Here’s today’s unpleasant thought. “Two rats are probably having sex fairly close to you and three weeks from now, she will give birth to between eight and ten pups. This time next year, your fecund neighbors might have 15,000 descendents.” I wrote those lines in 2004, for the opening of a review of Robert Sullivan’s Rats: Observations on the History & Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants. Although those facts still disturb me, I thought I’d write about rats, as they seem an appropriate lead in to Halloween.

Like nearly every place on Earth, Seattle has its fair share of rats. They have probably been present in the city for as long as European settlers have been here. Taking advantage of our location on the water, rats would have traveled here by ship, particularly since our major trading partner for much of the late 1800s was San Francisco, a port that had a global trade network. When referring to rats in the urban environment, and to those who comprised some of the first wave of Californians to invade Seattle, I am, of course, writing about the black rat and Norway rat.

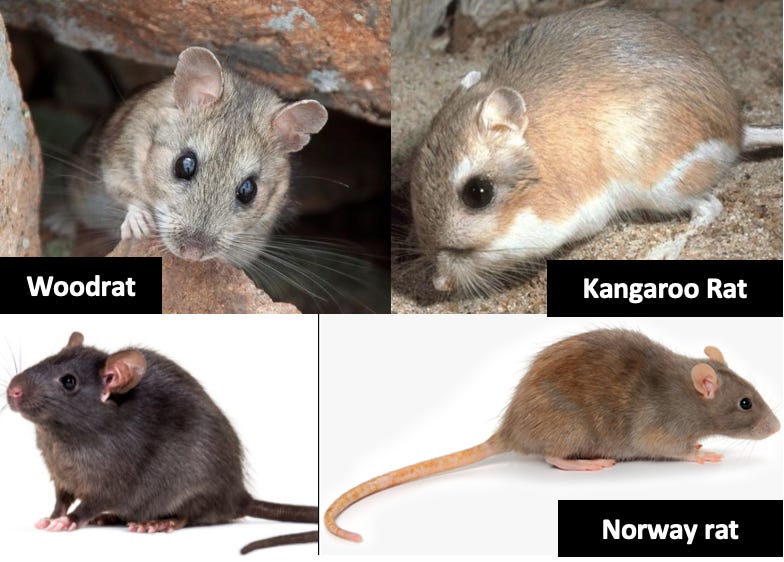

Both species evolved in Asia and have now spread world-wide. (Washington state’s native rats are the bushy-tailed woodrat and kangaroo rat though both are in different families than the black and the Norway and from each other.) Smaller, more slender, and endowed with a long tail, the black, or roof rat (Rattus rattus), is a strong climber more at home on ships than brown rats (Rattus norvegicus). Also known as Norway rats, because some misinformed biologist thought they originated there, R. norvegicus is more widely distributed, in part because they are more aggressive.

Rats began to achieve a measure of infamy in Seattle in 1908 with the city’s only outbreak of bubonic plague. Leong Sheng was the first confirmed plague victim, on October 19, 1907. He would have gotten the plague bacillus (Yersinia pestis) from fleas that lived on rats. Five days later, Agnes Osborne died, followed on October 30 by her sister Mary. The latter two had pnuemonic plague and not bubonic. Three others may also have had plague, though it was never confirmed: Agnes and Mary’s brother Ernst, whose policebeat was the neighborhood where Leong Sheng lived; their sister Lydia, who treated Ernst; and the mortician who prepared Ernst for burial.

In response, the city council passed two ordinances to try and reduce rat population. The first prohibited the dumping of various forms of garbage “detrimental to health,” including human excrement, dead animals, and butchers’ offal. (One has to wonder why it took an ordinance to stop people from such dumping.) The second focused on food storage and protecting buildings and is considered to be one of the first plague-derived, ratproofing ordinances in the United States. (Yet another reason to show some Seattle pride.) It led to the installation of 7,500 garbage cans, the death of 25,000 rats, and the placement of 128,800 pieces of rat poison in one year. Over the next six years, the city spent more than $50,000 on rat control including paying $16,369.20 in bounties at a dime per rat. Inspectors found at least 13 rats with plague bacilli.

A central reason for the abundance of rats was the condition of the waterfront, which was built on piles over tideland. Not only did early Seattleites like dumping disgusting things in public, they also liked to hide their sewage and garbage under the docks and trestles. Highlighting his fellow citizens’ proclivity to think that the tide would wash away their refuse, when all their efforts did was to create rat Nirvana, city health commissioner Dr. J. E. Crichton called for the construction of a seawall and dumping sediment behind it in order to remove the “cesspools of filth.” Eight years later, the city completed a seawall backed by fill between Washington and Madison Streets. Within a year, plague was no longer found in the city.

Rats are still an issue in Seattle, with news outlets periodically reporting that the city is one of the “rattiest” in the US. I know that we have had them in our basement and our attic. I also know that many people unknowingly create good rat habitat by allowing ivy to grow; rats must think we like them, providing a ground cover with lots of space for movement. Indeed, we seem to have gone out of our way to make our world hospitable for rats and they understand and appreciate it. As Templeton the rat tells Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web: “For your information, pig: The rat rules! We were here long before your kind and we'll be here long after. So, you just keep that in mind next time you feel like reducing me to just 'the rat'.”

Word of the Week - Cesspool - A well sunk to receive the soil from a water-closet. The OED notes an uncertain etymology. Cesspool may come from suspiral, or vent; from cistern; the Italian, cesso, a privy; the Latin sedēre, sessum in sense ‘to sink, settle down;’ or cess, a bog. The renowned philologist Prof. Walter William Skeat thought cesspool might derive from suss ‘hogwash’ or soss ‘anything dirty or muddy.’ But all these are merely suggestions, calling for further evidence, notes the OED.

UGH -rats! We recently had a rat issue due to the numerous bird feeders our neighbor had up next door. My dog was having a heyday watching for them and chasing them this summer. We also knew they were getting in under our house, as last year we could hear them inside and discovered a spot they may have been getting into the crawlspace. About the time the rat problem peaked this summer I was cutting back some plants and found that one of our foundation vent grills was entirely missing (the whole was big enough to let in anything from a mouse up to a possum or cat). We had words with the neighbors and they removed all of their bird feeders (except hummingbirds). Lo and behold without the food source, the rodents went away. The gaping hole was fixed just yesterday, so I can rest easy knowing that no critters will get under out house from that spot.

Thanks for the interesting read!