For thousands of years, Coast Salish people kept woolly dogs for their splendid coats, the wool of which could be woven into blankets and other items. Unfortunately, the dogs went extinct in the late 1800s and only one pelt, that of a dog named Mutton, exists. Today, an international team has released their cultural and genetic study of Mutton via a paper published in Science. (“The History of Coast Salish ‘Woolly Dogs’ Revealed by Ancient Genomics and Indigenous Knowledge” was embargoed until 2pm EST, which is why I had to wait to send out my newsletter.)

Research takes place in many locations, from the field to the lab and even in seldom-visited drawers of museums. Such is the case with Mutton, the Coast Salish woolly dog companion of naturalist and ethnographer George Gibbs, who obtained him in 1858 or 1859 somewhere around the Salish Sea. (No information exists as to the exact location but it was probably along the Fraser River or perhaps around Puget Sound.) Like many dogs, Mutton was an opportunist; in 1859, he ate the head off a mountain goat specimen that had been given to Gibbs by another naturalist, Dr. Caleb Kennerly. In response, “Mutton was sheared a short time ago, & as soon as his hair grows out we will make a specimen of him,” wrote Kennerly, when he sent Mutton’s pelt to the Smithsonian’s Spencer Baird on August 19, 1859.

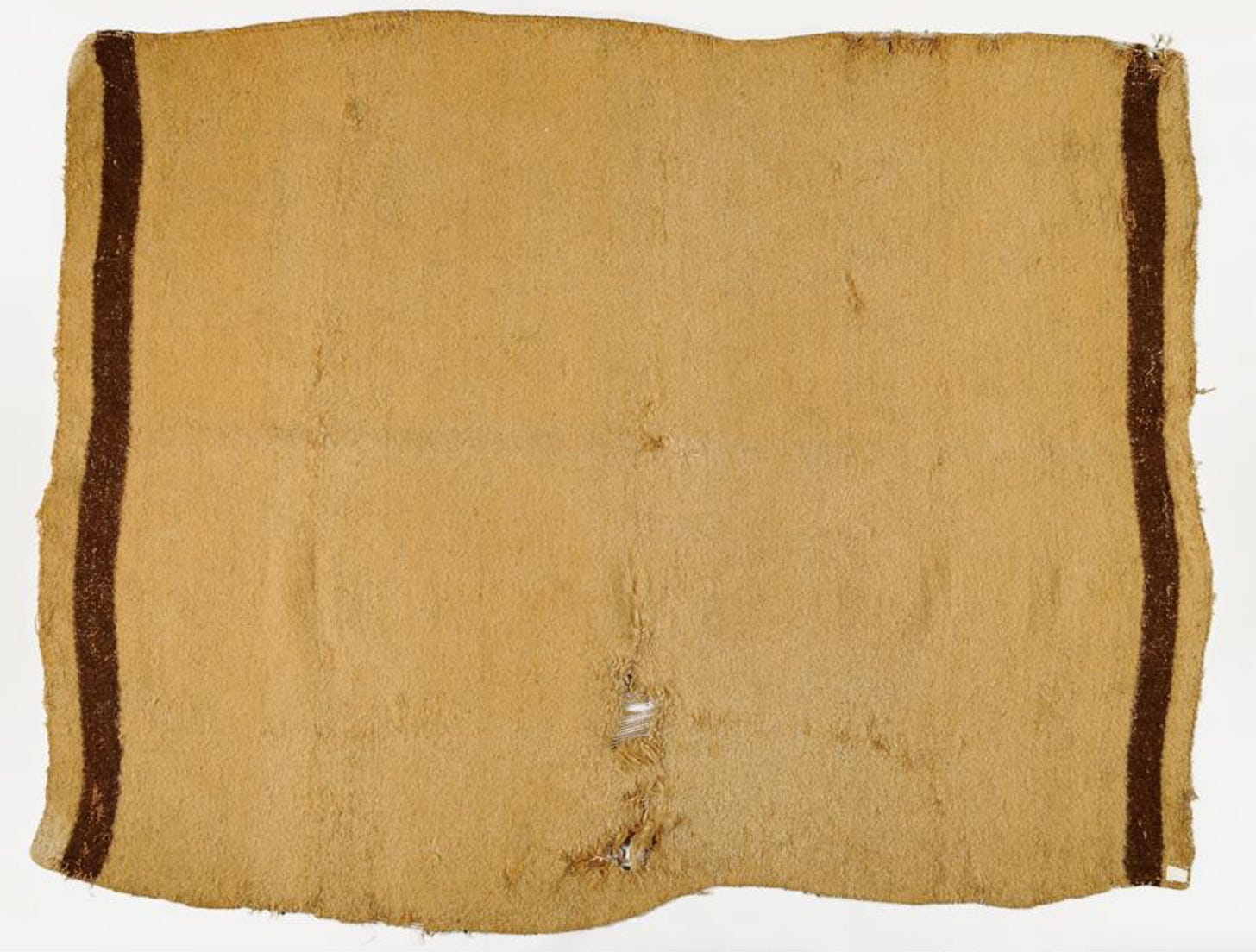

Mutton’s mortal remains sat—overlooked and mostly forgotten—in a drawer at the Smithsonian until researchers Candace Wellman and Russel Barsh separately tracked him down in 2002. Then in 2021, Audrey Lin, an evolutionary molecular biologist at the Smithsonian learned about Mutton. “I had heard from some other people that he was a bit scraggly, but I thought he was gorgeous.” She also learned that no one had ever made an extensive study of the pelt.

Teaming up with a diverse group of researchers, including First Nations and Tribal members whose ancestors had long kept woolly dogs, Lin began a genetic and cultural study of Mutton. Genetically similar to pre-contact dogs from Newfoundland and British Columbia, woolly dogs diverged from other breeds as long as 4,776 years ago, about the time they appear in the archeological record. Researchers also found 28 genes associated with hair growth and follicle regeneration. The various mutations are linked to “curly hair phenotypes in other dogs, rats, and mice [and] woolly hair and hereditary hair loss in humans.” (Apparently I share that, or a related, gene for hair loss; thanks mom and dad!) The data further indicated genes connected to woolly mammoths, though none of these charismatic megafauna lived anywhere near woolly dogs; I simply added this because I like making connections between seemingly unrelated thing, or species.

From a visual point of view, the most intriguing part of the study is what Mutton looked like. The illustration below by Karen Carr is based on Mutton’s pelt, data from an excavated woolly dog skull, the dimensions of existing, living dogs, and descriptions of woolly dogs from the literature. It is the first time that a reconstruction has been based on actual remains. (Another newsletter of mine about woolly dogs contains a couple of additional images.)

I was further fascinated by the analysis that showed that Mutton’s diet reflected his life with George Gibbs. Compared to another dog (though not a woolly dog) collected by Kennerly, Mutton had a more, terrestrial-food based diet, which may have included the entrails of bird and mammal specimens that Gibbs encountered and collected, as well as animals such as pigs and cows. Danielle Morsette, Master weaver, Suquamish and Shxwhá:y Stó꞉lō, however, noted that food given to woolly dogs would have been different with Native people. “My teacher, Virginia Adams. She had mentioned that they were only fed like salmon and just really like such a good diet to keep their coats nice and fluffy.”

That concern and care for woolly dogs shows up in the genetic data. Nearly 85% of Mutton’s ancestry can be linked to pre-contact dogs, indicating that Indigenous people retained the dogs’ unique genetic makeup, despite the incursion of settlers and their dogs. “The study opens your eyes to what it must have taken to manage the breed, not just in terms of keeping the breed separate from the hunting or village dogs but the husbandry, the feeding, the veterinary skills, the management of the breeding to develop the wool characteristics, and the fact that these husbandry skills had to continue through generation after generation after generation. It isn’t just knowledge, it becomes part of the culture,” says textile expert and study co-author Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa.

For me, one central aspect of the study is how it illustrates the importance of not relying solely on science. Woolly dogs clearly cannot be separated from the people whose lives intertwined with them. As study co-author Michael Pavel, a Skokomish Elder, has said: “Non-natives, particularly Indian agents…didn’t want the dog producing wool when those would maintain traditional practices that would prevent their ‘civilization.” Addressing how racist policies, such as criminalizing Indigenous practices, killing woolly dogs, and reducing women’s cultural roles, doomed the dogs to extinction, is equally as critical as genetic studies in understanding the deep history of Coast Salish woolly dogs in the Pacific Northwest.

The study also shows how previous researchers took too narrow, and often misinformed viewpoints, such as attributing the extirpation of woolly dogs to the introduction of non-Native blankets or the use of sheep’s wool. “Well, that's one way of looking at it, but I don't think that really would have been the case, because these are really cherished dogs to us and that it would have been more convenient or whatever, that doesn't really align with my understanding of our practices and our culture,” Stó꞉lō Elder Xweliqwiya Rena Point Bolton, who was 95 years old in 2022.

"I think the confirmation of these wooly dogs is exciting....As a descendent and a weaver I feel affirmed. Like it is not an accident that a wooly dog was preserved. The story and history needs to be told,” says Violet Elliott, Snuneymuxw First Nation Artist, who was consulted for this study.

I’d like to thank Audrey Lin and Ryan Lavery (Smithsonian), Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa, and Violet Elliott for this assistance and permission to use information they provided. I have not included a link to the Science paper because it wasn’t available when I wrote this newsletter.

So cool. Thanks for highlighting this collaborative research! There was an article (1920s) in the old natural history magazine Nature about them. That’s where I first learned about them.

This is fascinating! I always wondered about why the dogs would have gone extinct. Wouldn't it be possible to clone a wooly dog from existing DNA?