They say a pelican’s beak can hold more than her or his bellican. This may be true but first I want to write about their flight. On the wing, pelicans regularly switch between flying and floating, seemingly triggered by one bird, in a sort of follow-the-leader game. When she stops or starts flapping, the entire collective—known as a squadron, pod, pouch, or my favorite, a scoop—follows suite in an avian dance of wind-borne choreography.

Just south of Carmel, Point Lobos State Natural Reserve is my favorite spot to see pelican aerial virtuosity. One time I was fortunate to observe them doing something I didn’t expect, landing in trees to roost. Social birds, they were gathering in great scoops, dropping atop the Monterey cypress along the shore. For birds that one writer described as “very ungainly…and uncouth” on land, they settled onto their airy roosts with grace and precision.

Even more exciting is watching the big birds dive for a meal. Flying along, a bird suddenly veers, tucks his wings, corkscrews slightly to the left (to protect vital organs on his right side), and dives into the water, where he collects water and food in his gular pouch, the stretchable skin connecting lower mandible and neck. Pelican feeding is aided by their good eyesight, which around Carmel, centers on herring, at least when feeding.

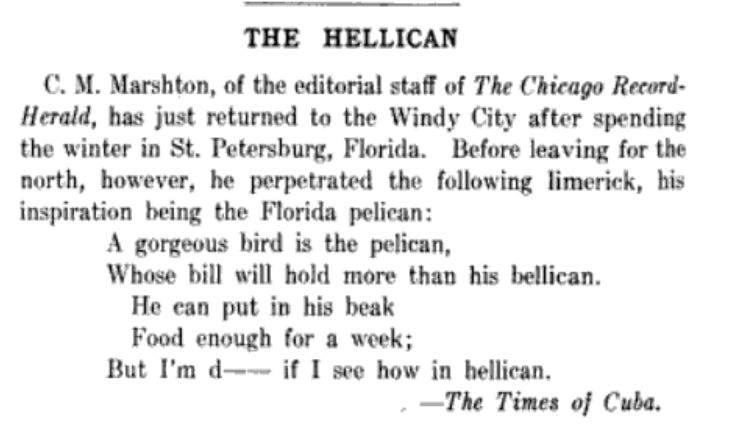

This behavior resulted in one of the more famous bird ditties of all time.

Often attributed to Ogden Nash, the poem may have been penned by C.M. Marshton, though he denied it. So did another newspaper editor and oft-cited penner of pelican prose, Dixon Lanier Merritt, though he preferred wondrous over gorgeous. What the limerick fails to note is that pelicans can suffer for their feeding method. When pelicans surface and drain their gular pouch, a gull or tern may arrive and steal the larger bird’s meal. While kleptoparasitising, the pirate either lands on the pelican’s head or back or dives in and nabs a fish. Oddly, pelicans have “never been observed to show anything but stoic calm during this procedure,” wrote one birder in 1946. More recent birders, in contrast, watched “a pelican seize a gull with its bill and toss the bird aside,” which seems for more likely and more interesting to see.

I have long enjoyed reading through older field guides and reports because they often contain comments such as “stoic calm” and “uncouth appearance.” Unfortunately, these writers also incorporated negative stereotypes and other insensitive anthropomorphisms. I am not opposed to anthropomorphism because it can help people better visualize and relate to a plant or animal but in many cases word choice reveals more about the authors than about what and who they are observing. As is always the case, be careful about the words you use, though I am quite forgiving of rhyming pelican, bellican, and hellican!

Word of the Week - Kleptoparasitism - A relatively new word for an ancient practice, kleptoparasitism first appeared in print in 1952 and refers to “parasitism in which a bird, insect, or other animal habitually steals prey or food-stores from members of another species,” according to the OED.

Was recently kayaking in the intercoastal waterway near Manasota Keys, FA, and had the exquisite pleasure of watching these Flying Wallendas quite near our crafts. Had a harm time resisting saying "Wham!" every time they hit the water. I was unaware of their need to corkscrew to the left. Will focus in the future on this feature Thanks

I love new words, or at least words I did not know!