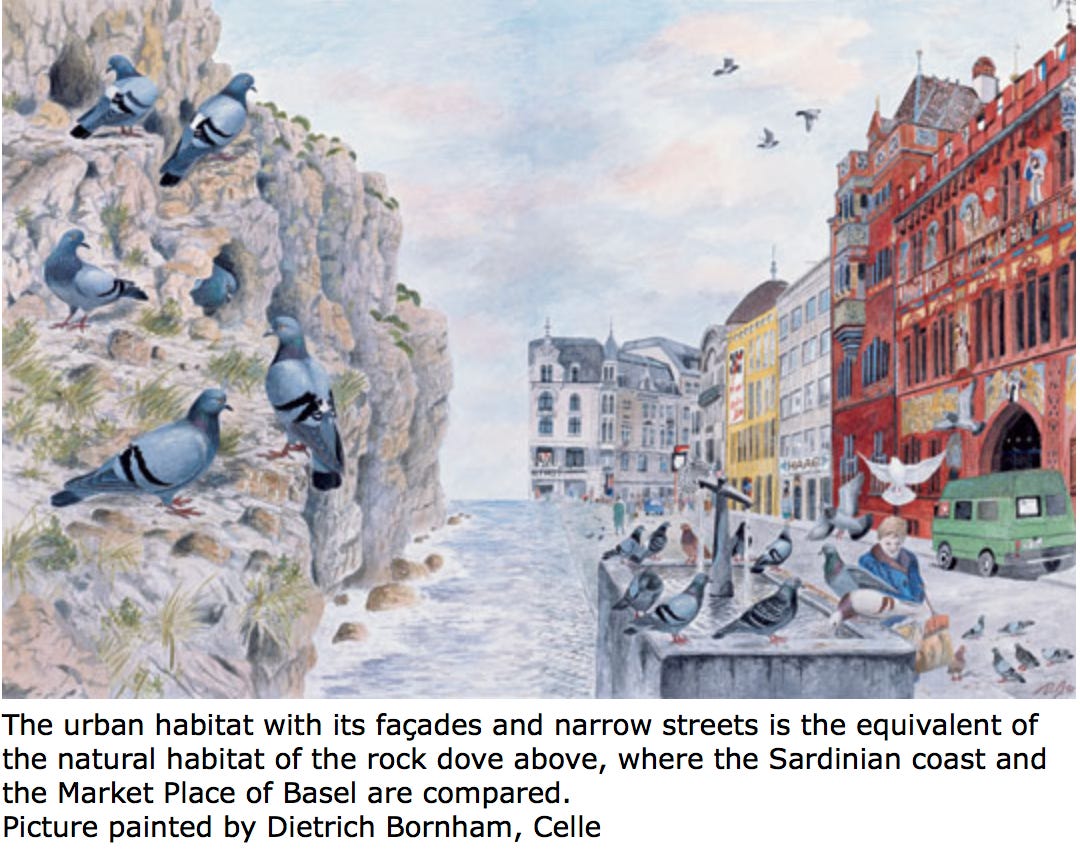

We, of course, can blame no one but ourselves. Humans have customized cities for pigeons. Our propensity for dropping edible morsels provides plenty of food for the birds. We build deep chasms of buildings that simulate pigeons’ native habitat of canyons with numerous clefts for housing (hence rock dove). We even construct buildings that offer prime nesting sites: small, well-protected ledges. (Some people believe that pigeons must emerge fully grown because they have never seen a young pigeon. This is not true; the young just have good parents, who feed and watch over their progeny, known as a squab, until they are large enough to fledge.)

Despite our dislike for the bird, they have many admirable qualities. In addition to being good providers, urban pigeons are models of fidelity. Unlike some urban dwellers, pairing for life is the norm in pigeons. This may occur because the birds are sedentary, constantly together, and able to reproduce year-round.

What we consider to be an ungainly animal can fly faster than most big league pitchers can throw a baseball. Homing pigeons, trained to take advantage of the bird's speed and navigational skills, have been used for over 2,000 years. They carried news of Caesar's conquest of Gaul back to Rome. After Napolean's defeat at Waterloo, a pigeon carrying the news beat a horse and rider back to London by four days.

Pigeons even learn from each other. In one study, four birds were trained to obtain food by poking a hole into a paperboard feed box. After returning the birds to their old haunts, the researchers tracked the spread of the new skill. Within a month, 24 other birds had mastered the technique.

Another attribute we may fail to credit is the bird's vacuuming ability. When we see pigeons eating those discarded hot-dogs, sandwiches, or cookies, we should realize that the birds help keep the urban world a cleaner place and prevent the food from ending up in the mouths of true rats. Sure pigeons produce prodigious quantities of their own waste, but at least deposition is generally concentrated around their nesting spots.

We can also credit pigeons for playing a key role in one of the most important ideas ever proposed: natural selection.

In the first chapter of On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin wrote: "Believing that it is always best to study some special group, I have, after deliberation, taken up domestic pigeons." He raised them, collected their skins to study, and joined two pigeon clubs in London. His studying was not for idle curiosity but served a purpose; Darwin thought that human manipulation of pigeons could be looked at as analogous to natural selection. Breeders chose certain attributes in a pigeon that they liked and bred the birds to try and produce an animal that always showed this feature. Over time this type of selection led to a new breed. Pigeons, therefore, exemplified "natural selection," even if humans controlled it.

An argument has been made for other urban species, like starlings and dandelions, that we often denigrate those most like us. Like us, pigeons are adaptable, reproductively successful, and cosmopolitan. Perhaps we should grant them more respect, after all Charles Darwin appreciated them and he knew a bit more about the natural world than the average person.

This newsletter is free. If you want to subscribe, here’s a handy button. By the way, I have copies of several of my books for sale, too.

Readers Respond: A slight deviation. I had to mention this because it’s a line that every author hopes to read. It’s from biologist Orlay Johnson, writing about Homewaters in the newsletter of the Washington-BC Chapter of the American Fisheries Society. “I can begin by saying this is one of the best books (perhaps the best) I have ever read.” Thanks, Orlay.

Wishing everyone a safe and healthy Thanksgiving or however you choose to celebrate.

That same nickname "flying rat" has been associated with Crows. Both Crows and Pigeons have a place in the world that we modern humans like to forget. We think we live in a perfect world with no debris or even other species that do not meet our standards. HA! Those are the birds a lot of us love the most. The underdogs(birds)!!

Plus another side if the life of a Rock Dove - Often I will be hiking in the woods on the outer reach of our "progress" and hear this low cooing sound. Then a rustle. To my delight there is the Rock Dove hanging out in the wild.

A treat for all of us "Flying Rat" lovers.