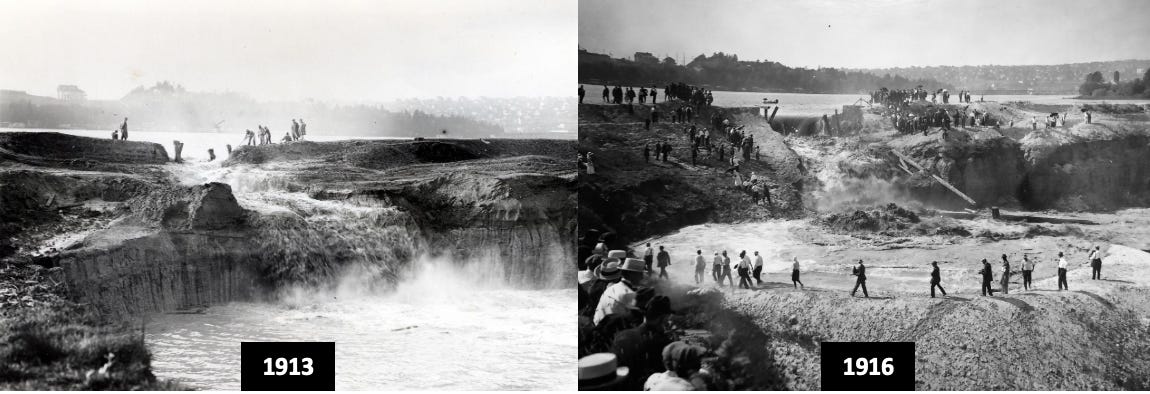

Two of the most famous historic photographs of Seattle detail landscape change. Taken three years apart from the same location—looking west from the south side of the west end of the Montlake Cut—both show the destruction of a cofferdam. If you have spent much time in Seattle, you won’t be surprised to learn that there were some unexpected difficulties with the geologic substrate, which led to delays in a massive urban project. For those who aren’t aware, I have one name for you: Bertha.

The story of the modern Montlake Cut begins in June 1912 with building a cofferdam at the west end. Using two steam shovels, two hydraulic giants, and a dipper dredge, the Stillwell Brothers Construction Company then excavated a channel 2,200 feet long and 100 feet wide at the bottom and an even 36 feet deep from Lake Washington to Lake Union. Stillwell used the sediment to fill nearby shoreline owned by the University of Washington. At the eastern end of the cut were control gates, which would be opened to let water out of Lake Washington when it needed to be lowered.

While excavating, Stillwell had had to contend with regular slumping on the south side of the cut. They hoped that when the cut was complete the weight of water would stop the slides. On December 31, 1913, they dynamited the cofferdam and let water from Lake Union fill the canal. Everything was great except for one problem, the south side continued slumping. So, Stillwell built a new cofferdam, pumped out the water, and concreted the south side. In November 1914, they had the pleasure of blasting the second cofferdam. Everything was great except for one problem, the north side now slumped.

This time everyone decided to show some patience. In April 1916, a new contractor started to build a third cofferdam, pump out the water, and concrete the north side. On August 25, workmen opened a small cut in the cofferdam then “sprang aside just in time to escape the inflow of water.” In exactly 56 minutes, 45 million gallons of water from Lake Union filled the cut.

I don’t know if any of you deal with safety issues. Even if you are like me and live on the cutting edge of danger, it is hard to look at this image and wonder what they were thinking: The goal of the day was to have the cofferdam wash away. An unnamed Seattle P-I reporter wrote: “Lieut. Col. John B. Cavanaugh…had no comment to make except to express concern for the lives of the foolhardy persons who ventured into the cut…In ten minutes the crowds on the cofferdam fled to escape being plunged into a raging torrent.” I am pleased, and surprised, that no one was injured, drowned, or died.

Three days later, gates at the eastern end of the Montlake cut were opened, allowing Lake Washington to be lowered by nine feet. Two to three months later—there is no official date for this event, nor was it reported in the newspapers—the lake reached its new elevation equal to Lake Union, the Fremont Cut, and Salmon Bay. Only 53 years from conception (the first mention of such a canal was on July 4, 1854) to completion, the Ship Canal officially opened on July 4, 1917.

If you can, it’d be a pleasure to see you on Saturday, November 19, at the Phinney Center building for the 13th Holiday Bookfest. It runs from 2 to 4 pm and has a splendid gathering of writers (me included), who will be on hand to sign their books. There will also be readings (me included) and food.