Botanists recently discovered a new and deadly plant, at least if you are a small bug. Found in bogs and other sunny, wet, and infertile locations, Triantha occidentalis (known as false asphodel) does not look like the stereotypical carnivorous plant, such as a Venus fly-trap or sundew, with an obvious bug-luring body part. Instead, the plants rely on relatively inconspicuous glandular hairs to trap their meals.

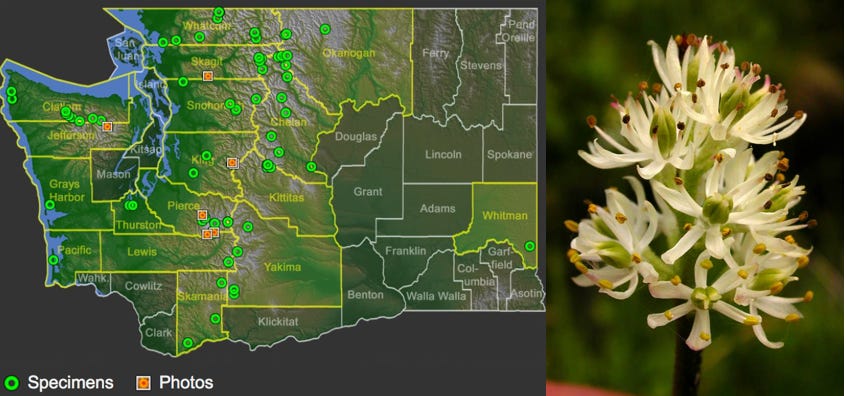

Although false asphodel grows near west coast cities (specimens in the UW Herbarium come from Snoqualmie and Stevens Passes), no one had thought to investigate the plant’s predilection for meat until researchers discovered that it lacked a gene often found in other carnivorous plants. When they looked at live plants, as well as herbarium specimens, they found fly and beetle corpses stuck to the plant’s red hairs. A deeper study revealed that the plants produce a digestive enzyme called phosphatase, which helps the plants obtain nutrients from their six-legged snacks.

The always amazing observer Charles Darwin was one of the earliest to write about carnivorous plants. In his Insectivorous Plants he wrote that the Venus fly-trap “was one of the most wonderful [plants] in the world.” As usual, he was correct; research has revealed that the plant’s doomsday snap trap is one of the fastest movements in the plant kingdom. At present, there are about 800 carnivorous plants, or about .2 percent of all angiosperms.

Part of what makes the false asphodel interesting is that the insect trapping hairs grow very close to the flower. In contrast, most carnivores of the plant world take the opposite approach as it’s generally considered a poor evolutionary plan to kill and eat those who are helping you to reproduce. Triantha occidentalis appears to get around this problem by having only enough stickiness to trap smaller insects. Big bugs, such as butterflies and bees, which tend to be pollinators, are powerful enough to not be trapped, so sticky, bug-trapping hairs next to one’s sexual parts doesn’t seem to be problematic for this newest member of the carnivorous plant clan.

Coincidentally, the Triantha’s common name, false asphodel, has an ancient connection with death. Homer refers to the “asphodel meadow” of Hades, a place described by some as “dark, gloomy, and mirthless” though others refer to the meadow as a paradise, fragrant and flowery. No matter one’s interpretation of the “asphodel meadow,” perhaps we should be more cognizant of the fact that some plants whose traits modern science has only recently recognized have attributes long known by more careful observers. Such is certainly the situation with Indigenous knowledge, which many scientists are finally coming to acknowledge as a source for keen insights based on long term observations and relationships.

In case you are interested, I will be leading a bookclub discussion for Third Place Books and KCTS 9 about a wonderfully splendid book, Letters from Yellowstone by Diane Smith. An epistolary novel about science, nature, exploration, and humanity in 1898, it is thoughtful and beautifully written, and stars a botanist. Please join me. It’s free. August 18, 7pm, virtual.

I love that we are still learning (or in the case of re-learning Indigenous knowledge) new things about the natural world!