Trees die every day of every year but something unique happened late autumn or early spring 1,100 years ago. Numerous Douglas firs perished, not because of disease or fire, the two typical culprits of that era, but because of an earthquake, or quakes, one of the most noteworthy seismic events in recent Pacific Northwest history. Still extant, the dead trees, some more than several hundred years old when they died, occur at six locations across Puget Sound.

Death came to the Douglas fir trees in the following locations.

Price Lake - A quake-induced stream impoundment submerged a forest. Researchers sampled 21 trees, including several that required an underwater chainsaw, which sounds sort of nutty and fascinating.

Hamma Hamma - A rockslide dammed a creek forming a lake that killed a forest that the geologists found.

Dry Bed Lake - Yep, once again the earth shook, rocks trembled and fell, and created a temporary lake. Researchers were only able to collect these trees in a severe drought.

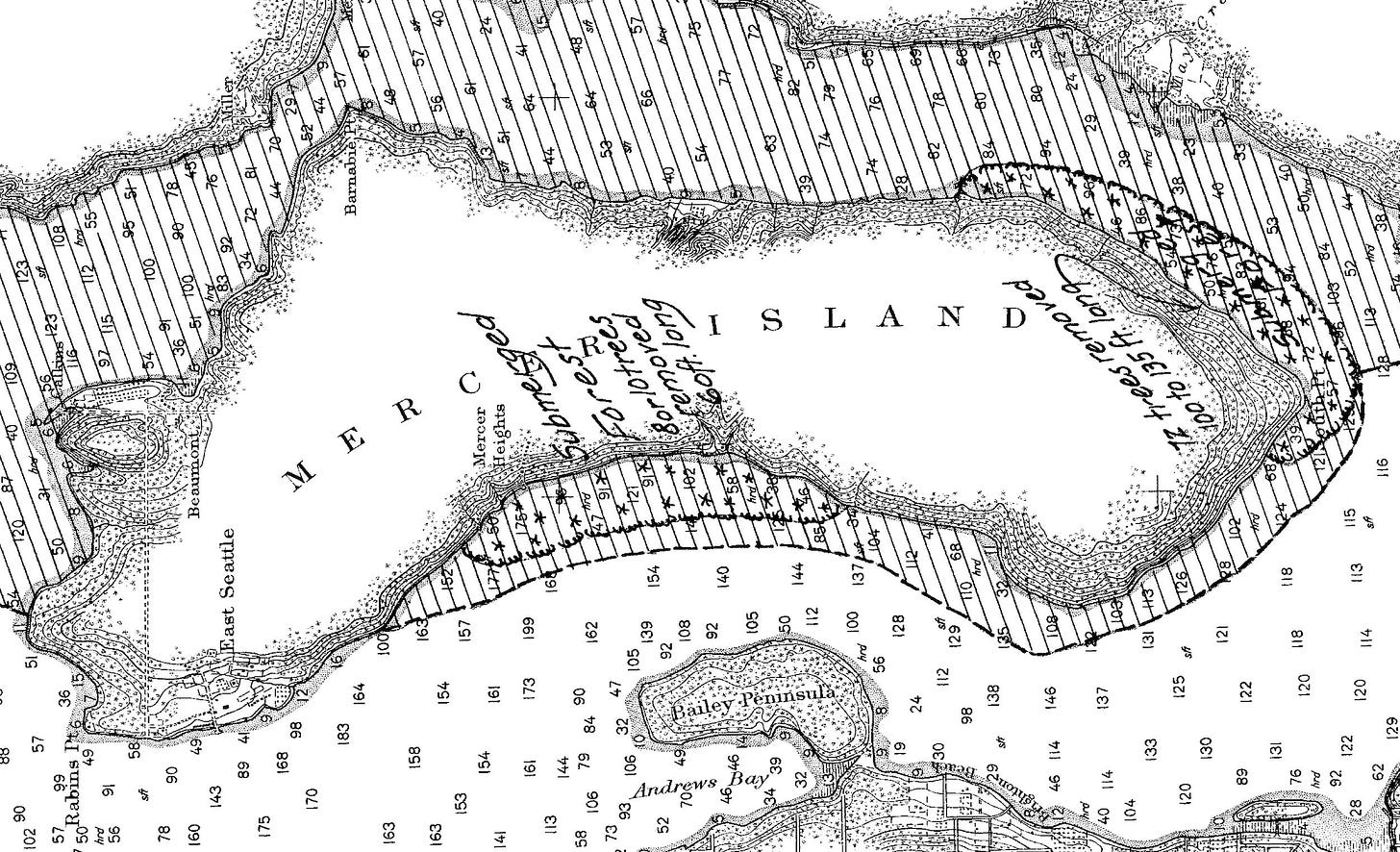

Lake Washington - This time an entire grove slid into the lake, off the SE end of Mercer Island. They are still there, standing upright. In 1916, the top of one tree pierced the 78-foot ferry Triton carrying 25 passengers. It sank but no one was hurt.

Lake Sammamish - Another grove, another landslide, more dead upright trees.

West Point - The ground snapped, trees died, and one was carried by a tsunami to a beach. This random event may have been witnessed by people who seasonally camped there to harvest shellfish. Lucky them.

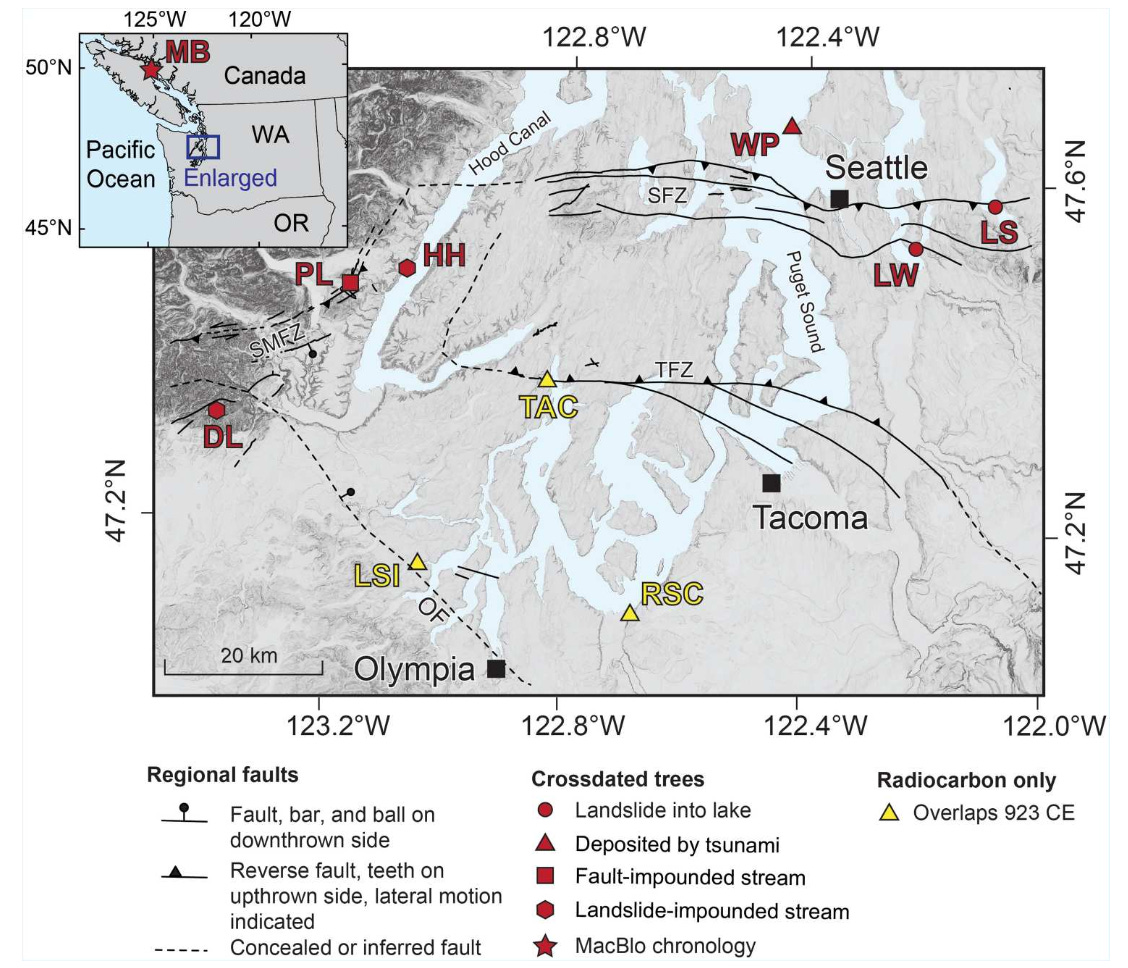

In December 1992, geologists published a series of papers with a startling conclusion: around 1,100 years a massive earthquake whacked the Seattle area, causing uplift of 23 feet. The quake occurred on what the scientists dubbed the Seattle Fault, a 25-mile zone of weakness running from Issaquah through downtown Seattle to the eastern edge of Bainbridge Island. (When you ride the Bainbridge Ferry, you pass by Restoration Point, thrust out of the water when the land shattered.) Relatively shallow, the quake measured about magnitude 7, not much stronger than the 2001 Nisqually earthquake but with much more significant ground shaking because it occurred closer to the surface. When (not if) a similar quake hits again, it will cause billions of dollars in damage.

One question that has longed challenged geologists is the specific date (more exact than “about 1100 years ago) of the quake, or quakes. The more details, such as timing, magnitude, and extant of damage, researchers have, the better they can model and predict future earthquakes and, they hope, help planners prepare for worst case scenarios. Geologists have known since 1992 that the best evidence for a precise date could be found in the annual growth rings of trees, which respond directly to climatic conditions preserving a detailed record of the history of a tree. They further knew that the quake created numerous geological events that killed or buried trees across the region. All the geologists had to do was locate trees, get samples, and read the evidence.

Last week, in a research article in Science Advances, an international team reported that they had solved the dating mystery, narrowing the date of the quake(s) to 923 or 924 CE. It is a tour de force and beautiful example of science, taking a unique set of features and combining technology with old school-out-in-the-field, mucky, muddy detective work to answer an essential question.

After the researchers gathered the trees, which they did over the past 30 years, often in less-than-ideal situations, they compared ring-width patterns. They also compared the trees with an absolutely dated reference set of 27 cores from Vancouver Island that spanned the years 715 to 1990. And, finally, they independently radiocarbon dated the samples. Everything pointed to 923/924 but what was surprising is that the researchers found that there may have been two quakes, one on the Seattle Fault and one on the Saddle Mountain Fault (near Lake Cushman and labeled in the map above as SMFZ), that acted as double-blow, rupturing the ground twice within hours to months.

This is not good news. We all know that one quake is bad. If a second quake struck shortly after, infrastructure and emergency planning, not to forget the landscape itself, would be vulnerable and prone to more catastrophic issues. But now that these scientists have provided the information on what did happen and what could happen, planners have the opportunity to help build in more resiliency. As my pal Scott says, “Get to work you.”

All too often in our modern world people question science and scientists, claiming that they have agendas or are only interested in making money from their research. Over the past 25 years I have interviewed dozens of scientists—in academia, government, and consulting—and have found all of them to be committed to doing the best work they can without any agenda or financial gain. This study certainly exemplifies the best of what scientists do: solve a mystery to help further our understanding of our world, often with the goal of making a better world.

Thanks to Pat Pringle and Brian Sherrod for their helpful comments on producing this story.

Yes! Thanks so much for digging into this. I saw the news brief in Science and was hoping for a bit more context. Such cool research. Have you or others written about the upright trees in Lakes WA and Sammamish and how the heck they are still upright after 1000+ years? Why wood lasts so long in certain underwater environments? Were all the trees in this study Doug firs?

David, thanks for that post which is equal parts fun, fascinating, inspiring, cool, and terrifying. I am wondering if you came across any science from further north or south along our Megafault that might indicate similar, concurrent, catastrophic shaking south to Oregon and California or north of Vancouver Island? In other words, when the next big one comes, how likely is it that it will hammer just the Puget Sound area versus an entire multi jurisdiction economic region on the West Coast? And should we be investing in underwater chainsaws?