On November 13, 1851, twenty-two people landed on a low, open prominence of land jutting into Puget Sound. They named the spot Alki, soon also to be called New York. (I have long been tickled by the audacity of early Seattleites: New York, what were they thinking?) The Denny Party, as the arrivals are known, are generally considered to be the founders of Seattle. Though most of the original settlers abandoned the location, Alki is the most sacred spot tied to Seattle’s origin. But the Denny contingent were not the first Europeans to land there, nor the first to examine it as a possible place to establish a community.

On July 9, 1833, William Fraser Tolmie, a doctor and passionate botanist (he knew John Scouler) working for the Hudson’s Bay Company, visited the prominence. The HBC had established its initial base—Fort Nisqually—in Puget Sound just a few months earlier, about 12 miles east of modern day Olympia and, Tolmie had been sent to see if he could find a good location for another trading post/fort. Traveling by canoe, having set out at 9pm from Nisqually, he “courted the approach of the drowsy God but getting into a pleasing train of thought, about friends & native land soon lost the inclination,” or so he wrote in his journal.

Tolmie liked what he saw at Alki except for one small problem. “A Fort well garrisoned would answer well as a trading post on the prairie where we stood—it would have the advantage of a fine prospect down the Sound, & of proximity to the Indians, but these would compensate for an unproductive soil & the inconvenience of going at least 1/2 a mile for a supply of water.” This doesn’t seem terribly far to me, especially considering that Tolmie was a pretty serious explorer and later that summer spent ten days botanizing around Mt. Rainier, “whose gelid vesture it was most refreshing to behold,” he wrote.

But the half mile walk for water was just too darned far so, after a breakfast of “parboiled pease eaten with a shell out of a pot lid,” he and his Native guides left. Regarding the shell he mentions, I assume it means that he used some sort of clam or mussel as a spoon. Any thoughts? He also regularly mentions pease in his journal; seems some sort of legume infatuation to me.

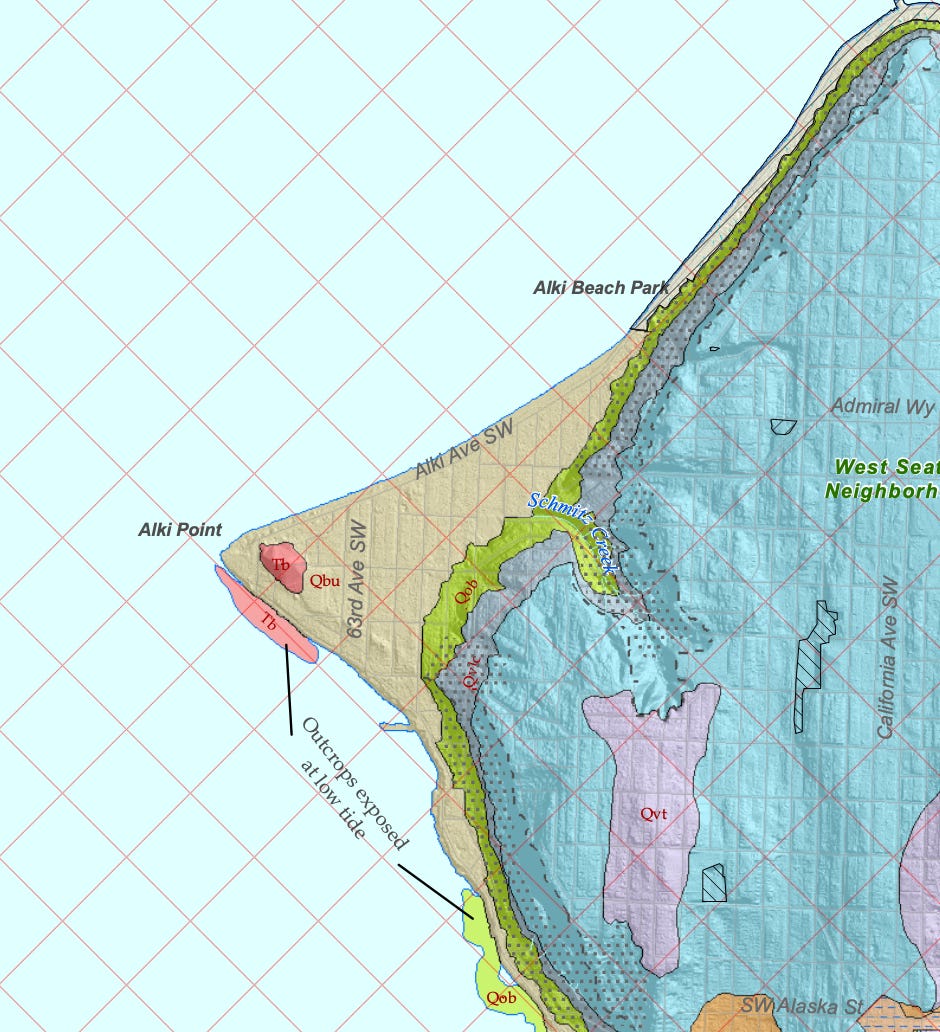

Alki lacks a freshwater source because it has been uplifted by the Seattle Fault, the east-west trending zone of weakness that periodically ruptures and produces earthquakes. In pushing the point above sea level, uplift formed a relatively level platform that extends west 1/2 mile from the bluffs, which is problematic because springs and seeps in the bluffs would have been the HBC’s source of freshwater. In the land south of Alki, where the shoreline is much closer to the bluff, access to freshwater is easier. But the platform also has assets; being flat and close to sea level, it was an attractive location for early travelers such as Tolmie and the Denny Party to land. If the platform didn’t exist, who knows how Seattle, or a not-Seattle, might have developed.

Despite being an avowed botanist, Tolmie didn’t mention any of the plants he saw at Alki. This is unfortunate because the raised bench was an unusual habitat, more prairie than forest, as reflected by the Native name for the spot, sbaqwábaqs, or Prairie Point. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, botanists did collect plants from Alki, 58 native species of which made it into the University of Washington herbarium. They include such splendid flowers as rose-colored Hooker's onion (Allium acuminatum), golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta), white prairie star (Lithophragma parviflorum), and violet harvest lily (Brodiaea coronaria). None of these plants now grows in Seattle and of the original 58, an additional 19 have been extirpated and 16 more are considered rare or uncommon.

One of the persistent debates in Seattle, if we are getting perjinkity, is the pronunciation of the word Alki, a Chinook Jargon term meaning by and by. The term appears to have originated with settler Charles Terry of the Denny Party. An ambitious man—he’s the fellow that initially named the area New York—he opened a store, the New York Markook House, on the point. Markook is a Chinook Jargon term meaning trade. Like the other original settlers, Terry, too, would abandon the peninsula (and the name New York, which he changed to Alki in 1853) and move to the new town of Seattle.

Nearly every modern day person who says Alki, pronounces it Al-kye. Terry and others of his era, in contrast, would have said Al-kee. As someone who has a proclivity to mispronounce words in any language I have encountered, I bounce back and forth between Al-kye and Al-kee. If I remember correctly, several years ago I gave a talk at MOHAI and went with the old timer Al-kee, figuring it might sound like I knew what I was talking about. After the discussion, a descendent of the Denny family got up and thanked me for my pronunciation. Later in the Q&A a more recent resident said “Well, that’s nice but we modern people say Al-kye.” It was all I could do to prevent a melee (take your pick on how you want to pronounce it, may-lay, may-lay, or muh-lay) between the pronouncers.

I don’t know if it happened but guess that it did, based on his long career (he was a central figure at Ft. Nisqually between 1833 and 1859), that Tolmie most likely passed by his water-deprived prairie after the arrival of the Denny party. Did he think they were wrong for settling there or respect their tenacity and drive? Did he ever notice the flowers? More importantly, how did he, a man who I assume had a wonderful Scottish accent, pronounce Alki?

Word of the Week - Perjink - A word of Scottish origins from the early 1800s meaning “exact, precise, extremely accurate. Also: fussy, fastidious, prim; neat.” You say persnickety, I say perjinkity. By the way, the original Scottish is pernickety, without the “s.”

A standard breakfast for the 49th NWSurvey team was bean soup. The cook would soak/cook the beans overnight in a cast iron kettle on the fire and they would eat it for breakfast . Not sure what kind of bean but one member of the team Harris, I think, wrote that one morning the black beans were served with a new vinaigrette which caused him much discomfort and weight loss for a week. Maybe pease were beans?

Pease porridge (hot or cold), made from peas, a pulse, was and is a common dish throughout the British Isles. Easily made with cheap ingredients and easily transported. One can imagine that dried peas, nutritious and filling, were a good thing to carry along on treks, easily reconstituted with water and eaten with a clam shell.