City On a Hill

Prepositions of Place

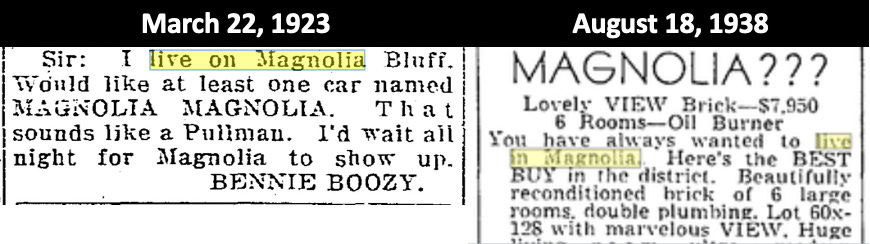

On a walk the other day, a woman asked me a curious question. Did I know how to tell if someone was a newcomer to the Magnolia neighborhood or a long time resident. (For non-Seattleites, Magnolia is a mostly tony neighborhood on a hill on the city’s west side.) “If they say ‘I live in Magnolia,’ they are a newbie. Old timers say ‘I live on Magnolia.’” I had never thought of this distinction so began asking friends how they described where they lived. Which preposition did they use when referencing their neighborhood? Was their place defined by in or on? (Of course, when I did this, I had one friend, a Magnolia resident of 50-plus years, who said she lived in Magnolia, and another, a recent resident, who said she lived on Magnolia, basically proving that you can’t trust everything you hear on a walk.)

Turns out, perhaps not surprisingly but not necessarily obviously that the difference depends on geography. For the most part, those who inhabit a definable landscape use the term on, as in on Capitol Hill, on Beacon Hill, on Mercer Island. Using in for these locations would sound odd. (I also wonder how much does the use of on reflect exclusiveness? We, the few, the proud, the special, live on a hill or an island and you off-island, elevation-challenged hoi polloi can only dream of our water-bathed or high elevation air. Or something silly like that!)

Those who don’t live in such places generally prefer in, as in in Licton Springs or in Laurelhurst. Seattle does have one topographically distinct neighborhood that defies this logic: Rainier Valley. Those who inhabit this anti-hill would never say on, as in on Rainier Valley. It’s always in Rainier Valley. These residents, like the hill dwellers, are acknowledging their local topography.

I suspect that most people, and I would include myself until my recent walk, do not make this topographic distinction consciously; they simply know that on or in sounds right without thinking about their prepositional preference. But, this choice is not solely dependent on geography. For instance, the neighborhoods of Queen Anne and West Seattle are each on a prominent hill, and few would say they live on West Seattle (though some people call West Seattle “the Island” and, when they do, they use on not in), whereas more residents would say on Queen Anne. (But as with the Magnolians, many on the Queen hill eschew this logic and say in Queen Anne.)

Then there are the more ambiguous hills, such as Crown or Sunset, where anything goes. It seems that if people are going to use on, they want their hill to stand out as a noticeable prominence and not merely an elevated location. I am thinking of places in Seattle such as View Ridge or Loyal Heights, names that feel more aspirational, or marketing-based, than originating with an obvious topographic high. My guess is that when using these location names that a majority tend to overlook the words’ specific meanings (that heights and ridge mean elevation and thus a hill of some kind) and instead simply focus on the name as a name, which has little meaning beyond categorizing a place. As so often happens with place names, they’re merely a moniker without meaning or connection.

Another favorite aspect of mine regarding our relationship to topography has to do with a change in how people refer to travel on, or is that in, Puget Sound. In contrast to how a modern person from Seattle would say they go down to Olympia and up to Everett, most early visitors and residents would have said the opposite, that they traveled up to Olympia and down to Everett. They were not directionally challenged. If you think about the land and water with a nautical mindset and not a geographic or automobile-based one, it makes sense. Sailing south into Puget Sound takes you toward the upper end of the waterway. You can also imagine Puget Sound as a river and the south end as the beginning of the watershed. Both lead one to think of traveling south as going up instead of down. By the way, an historian I know told me that old-timers he spoke to in the San Juan Islands fifty years ago, still used the anachronistic definitions of “up-Sound” and “down-Sound.”

I look forward to your thoughts on this subject. For instance, are there other geographic features that lend themselves to on versus in? What about for areas that are relatively flat; does no one use on in these locations? What about up Sound versus down Sound? And, don’t get me going on the misuse of the Puget Sound! ARRGH Though the Salish Sea is correct and I don’t know why?

I hear and appreciate consistent use of "on" in most land acknowledgements. Thoughtfully crafted, such statements lead us to consider both the place and a longer spans of time and stewardship of the land on which we live. Let us live thoughtfully, before we in our own time become ancestors dwelling both in the ground and in the air.

Geography aside, I get “in” line at the grocery store or wherever a waiting line exists. Many people get “on” such lines. I suppose a line can be geographic, such as a state line. A people line is sort of geographic, made up of people forming a line. But I wouldn’t stand “on” those people ordinarily, would I?