I recently realized that forty years ago this month I took a class that changed my life. I didn’t know it at the time. Nor had I even planned on taking the class when I went to college. I had originally planned to get some sort of engineering degree as I hoped to design bicycles. But after getting a 16% on a three-hour quiz in physics, and struggling in calculus, I concluded I needed to reconsider my options. Fortunately, I had taken Intro to Geo prior to the physics classes and realized that I was much better at field trips (in physics our lone field trip was to a door to talk about momentum or inertia or something equally obscure). I had taken what would be my life-changing class at the suggestion of a geology major, who I had met on three-day bike ride to Aspen.

I still remember our first class field trip. We walked about a half mile from campus to a road cut, basically the geology world’s equivalent of seeing a cadaver; it was Anatomy 101 as we got to see under the skin of the earth into the tissues below. Our professor asked us to draw what we saw and label the different rock layers. I don’t remember what I drew but do remember him telling us that we needed to look beyond the colors and to notice the textures and the way different layers intersected. It was my first lesson in paying attention to the natural world.

I did eventually major in geology and was fortunate to spend a great deal of time on field trips traveling around the American Southwest. I still have rocks I collected (see below). One of the highlights was a week on a Structural Geology class in Arches National Park mapping the geology of Salt Valley. I certainly wouldn’t have predicted then that I would end up moving to Moab, Utah, five miles from the park, where geology became central to my existence. It impacted where I hiked, biked, and canoed and was a main topic of the programs I taught. Plus, I discovered that I liked knowing why the landscape I treasured looked like it did; this is still a central reason for my love of geology.

During my nine years in Moab, I worked as a park ranger at Arches for three seasons. (When I graduated from my college my mom said to me. “I read all of your report cards and you never shut up in school.” I subsequently read those reports and they tended to include the line, “David is a good student but he disturbs the other students with his talking.” As a NPS ranger, I was finally getting paid to talk and disturb the visitors! You, too, can experience my non-stop talking on one of my guided walks, which will probably ramp up again in spring.)

My other job in Moab was working with a small, non-profit educational field school. It was an amazing group of people—staff, participants, and instructors—who were deeply interested in all aspect of the natural world, from bugs to flowers to birds. Out in the field with this gang, they helped me broaden my understanding of nature, moving me beyond my narrow geocentric view toward one that still guides me today, looking for connections between plants, animals, rocks, and humanity. It was exciting to see how junipers thrived on a particular rock layer; how black widow spiders exploited the many cracks in sandstone; how relict Douglas firs had survived since the last Ice Age in a north facing alcove; or how Cooper’s Hawks made their nests in cottonwoods that had tapped into a seep. The influence of geology could be seen everywhere, tying together the landscape into a complex quilt of life.

I still see the world through a geologic lens. When my wife and I left Moab and moved to Boston, one of the great solaces I found was looking at the geology of the city’s building stones. That interest was essential to helping ground me in the city and to finding the connections to place that are so important to me. In my 25-plus years back in Seattle, I have continued to seek out the geologic stories of the city and its surroundings. I revel in how the region’s geologic past influences where I ride my bike, the trails I hike, and the potential disruption (earthquakes, landslides, and volcanoes) that will come to pass. (And, then there’s how geology influences world politics but I won’t head down that path.)

I certainly did not expect to develop this life-long interest when I took that Intro to Geology class in college. I have no idea who the guy was on the bike ride who suggested that I do so but I am glad I listened and made the discovery between the deep past and my long term joy in life. It’s a connection that I treasure every day.

Thanks kindly for indulging my trip down memory lane.

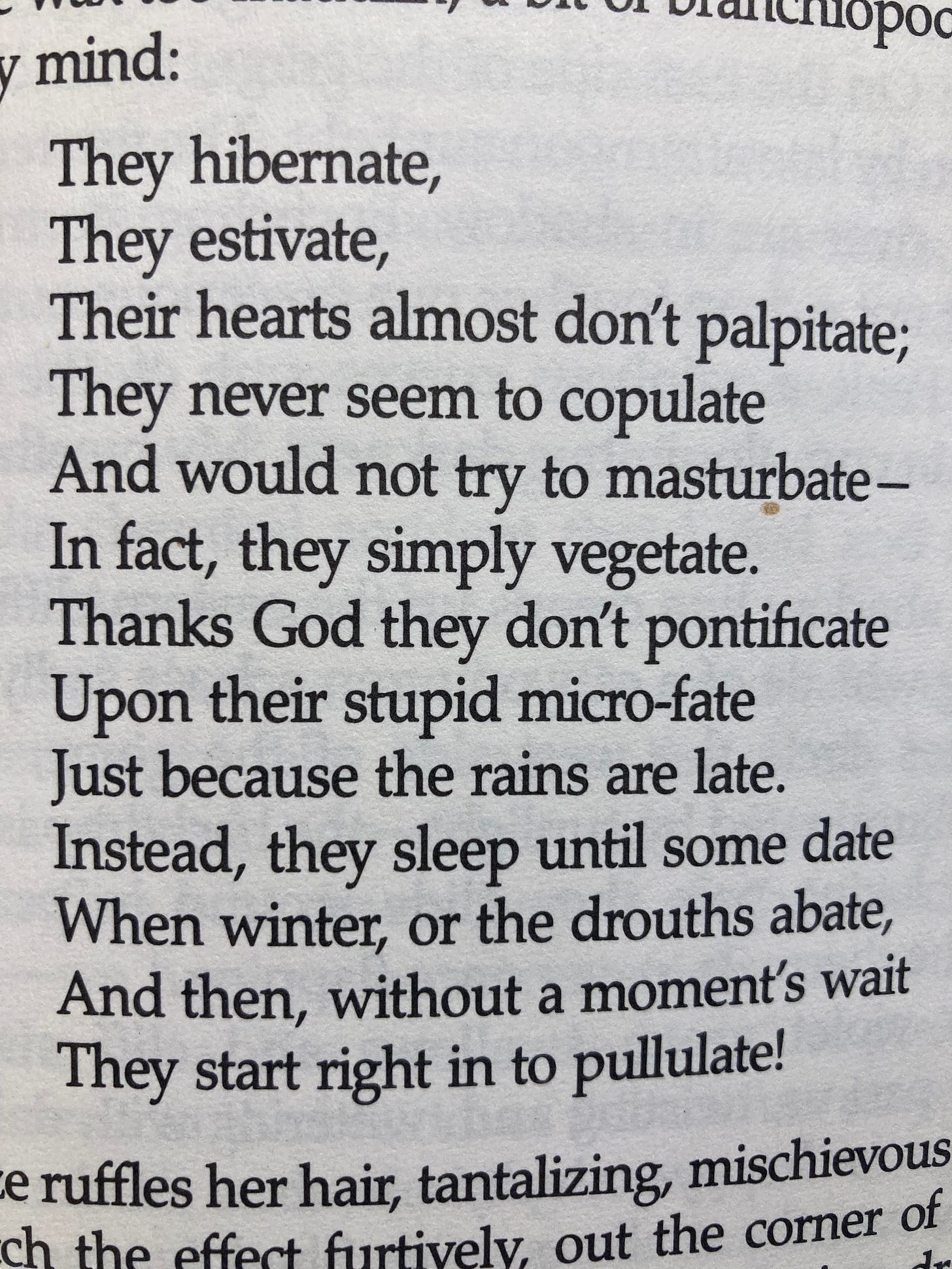

Sad to read of the death of John Nichols. Most familiar as the author of The Milagro Beanfield War, he was a writer grounded in place, honesty, and justice. I have long been tickled by this tribute to fairy shrimp, which comes from one of my favorites of his, On the Mesa. I once met him (well he walked by me before kicking my friend by accident in the foot) at a party in Taos. He was dressed in an old beat up parka and looked a bit uncouth, which was so great. “Hey writers dress like me,” I thought.

Two people have now commented on pullulate, which means to multiply rapidly. It comes from the classical Latin pullulāre to send forth new growth, to sprout, to sprout out, spring forth. So now you know.

Great to find your Substack! I had not heard about Nichols’ passing. One of my favorite writers in college. Memories of a March spring break ski trip into the Pasayten reading MBW aloud by flashlight while wolves howled and lynx padded silently by.

And thanks for sharing the ode to fairy shrimp!